The Mailer Review/Volume 3, 2009/Mailer, Maidstone, and Me

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 3 Number 1 • 2009 • Beyond Fiction | » |

Daniel Kramer

Abstract: A photographer and film director for over five decades, Daniel Kramer writes about his experiences as a still photographer on the set of Maidstone (1970); included are a number of photographs taken on the set.

Note: © Daniel Kramer

URL: https://prmlr.us/mr03kra

In mid-July 1968 Norman Mailer went out to the eastern end of Long Island with a cast and crew to film a feature length film he called Maidstone, Norman’s big effort to make a movie that would blur the line between fiction and reality. There would be no script—only the one in his mind’s eye. Actors were given roles to play but did not necessarily know at the outset where their characters were going and did not know the resolution of the film, but did know their actions and dialog would provide the eventual script. When Look magazine sent me out to the set to photograph the making of Maidstone, I certainly didn’t know I would play an important role in the film, an un-cast character listed in the film credits only as “Man.” And I may possibly have saved Norman’s life.

This happened forty years ago. The events on the last day of shooting, I always thought, were personal and should stay that way. When Phillip Sipiora asked me to contribute a piece about Norman and film for The Mailer Review, I did my very best to get out of it, but Phil is a persistent editor and he won out.

I first met Norman in 1967, around the time I finished a year-long book project photographing and writing about Bob Dylan during the time he changed from Folk to Rock and greatly influenced the world of music. I had some telephone conversations with Norman in the summer about wanting to make a series of photographs of him while he and Beverly and the children were still in Provincetown before closing their house for the season. So, in September, I drove to Massachusetts without any particular arrangement with Norman or a very definite plan of my own about the pictures except, as I told him, “it’s for history.”

On the back deck of his beautiful white clapboard house, Norman and I looked out at the water and talked about the pictures we would make. I explained that a series of pictures, especially if they encompass work and play and family, could form a kind of three-dimensional portrait, and he agreed. The most memorable part of our first evening, after dinner with Norman and Beverly at a local restaurant, occurred some time after midnight and a few scotches later when Norman decided that if Beverly and I would be his audience he would (standing in the middle of the living room) read to us from Why Are We In Vietnam? I think that his performance ended about first light.

I spent the next few days photographing. Between Norman and his activities and Beverly and the kids there was quite a bit to cover. One of the things hard not to notice during this time was the ever-present sparing going on between Norman and his summer intern, or with Beverly, and sometimes even with the children just for fun. Widely known was Norman’s interest in boxing and his own training in the sport with former light heavyweight champion Jose Torres. Also, often present, was some sort of Mailer challenge for anyone willing to give it a try—such as the tightrope stretched across the back deck of the house. I must say that Norman did fairly well with it. I decided to keep my feet on the deck.

The next time we got together for making pictures was on the set of Beyond The Law. Norman was filming a police drama in the close quarters of a stationhouse setting and I got to meet and photograph some of the cast who would later also be involved with Maidstone—Rip Torn, Buzz Farber and cinematographers D.A. Pennebaker and Jan Welt. Beyond The Law was my first encounter with Norman’s concept of making a film without a script, juggling fantasy and reality. Actors and would-be actors and some not-so-would-be actors were given identities by Norman and very little else in the way of direction—just some idea of where they were going—or generally what was expected of them. Having recently just became a member of the Directors Guild of America, I found it all very interesting to be involved with Norman’s “method” of film making.

Sometime after the Beyond The Law shoot, Look magazine became interested in running my pictures of Norman and thought they should build a piece around the upcoming Maidstone project. I went out to the film set with Look’s senior writer Joe Roddy. Norman brought his band of players and camera crews and production people to some very beautiful locations in the Hamptons. If he was on target he could set the stage, turn his actors loose with their outline, give instructions to roll the cameras and, if all of this was balanced just right, it would yield a kind of existential experience and turn make-believe into cinematic reality. The sense of mystery about the full story line helped create a tension during the shoot that was also fanned by Norman’s own behavior, including his boxing on the set and plenty of alcohol and sexual themes in the film that spilled out here and there.

In the end, Maidstone may or may not have been the success Norman hoped for it, but he certainly had earned the right to try, and he used his own money down to the bone to make it happen. I was with him one evening in, I believe, a dining room in one of the homes that he used for a location when, after a long day of shooting, an actor complained about how Norman was mishandling the shoot in general and his part in the film specifically. Norman responded by telling him to get his own $250,000 and make a film the way he thinks it should be done. The fellow replied with what I recall was—“well you can take your script, roll it up and shove it up your ass”—a bad choice for a line with Norman who instantly followed with a right hand punch that broke the guy’s jaw. After he returned from the hospital with his wired jaw, I saw Norman write him a check for what I believe was $20,000—all part of the weave and fabric of Maidstone.

Norman played Norman T. Kingsley, a great film director about to possibly make a run for the presidency, and Rip Torn, a real actor’s actor on this set, played his half-brother Raoul, who was to assassinate Kingsley and bring about the film’s conclusion. There are many stories as to how all of this was or wasn’t planned or what Norman ultimately knew or didn’t know about the “event” that was to end the film. What everyone now knows is that the two men did in fact have a major brawl on peaceful Gardiners Island that included a hammer and blood, that’s in the film, and that this infamous ending was shot by the film crew a day after the official filming was completed. I saw what happened through my viewfinder and photographed it.

Gardiners Island is a unique place, owned by the Gardiner family for hundreds of years, and originally given to Lion Gardiner by the king of England. Our host, Robert Gardiner gave Norman carte blanche to use the island for one of his locations and had personally taken us for a tour of the island. In looking through my contact sheets of that day, I see Norman, Beverly and the children were out for a long walk in the fields and exploring an old windmill. Beverly’s flowing long white cotton dress added a sense of a much earlier time to the scene. It was really a very nice moment, a large open space, serene, pastoral and there were birds. I made one of my best pictures of the family that day, the six of them from behind, walking in this fairytale set- ting. It’s a picture Norman also liked and it ran as a double page in Look and was later widely published.

I don’t quite remember how it came about that Norman separated himself from the family. Maybe he was preparing for an encounter with Raoul. When he moved to an area near a large tree that sloped up to higher ground he was suddenly approached by Rip Torn, as Raoul, who sprang up into the air in order to swing a hammer above Norman’s head and strike him hard. It was a real hammer, not a toy one as has been reported. Although a bit lighter than a standard sixteen-ounce hammer, it had a wood handle and a solid metal business end. The sound of the metal on the bone was quite loud and startling. The assassination was on!

It was hard to believe what I was seeing and hearing. It certainly didn’t seem like a movie stunt but like a real moment (maybe it was), yet being on a film set, how can one be sure? Maybe the blood that started down the side of Norman’s face wasn’t real (or maybe it was). Norman backed up and yelled at Rip to stop but Torn (as Raoul) kept charging forward and brought the hammer down again. In desperation, and in an effort to defend himself, Norman charged at Rip, wrestled him to the ground and the hammer was lost in the exchange. In retrospect it surprises me that Norman who had been sparing almost daily on the set with his coach, Jose Torres, the same Norman who just a day or so ago broke a man’s jaw with a single punch, decided to grapple Rip to the ground and bite his ear half off instead of taking the stance of the boxer and play to his strengths and advantage.

Norman never really had the advantage on the ground. Torn seemed stronger and was faster and soon had the better of the situation. With both hands on Mailer’s throat, he was throttling him. Norman wasn’t speaking or yelling anymore—he was moaning and wincing—his air was being cut off. Was this real or was this theatre? The film cameras were still rolling. What did Pennebaker know? They kept shooting. Were they in on it? Was this a setup? If the fight were interrupted, would it destroy the most important moment in the movie—the assassination attempt?

The fight had escalated to a danger zone. Even between friends, no matter how it starts or what is said, if combat continues and escalates to a meltdown point, each combatant begins to fear that the other can inflict terrible harm—and this becomes a license to defend and do whatever is necessary to prevail, necessary to survive. However the fight may have started, whatever the impetus, fantasy had in fact morphed to reality on the set of Maidstone and the whole exercise of blurring the line between truth and fiction had actually come to a focus. There it was.

Being on a set for a week where no one really knew the outcome of any scene, I wondered if all this was playing out for the film and shouldn’t be interrupted. Pennebaker continued rolling, and his sound crew stayed with the action from the beginning while I kept shooting stills. With the hammer out of the scene, I felt it was basically a tussle. Then suddenly Norman broke momentarily from Rip’s hold but not fast enough to change the situation. Rip, seizing the opportunity, got his right arm under Norman’s throat, rolled on top of his back and locked him into a very secure chokehold. That was very bad. Chokeholds can kill.

While all this was happening, I had my own concerns. What if Norman is in real danger? When do I act? When do I alter the moment? Interfere? It was an old dilemma. When should a journalist not just cover an event but become part of it. I got the message when Norman’s face started turning purplish—a color I had seen many times working summers as a New York City lifeguard during my college days. I knew I would have to rescue someone who was not getting air. Looking back, I realize I was about to do the thing Norman had played with all through his film, putting people into character to see what would happen. In my case, it was reversed. Not only did my own character enter whole into the film, my role was also unscripted like the other actors but mine was completely unsolicited.

I stripped off my several cameras and tossed them aside. Beverly, suddenly aware of what was happening, came screaming into the scene doing her best to swat Rip Torn and pull the two men apart. Rip still had the chokehold. One of the actors still in the area rushed in and pulled at the two men, but Rip was strong and his arms wouldn’t unlock. No longer the journalist, I knew I had to do the unthinkable and go through the fourth wall, instinctively knowing that time was of the essence. I ran to help Beverly and the actor, who were still trying to get the combatants apart, and I was able to move Norman’s arm away from covering Rip Torn’s grip. He had very little strength left and his arm came away easily. Then I went for Rip’s hand, which was tightly locked to his other arm and pried his thumb away from his grip, twisted it and pressed it to the back of his hand, a technique designed to create considerable pain. Rip opened his hand, and I was able to grab and twist his palm and turn it out causing him to loosen his hold on Norman. There was no director to yell cut on this scene because the director had been unavoidably occupied and could barely breathe. That’s when I announced to both men that “it was over” in the hope this would give them space to get past the moment. Then I went looking for my cameras.

It is possible that if Rip had continued his hold, Norman could have suffocated, even accidentally. Once separated, the two men continued their aggression but only with harsh words, as neither wanted to go back into the fray. With camera still rolling, Rip chided Norman that without this assassination scene, he wouldn’t have a film. As they walked apart in a slow dis- engagement, they condemned each other—saving face, dueling egos or performing for the camera to save a film, I’ll never know. Finally, Norman, banished Rip and told Pennebaker to stop shooting. With Norman, Beverly and the frightened children, I went back to the main house to clean the wound in Norman’s scalp, draw the skin together and close it with butterfly stitches. I was told that Torn was treated at the hospital for an infected ear.

Exactly as Rip predicted, Norman did need the assassination attempt in the film. The entire fight scene made it into the final cut—including the rescue. Norman never complained to me that I entered his movie, or took the action I did, but he did complain about and questioned why some others did not jump in. In reviewing my contact sheets (like the photographer in Blow Up), I have come to believe that Norman and Rip had planned a moment of confrontation for the camera, but Norman never expected the hammer—certainly not the hammer blows to his head with his children nearby. It just all got out of hand.

In the five decades that I’ve been a professional photographer, I’ve had the immense pleasure and privilege to meet and work with some extraordinary people. I count Norman, Beverly and Rip Torn among them. I still go out of my way to see a Rip Torn performance, and I’m sorry that I didn’t get to know him better. Norman was very giving—always open with me. I know that I took away something good by knowing him. In rereading some of his letters to me I recalled another evening in Provincetown with Norman, my wife and Beverly. Norman inscribed a copy of [[The Armies of the Night]—“To Dan and Arline while eating at Ciro and Sal’s and improvising Wild 90 Revisited” and then below “Cheers, Norman—Sept 1968” he drew a lens and a camera cable release. I wish that I could recall what we were all doing in that restaurant that night that caused us to improvise his first film. I miss his being around.

I sometimes ask people I photograph to teach me one particular thing. Joe Frazier showed me how to throw a left hook. Bob Dylan showed me how to place the harmonica for a certain effect he makes. When discussing writing with Norman, I confessed my disappointment that as a high school student I won only 200th place out of a possible 200 in a Writer’s Digest short story competition. He cheered me by saying that as many as ten thousand people may have submitted stories! I asked him for a quick writing lesson. “Leave out the bullshit” he said. I think that this would be a good place to stop.

-

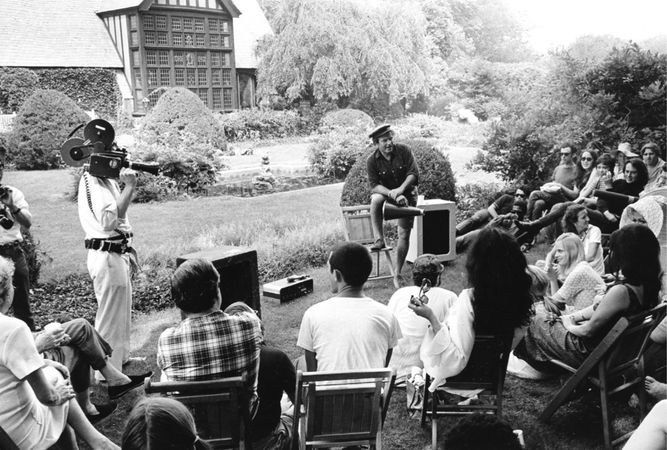

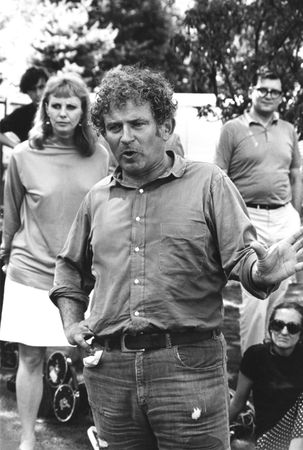

Norman Mailer directing cameraman Pennebaker on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer and Cast on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

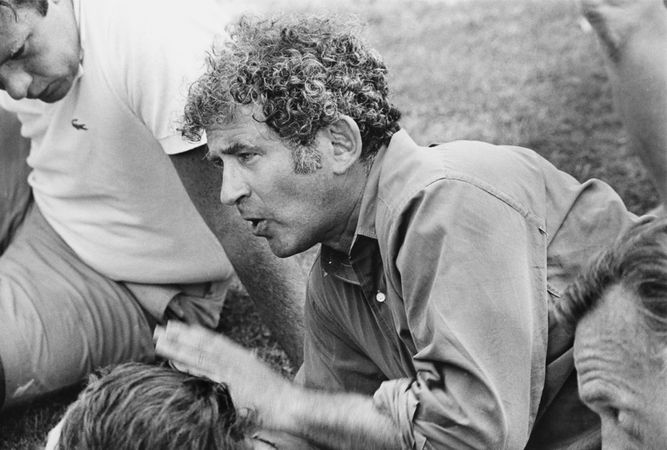

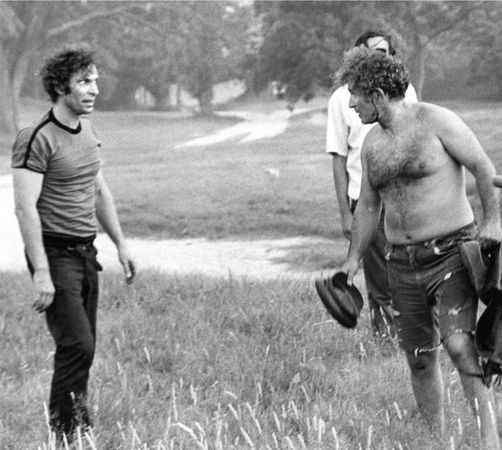

Norman Mailer on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer directing scene on set of Maidstone, Long Island, 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer directing a scene on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

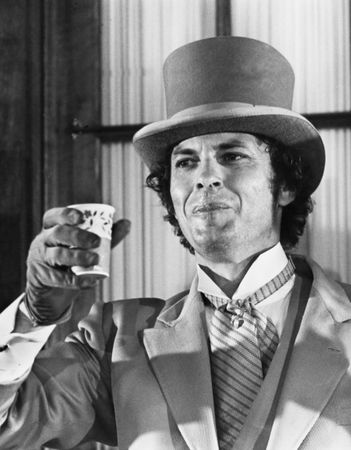

Rip Torn on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

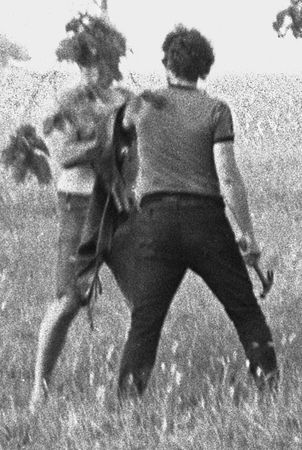

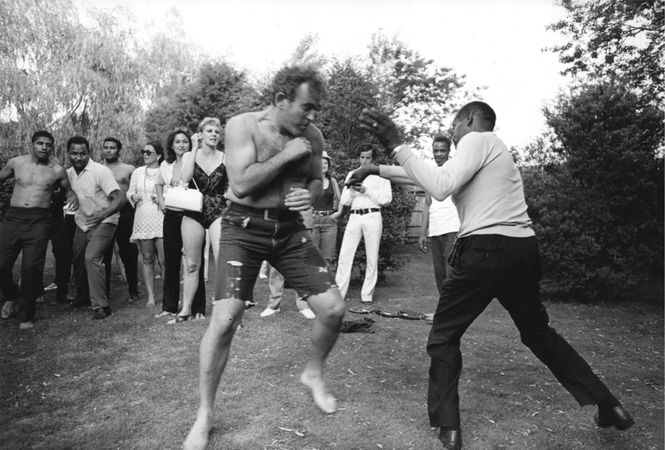

Norman Mailer and Rip Torn on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer and Rip Torn on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer and Rip Torn on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

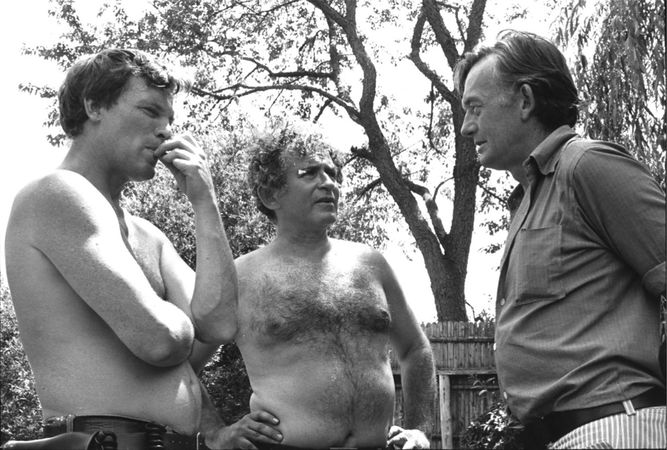

Norman Mailer with D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

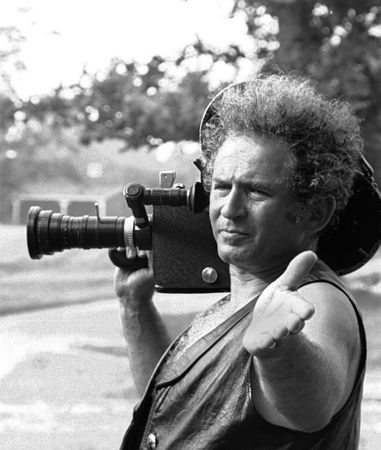

Norman Mailer with camera on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer on set of Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

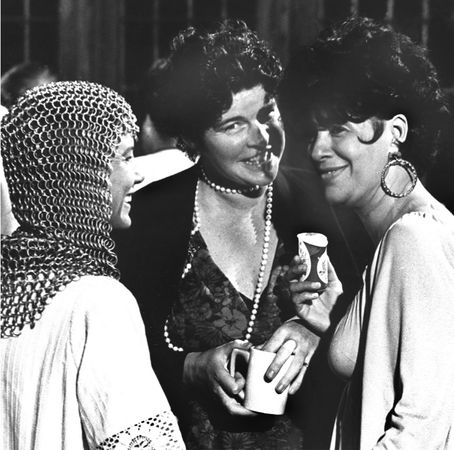

Norman Mailer’s ex-wives Beverly Bentley, Lady Jean Campbell, and Adele Morales on set of Maidstone, Long Island, 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

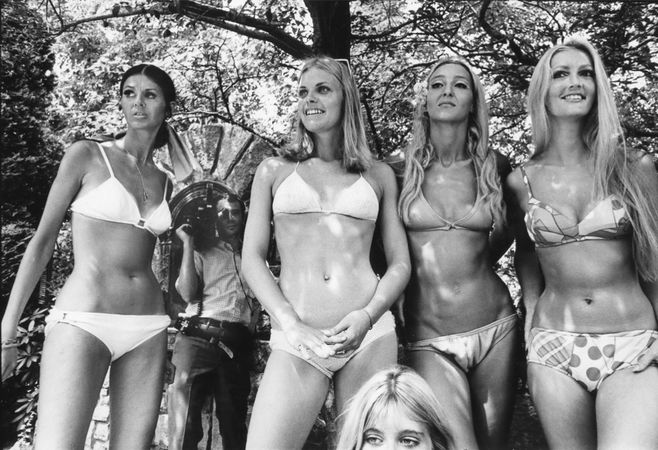

Bikinis on set of Maidstone, Long Island, 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

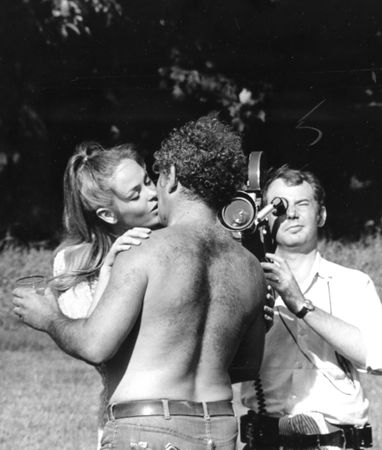

Norman Mailer directing, Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

-

Norman Mailer directing, Maidstone, Long Island 1968 © Daniel Kramer.

Pictorial Sequence by Daniel Kramer.