The Mailer Review/Volume 9, 2015/Parallel Lives: Difference between revisions

m Updated byline box. |

m Grlucas moved page Parallel Lives to The Mailer Review/Volume 9, 2015/Parallel Lives |

||

(No difference)

| |||

Revision as of 06:33, 4 July 2020

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 9 Number 1 • 2015 • Maestro | » |

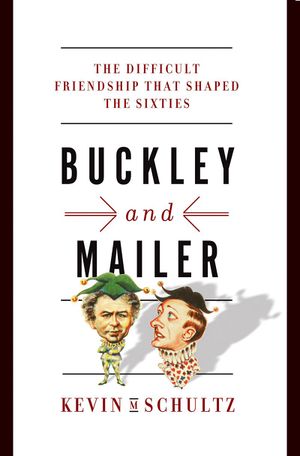

New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015,

400 pp. Cloth $28.95

In 2013, an article in Esquire teased “What Would Norman Mailer Think of the Tea Party?”[1] While the Tea Party came to national prominence only after his death in 2007, those of us who are familiar with Mailer’s work could likely guess what he might think of this political movement. Some insight into the height of Mailer’s political activism and public importance might help shed some light on this question and is one-half the subject of Kevin M. Schultz’ new book Buckley and Mailer: The Difficult Friendship That Shaped the Sixties.

As the title suggests, Schultz considers Buckley and Mailer at the zenith of their political influence and popularity in the American political arena in the 1960s. It’s a biography — sprinkled with literary criticism and history — of what Schultz sees as the parallel and public lives of two towering figures that helped shape the political and social reality of the disruptive and turbulent times after World War II. “America” no longer stood for all its citizens, if it ever did. While the Liberal Establishment had succeeded in achieving relative stability after the war, it had also imposed assumptions on how to live that meant to homogenize thought and curtail options its own view of “America” — think Leave It to Beaver and the Boy Scouts.

Early in the book, Schultz outlines these dominant assumptions: a belief that progress could be achieved through rational thought and the technological products of that thought; a belief the moral righteousness of corporate capitalism; and a belief in The Rules that upheld the moral center of American life. The Rules, Schultz explains, asked people “to temper their views, to speak in greys, to scuttle deeply held positions, to be respectful of others above all else.”[2] They taught how to dress (“a collared shirt and tie for men and dresses for women”), how to behave (no sex before marriage; no divorce; respectful address; and certainly no homosexuality), social responsibilities (church on Sundays; children should be seen and not heard; men were strong caretakers; women were emotional and not members of the public sphere), who to respect (John Wayne and Frank Sinatra; White Americans over Black Americans), and what to believe (rational thought would lead to the perfection of mankind; corporate capitalism produced the technologies that would deliver that perfection).[3] The inadequacy of these beliefs to unify all facets of America begins to fray the social and political tapestry in the 1950s and leads to movements in the 1960s that seek new answers to what makes life worth living.

Schultz positions Buckley and Mailer both as somewhat knightly figures doing battle on the stage of the American theatre. They were epic warriors — heroes who wanted to preserve the “virtuous American heart” that could still provide a unifying center within the corrosive elements of the Cold War, the nascent Civil Rights Movement, and the American military presence in Vietnam. Both men had already become celebrities by the time of their first debate in 1962 — a debate that Schultz shows propels them to national prominence and secures their life-long albeit uneasy friendship. While much of Buckley and Mailer contrasts the two men — from their very different physical appearances to their fundamental disagreement on what political and social reforms were necessary to save America — it does not ostensibly choose sides in the debate and is more interested in their similarities. While Schultz seems careful not to show a preference toward either man, there is perhaps a slight bias toward Mailer.

Buckley and Mailer were both born in the 20s, earned Ivy-League educations, served in World War II, achieved an early celebrity, founded journals, became public intellectuals in the early-1960s, shone as icons for their respective movements in the 60s, saw those movements move beyond their sway, ran for mayor of New York City, and continued to write and enjoy success for the rest of their lives. Yet, Buckley and Mailer centers around the height of their influence in America: the 1960s. Schultz presents both men as major intellectual forces of the time as America struggled with war and inequality.

While Buckley and Mailer examines the influence that these two men had on the 1960s, it also makes clear that our era shares much of the trouble that characterized theirs. It’s full of “sound familiar?” moments. War, fears about national security, and the fight for racial and gender equality seem to be the ever-present bête noirs of U.S. political and social reality.

Yet — and perhaps this is the greatest implied contretemps of the book — we have no towering figures like Buckley and Mailer to help guide us through them. While Schultz does not flinch at showing the flaws of both men — their respective problems addressing race, for example — neither was afraid to engage these issues in a public way, even if the answers weren’t readily apparent. They were intellectuals who used their public esteem to hash out the problematic issues — they did not appear on TV with everything figured out, with ready answers for the country’s woes. The public forum was an integral component of the thought process — a model of how engaged citizens in a democracy should work to find meaningful answers. They modeled the difficult responsibility and the moral necessity of what it takes to live in a democracy. It’s messy. Sometimes you get it wrong, but you need to keep trying, even when you look like a fool. Both Buckley and Mailer were no strangers to that feeling. While Buckley’s conservatism provided the foundation for his approach and Mailer’s radical, sensual rebelliousness guided him, the media provided a forum for debates that actually seemed to make a difference in helping people come to terms with their individual situations — contrary to today’s media and political landscape: isolated and hermetic, anti-intellectual, partisan, and resolute.

Both Mailer and Buckley seemed to sense this new reality at the end of the 60s. Both men’s stars were fading in the national spotlight, and both became uncertain about the country’s future. The violence and anxiety of the sixties seems to have birthed many children, each only interested in its own rights to life without any sort of national identity. Perhaps one of the problems lays in our networked world where every voice has equal authority when what we really need are those voices more qualified to get to the heart of the matter. Schultz’ book implicitly asks: who are the figures we look to for guidance today? Are they deserving of our attention? Our devotion? Do they struggle heroically with the difficult issues of the day? Make mistakes? Increasingly, it seems the answer is no. Early in the 1970s, Buckley predicted a new era dominated by celebrity, John Wayne’s speech at the RNC seemed to provide a model for politicians and citizens today — an unthinking devotion to celebrity that lionizes patriotism above skepticism.[5] Celebrity and technology have replaced critical engagement with entertainment.

Perhaps this is why Schultz’ book begins with death. Buckley reads of Mailer’s death in 2007 — a victim of his own waning health. Buckley, too, would pass early in 2008. It’s as if the death of these men signifies the true end of an era in America. Schultz often takes on the role of the limited-omniscient narrator for both figures; here Buckley muses:

But none of the obituary writers seemed to understand Mailer’s larger project, his effort to remake the country, to open its possibilities, to divorce it from its lineage of Cold War liberalism and deadening technological bureaucratization in a grand scheme to create something more fulfilling, more in touch with what it means to be human. In short, they missed all the reasons Buckley loved the man, and loved to argue with him. They missed the most important part.[6]

This passage becomes Schultz’ thesis for the book, for both men. Buckley and Mailer were ultimately trying to answer the most profound question in life: what makes life worth living? Both struggled with this question, in private and in public. Each endeavored to produce “a revolution in the consciousness of their time” by questioning the authority of the “shits” that Mailer saw “killing us.”[7] It was this public struggle that makes their contributions so important.

Maybe this is the underlying implication of Buckley and Mailer. While the latter’s technophobia is well known and documented by Schultz, Mailer was no stranger to the popular media of his day. While he would likely define himself mainly as a writer, Schultz’ study concentrates more on Mailer’s genre bending: his use of journalism, television, speeches, public appearances, and film. Mailer understood that “[m]odern minds need modern media” and was unafraid to try his hand at everything, including Legos.[8] Perhaps this is our challenge in the digital age. Where the playing field is leveled and it seems only the loudest voices can be heard, maybe it’s our duty to use Mailer (and Buckley) as examples. Since Mailer felt it was his duty to use whatever means (media) necessary to reach a distracted nation, maybe we, too, have a moral responsibility to use social media for our own everyday activism. Instead of posting cat videos and the latest meal we had at Shake Shack, maybe a better use of Facebook would be to promote awareness of racial inequalities, elicit action for a local Occupy meeting, or help carry on the legacy of, say, Norman Mailer. Ironically, maybe the technologies that Mailer considered most dubious can help continue his legacy of social activism — with our help.

Buckley and Mailer, therefore, is a timely book. It’s a celebration of their lives, how they helped shape the sixties, their continuing importance in assessing 20th-century American politics, and their genuine love for their country. Buckley and Mailer is not weighed down by academic language — doing much to make the narrative of these great men accessible to a wide audience. It reads like a novel, with flashbacks, anecdotes, humor, and the occasional pathos that illustrates Schultz’ respect and enthusiasm for his subjects. This accessible style does not belie a lack of research, however. It has copious notes and support, documenting the relationship of these two giants with plenty of research gleaned from both primary and secondary sources. Schultz’ study reminds us how important the sixties were in shaping the America that came after, and told through the lens of Buckley and Mailer, makes it all the more interesting and significant. Any college seminar that examines America in the 1960s would benefit by including Buckley and Mailer on its syllabus.

In addition, Schultz’ book seems to wax nostalgic for an America that respected public intellectuals and actually needed them to guide the national discourse. While Schultz observes that both Buckley’s and Mailer’s significance in U.S. politics waned in the seventies, not many artists and intellectuals have replaced them in the national consciousness. Whereas the voice of the educated and critical used to be a significant part of the popular media, they seem to have been replaced by a cult of celebrity and fear that uses the media to sell an ideology, the latest computer for your wrist, and lots of wars to keep us safe, secure, and unthinking. Who are the public intellectuals today that fight for the heart of America? With the death of Christopher Hitchens in 2011, maybe the old-school public intellectual can no longer speak for a country defined by big butts, small computers, disengaged citizens, and greedy oligarchs. Have we finally become what both Buckley and Mailer feared? Discontent is still evident in the U.S. — see Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Moral Monday, Fight for 15, the People’s Climate March, Move to Amend, and other activist movements — but what we seem to be missing are powerful, smart voices to give them direction, gravitas, and longevity.

After reading Buckley and Mailer, am I any more confident speculating as to what Mailer might think of the Tea Party? Perhaps this is the wrong question to ask. Buckley and Mailer did not share similar political views, but they both agreed that standing up for your beliefs, engaging opposing viewpoints, and supporting those ideas in a public venue are integral for a healthy democracy. Schultz makes clear in Buckley and Mailer that each man considered it his responsibility to help build America’s future by being warriors who battle in the public arena, sometimes winning, frequently getting battered and bruised, and ultimately knowing when one’s time on the field of battle has passed. Buckley and Mailer pays respect to the public significance of these two figures at a time of national disruption and seems to be an implicit invitation for others to take a similar responsibility today. It is a timely book and a timely call.

References

- ↑ Martelle, Scott (October 10, 2013). "What Would Norman Mailer Think of the Tea Party?". Esquire. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ↑ Schultz, Kevin M. (2013). Buckley and Mailer: The Difficult Friendship That Shaped the Sixties. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 55.

- ↑ Schultz 2013, pp. 58–62.

- ↑ Word cloud and textual analysis via Voyant Tools.

- ↑ Schultz 2013, p. 241.

- ↑ Schultz 2013, p. 17.

- ↑ Schultz 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Schultz 2013, pp. 229, 269–271.