The Mailer Review/Volume 3, 2009/Maidstone: A Sign of the Times

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 3 Number 1 • 2009 • Beyond Fiction | » |

Griselda Steiner

Abstract: An interview with actor Rip Torn that focuses on his recollections of the production of Maidstone (1970).

Note: This interview first appeared in Filmmakers Newsletter in September 1971. Reprinted with permission of Griselda Steiner.

URL: https://prmlr.us/mr03ste

Norman Mailer’s film Maidstone scheduled to be released this year, in which he campaigns for President as a movie director under the name of Norman T. Kingsley, was made in the Hamptons in the summer of 1968, when most New Yorkers were sunbathing while listening to pre-convention news on portable radios. Mailer runs a campaign on film in which the leading political figures have been assassinated and the remaining contenders are from show business. The swift parade of political events which followed the film’s completion has not undermined the power of its message. Maidstone elaborates on the Presidency, Vietnam, Black Power, student riots, the CIA and issues of the Revolution. This movie, shot in 16mm, is an excellent vehicle by which to study Mailer—the man and his creative process.

Mailer is quoted as saying, “The existential exists in the act precisely because its end is unknown.” Aside from a Victorian narrative of a lady reporter, played by Mailer’s third wife, Lady Jean Campbell, the act, or event of making a movie becomes the movie itself. Mailer brought filmmakers, various friends and wives to the Hamptons for four days of shooting. He came prepared with outlines of the plot and biographies of the major characters. Casting, directing and action were improvised within the film.

Mailer’s unorthodox approach increased tensions between himself and others involved in the film, which can be witnessed on screen. By working without a script, he relinquished creative responsibility and depended on the imagination and spontaneity of his crew. The essence of being a human being is acting. When a camera is turned on a person and he is asked to be natural, he is stripped of all defenses. At the end, Mailer discusses the experience with his crew, taking them out of the context of their roles and thus exposing their hostilities.

The atmosphere of the Hamptons that summer was “camp,” created by the ironic contrast of a peaceful stretch of beach against the frantic lifestyle of the city scene makers. In the film, a sequence in which Black youths confront Mailer is true “camp.” The youths left the ghetto in the hot summer to spend time in a camp called Boy’s Harbor and met with Mailer in a plush mansion only miles from the city. Unimpressed, they brought their anguish with them. Mailer allowed them to express themselves with more freedom than any politician now in office.

Mailer’s “camp” was a campaign—a struggle to realize his creative power through mise-en-scène. Mailer realizes his fantasies on film with an almost childlike belief in his power to bring dream to life. As in his other films, Wild 90 and Beyond the Law, Mailer develops a structure on film, which he interrupts by florid speech making, leading into the nostalgic realms of his other self. Away from his wife in the male whorehouse, his sexual fantasies are realized. They make him timid. He is mad at this wife for retaliating by going off with a “Black stud” on a motorcycle.

The film was originally three hours long, but was cut to its present one hour and fifty minutes after months of careful editing. Mailer was reluctant to give any precious moment to the editing room floor. His letters home are long. Orson Welles in Citizen Kane kept the relic of his childhood—a sleigh named “Rosebud”—among his worldly treasures in the cellar of his mansion. Throughout the film, Mailer carries the statute of his wife’s head, “Maidstone,” perhaps in memory of the virgin snows of his childhood dreams. The title of Maidstone is popular in the Hamptons and derives from a village in England of that name.

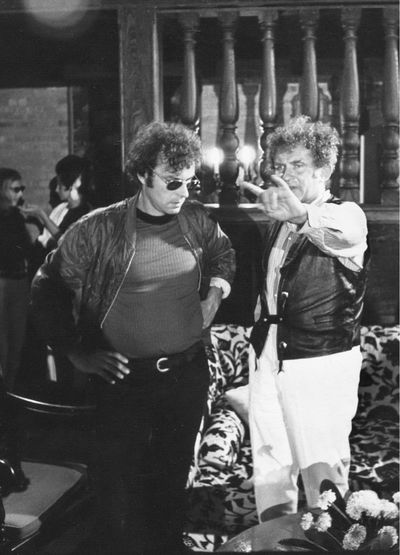

Mailer’s violent fight with Rip Torn, who plays his half brother in the film, is its most moving sequence. Rip Torn confronts Mailer and tells him he believes that an assassination attempt is the only fitting end. “Norman T. Kingsley, I have something for you.” He then proceeds to hit him twice on the head with a toy hammer. Mailer has always feared betrayal. His fame has made him vulnerable to jealous as well as justifiable attacks and his commitment to unique social concepts, a target for political enemies. Today, America’s revolution has all the qualities of a grotesque “camp.” The film Maidstone is part of this “camp”—an absurd statement in an absurd time.

The following is an interview with Rip Torn in which he answers questions concerning his experience in Maidstone.

Steiner: When did you first meet Norman Mailer?

Torn: About twelve years ago. He liked a girl that I liked and didn’t like me for that reason. He was very angry at me for a number of years and then found out in essence that I hadn’t done something he thought I had done. He had just misjudged me. Later, when he saw me act in The Deer Park he said, “I didn’t know that you were that good an actor. You’re a much better actor than I realized. How could I have missed that?” I said, “Maybe you were just subjective.” He said when he heard my name mentioned he used to spit on the ground.

Steiner: I remember a scene in Maidstone where you were drunk and fishing. What was happening?

Torn: I was fishing with a spinning rod. I wasn’t fly-fishing and I wasn’t drunk. I wanted to fish and the man was disturbing my fishing. He was getting into some hypnotic rap and I told him to get out of playing the role of a preacher government agent.

Steiner: What is the film Maidstone about?

Torn: It’s about assassination. Norman asked several people to set up phony assassination attempts. I think they just didn’t follow through. I was going to play his half brother Raul O’Hollihan. He told us that I had an alliance with a Black Nationalist group. We had a relative that was part African. There was a section of the film where I said I had gone to Praireview A&M and that’s a Black school. There are people in the South who are part African and have blue eyes.

Steiner: Did you direct any of the film?

Torn: I worked as an associate director. I didn’t sleep for five days. I set up the assassination scene. I wasn’t about to do that scene if there wasn’t a camera and sound on. I played the scene when I had a hammer in my hand. I thought he knew I was going to do it. He said he knew something; he knew I was “wired.”

Steiner: It looked to me as if you got into a real fight.

Torn: Well, that was because he didn’t play dead. He didn’t fold. I didn’t really smash him. I popped him. I had to fell the blow. Not only am I accused of hitting Norman with a hammer, I am also accused of biting his ear. Well, Norman bit my ear. I didn’t bite his ear.

Steiner: Why did you hit him?

Torn: I was not mad at him and, as I told sixty people on this film, I didn’t want to do this scene anyway, because no matter what I do, when I do a violent scene, it’s misinterpreted. Check the records of the hospital and see how severe that hit was and you’ll find it was minor. Just as the lacerations on my ear were minor.

Steiner: Was Norman mad at you?

Torn: He was angry for several years till he put the film together. The film doesn’t make it without that scene. He said, “Don’t let me know when its coming—try to surprise me.” If someone was there guarding him and thought it was the real thing, they would have done me in.

In many movies I think I’m hired to carry the “heavy.” There’s an element of trust there. That was the nature of Norman’s speech in the Hilltop Hotel that the film was built on trust. If he hadn’t trusted me, he would not have asked me to set up that phony assassination attempt. But by actually doing what he asked me to do, he thought I had betrayed him. If I had not done that action, I would have truly betrayed him. I think that somewhere inside he would have always despised me for not coming through. I was thinking of an association that was to last my whole life.

Steiner: Do you think people in the film felt hostility towards Norman?

Torn: Tremendous hostility built up, like a thundercloud. He did that deliberately. He did things out there to people that were cruel. He wanted to see how much they could take. His good friends jumped right back at him, like Bonzo and the scene with Buzz Faber.

Steiner: Is the film politically relevant?

Torn: I think it has resonance of the whole Bobby Kennedy assassination.

Steiner: How do you feel about Mailer?

Torn: He’s a life actor on the world stage. I think the thing that is not known about him is his loyalty to his friends, his relatives and his parents and his feeling to his ex-wives and particularly to his children. I feel brotherhood towards him.

Steiner: He has a reputation as a fighter. Do you think he provokes fights?

Torn: No. I have seen on three different occasions fights where he has gone out of his way to avoid trouble. But people just don’t leave him alone. I understand because I have some of those problems myself.

Steiner: Do you think an improvised film like Maidstone offers more than a structured film?

Torn: If you can set up the right situations. A genius makes certain inspired guesses about people. A priori he’s a genius. There are several geniuses drifting around this town. Mailer had very bright people in there. There were a lot of literary people who were talking dialogue that was better than any Hollywood writer could write for them. At the end of the picture there’s a very powerful line. After the fight, the kids were crying and I said, “Don’t cry baby. This is just another scene in your Daddy’s Hollywood whorehouse movie.” This I felt was a true feeling, even though I was a character, I felt I was a patsy.