The Mailer Review/Volume 1, 2007/Norman Mailer as Occasional Commentator in a Self-Interview and Memoir

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 1 Number 1 • 2007 • Inaugural Issue | » |

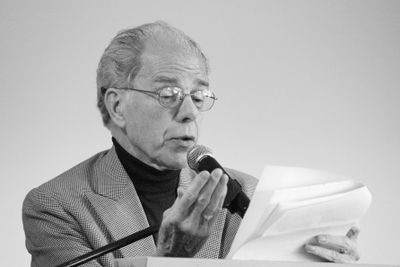

William Kennedy

Abstract: I decided Mailer didn’t have a style. He had a huge brain, which I couldn’t imitate. In those early days I didn’t have a brain, only a hunger. I was reading Mailer and Dos Passos as if they were contemporaries of each other until I discovered Mailer owed a debt to Dos Passos, as did I, and that it was visible in The Naked and the Dead through his use of the Time Machine, and the Chorus, which seemed inspired by the Camera Eye and the Profiles in USA.

URL: https://prmlr.us/mr01ken

I started writing fiction in college and when I was drafted during the Korean War I had a post-graduate education through my army buddies who were a literate gang. We were all running a weekly army newspaper in Germany and after the workday at the Enlisted Men’s club in Frankfurt we guzzled heilbock and dunkelbock and talked about writers—Sherwood Anderson, Hemingway, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Algren, Katherine Ann Porter, Flannery O’Connor, James Jones, Irwin Shaw, Thomas Wolfe. And Norman Mailer. Once in a while somebody mentioned Chekhov. I read everything I could find by all of them, and realized that the writing I’d done since college was all blithering drivel and that I was into something truly new by matching myself against these maestros. When I left the army I got a job as a newspaperman. I wrote short stories on my days off and found I could turn out dialogue that sounded very like Hemingway, I could keep a sentence running around the block like Faulkner, I could describe the contents of a kitchen refrigerator just like Thomas Wolfe, I could use intelligent and not-so-intelligent obscenity with the panache of Norman Mailer. None of this had much to do with Kennedy.

Kennedy did emerge, but only after shucking off all those maestros, who were smothering him. Of course you don’t really shuck them. They form your voice, your syntax, your wit or solemnity, your political inclinations, your defiance, your creative mysteries. Where does that insight come from?

page 11

What a great style—how do I get a style? I remember deciding Graham Greene didn’t have a style; he was merely intelligent. I decided Mailer didn’t have a style either. He had a huge brain, which I couldn’t imitate. In those early days I didn’t have a brain, only a hunger. I was reading Mailer and Dos Passos as if they were contemporaries of each other until I discovered Mailer owed a debt to Dos Passos, as did I, and that it was visible in The Naked and the Dead through his use of the Time Machine, and the Chorus, which seemed inspired by the Camera Eye and the Profiles in U.S.A.

Dos Passos had made a major impression on many writers. Steinbeck emulated him in segments of The Grapes of Wrath, inserting segments he called ‘generals’ to parallel his story. Jean Paul Sartre wrote in 1936 that he considered Dos Passos “the greatest writer of our time.” I remember the Dos Passos sketches were like Mount Rushmore carvings of seminal figures of the age—Woodrow Wilson, J. P. Morgan, Teddy Roosevelt, Jack Reed, the Unknown Soldier, whereas Mailer’s Time Machine segments were humanizing profiles of major characters from his narrative. I liked the intrusions of both writers so much I put multiple variations of them into my second novel, Legs, about the celebrity Jazz Age gangster Jack (Legs) Diamond. I used excerpts from newspaper movie listings, from gossip columns and prayer books, murder and speakeasy statistics from Prohibition, monologues about Jack Diamond by Trotsky, Carl Jung, and Einstein; an infrastructure that paralleled reincarnation in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and recurring interludes of a movie cameraman filming Diamond’s life as a newsreel I was inventing. A few of these things are still in the novel, but I cut away most of them in the eighth draft of the book after I admitted that my intrusions had become intrusive. Yet creative enhancement of a similar order continued in my later novels, all arising from my desire to write beyond the bounds of conventional narrative, beyond naturalism, beyond realism, a nod to the element of dream, fantasy, or my unconscious intentions, whatever they might be. And I came to see that I was interested in characters in extreme conditions—an aristocratic woman whose sexual fantasies edge her toward madness. A bottom of the world bum, a gangster, a columnist’s surreal life during a newspaper strike.

In 1967, the year I sold my first novel—about that columnist—I had another distant association with Norman—sharing a publishing house, the Dial Press and its editor in chief, E. L. Doctorow. Dial had published Norman’s American Dream and in 1967 they bought my novel, The Ink Truck.

page 12

Doctorow was the significant link (along with another editor, the late Donald Hutter), but Doctorow left Dial before they actually published my novel in 1968, and he went off to write The Book of Daniel. But I forgave him his flight, for he was the man who first said, “You’re a hell of a writer and we want to publish your wacko novel.”

The year I sold that book I was back at my old newspaper, the Albany Times-Union, after seven years in Puerto Rico and Miami. I was a poverty case, working half time for a hundred dollars a week in order to write my novel five days a week, always threatened by foreclosure. I was a muckraker in the Albany slums, writing voluminously about blacks and the white poor, a vital time as a newspaperman; and I was so imbued with the civil rights movement that I turned it into The Ink Truck, even though the book doesn’t read that way. It is a comic story of the columnist named Bailey and he is the first of my extremists, a wild man who transcends any orders the Newspaper Guild’s leaders give the strikers. He burns down a house where gypsy scabs are living and inadvertently kills the Gypsy Queen. I had covered a story about a gypsy queen dying in a hospital years earlier, and yet another gypsy queen would die in Albany Hospital during the week my novel was published years later, a moment of synchronicity that is too weird to reconstruct here. Bailey is kidnapped by the angry gypsies, is beaten, humiliated, tortured, drugged, turned over to a nymphomaniac who uses him as her slave to operate her sex machine; and finally, when the union capitulates to the company and ends the strike, Bailey keeps striking all by himself and loses everything but his solitude. His world is taken away.

I felt this same fear of loss when I was writing the novel but in quite a different way; and the fear intensified after I became a film critic. I had been a movie fanatic since seeing Buck Jones movies with my father at age six, and in the late sixties I stopped muckraking and started the life of a critic—covering the New York Film Festival at my own expense in order to see free films. I might see five films in one day. I also paid to see Norman’s first film, Wild 90, then saw his second one, Beyond the Law, and after meeting his editor and sometime cameraman, Jan Welt, who was from Albany, I met Norman for the first time and talked to him briefly after Jan screened for me half an hour of his third film, Maidstone. Norman was editing that film himself and when I asked for an interview he brushed me off with a smile. Flipping a can of film from hand to hand he said he needed to work very hard or else he would soon be out of the movie business. Also, he said, he had no time to

page 13

“make marks for immortality,” and that writing about Maidstone before its release would be like “giving caviar to a spaghetti eater.” That sounded like condescension to us spaghetti eaters, and I put it into the newspaper.

What Norman was doing—directing films—was something I had fantasized. These were the years of the incursions into our psyches by great foreign filmmakers—Bunuel, Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and also the emergence of the auteur theory, which elevated Hollywood directors such as John Huston, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Joseph Mankiewicz to the level of visionary artists in what most of us had considered collaborative enterprises. The directors, in this new auteurial sense, were made the equivalent of a novelist—the central creative mind responsible for these belatedly recognized works of cinematic art. Also at this time the novel was again being diagnosed as terminal, and there was no doubt it had lost the clout it had had twenty years earlier. The novelist was being shoved offstage and the movie director was coming up front and center.

Norman wrote about this, and the urge to direct grew in me. I considered hedging my bets in case the novel went the way of the narrative poem—move into the film world first as a screenwriter, then graduate to being a director. But I had no chance. I was rooted with a family in Albany, and Albany could not even be considered a backwater of the film industry—although today it has raised its profile almost to backwater status. I also had no intimate knowledge of how a movie was made, which may have kept me honest as a film critic—judging the achievement not the methodology; but I could just as easily have become an astrophysicist as a movie director, and I came to understand this and kept on writing novels. This was neither cowardice nor resignation, but a brilliant and salvational insight into that which I was not.

In the following decade I became a screenwriter out of desperation, pitched an idea for a movie treatment to a producer, and in 15 minutes made more than I’d earned all year as a teacher and freelancer. Nothing came of my treatment except it saved our mortgage. In 1983, when I no longer needed money, I was hired to write a screenplay with Francis Coppola for The Cotton Club, and we reconstructed the movie from scratch after six previous scripts had been written, four by Mario Puzo, two by Coppola alone. He and I wrote something like forty drafts, which was madness. After about the fifteenth draft Francis said to me that in three years I’d be directing my own movie; but I said no, I don’t want to get up that early. I was long rid of the directorial fantasy, and also, having been managing editor of a daily newspaper,

page 14

I never again wanted to be responsible for other people’s work. A few years later I wrote the script for Hector Babenco’s film of my novel Ironweed and in the past 20 years I’ve made some decent money writing scripts that were never made. This was a sideshow to my center ring performance as a novelist. I was, and will remain, a one-man band.

But to resume on Norman, I had great admiration for his persistence as a director and I wrote about his films. In Cannibals and Christians he had used the self-interview to assert himself and I was impressed. So in writing about his first film, Wild 90, I used the form but with a variation: “The Self-interview with the Absent Subject as Occasional Commentator.” I culled Norman’s comments from wherever I found apt responses to whatever question I asked myself. That old interview is partly resurrected in what follows, along with updates. Also the absent subject is not absent but sitting over there.

interviewer

It is common knowledge that Wild 90, which was extremely obscene in its language, generated such heavily negative reviews that Norman took out an ad in The Village Voice to acknowledge them.

Norman

In the teeth of this reception and with full admission that Wild 90 is a minor effort, modestly made, with a sound track difficult at times, I would say that I think it’s an important picture. I go so far as to believe that in 10 years it will be a private classic.

Kennedy

Norman writes fiction in the major league and his perceptions on the personality of America go deeper than just about anyone writing for magazines these days. But the movie doesn’t compare.

interviewer

What about all that obscene talk? All that profanity?

Kennedy

We’ve been through Henry Miller and James Jones and William Burroughs. …There are no more language frontiers. As to Wild 90’s existential excitement, which Norman discusses in Esquire, what would really validate it is an

page 15

artistic achievement on the surface level of the film. Actually Wild 90 is miles ahead of much of the underground glop being seen today, and it’s important because Norman made it.

interviewer

Norman had a lofty ambition when he made the film.

Kennedy

Of course he did—to change the American consciousness, his fundamental vocation since he was in the womb. He sees America as two lobes of one brain.

Norman

Two hemispheres of communication themselves intact but surgically severed from one another. Between the finer nuances of High Camp and the shooting of firemen in race riots is, however, a nihilistic gulf which may never be negotiated again by living Americans. But this we may swear on: the Establishment will not begin to come its half of the distance through the national gap until its knowledge of the real social life of that other isolated and—what Washington will insist on calling—deprived world is accurate—rather than liberal, condescending, and overprogrammatic. Yet for that to happen, every real and subterranean language must first have its hearing, even if taste will be in the process as outraged as a vegetarian forced to watch the flushing of the entrails in the stockyards.

interviewer

And so Wild 90 was born.

Kennedy

Norman also feels he must undermine good taste.

Norman

Good taste, we would submit, may be ultimately the jailer who keeps all good ladies and angels of civilization installed in the innocence of their dungeon.

interviewer

You think he’ll succeed in those aims?

page 16

Kennedy

Even though he thinks it’s the foulest-mouthed movie ever made (his line), it’s still got to get through that barrier of good taste that the other half of America has erected. And that penetration is possible only through art … the kind of art Mailer’s essays are made of. He reaches people that way. He does change consciousness with the brilliance of his thought. He’s changed mine a few notches, for which I thank him.

Norman

The irony is that most of the people who are hostile to my work are precisely those people who have the deepest sense of what I am writing about.

Kennedy

I am not hostile to his work.

interviewer

That’s a defensive remark.

Kennedy

I don’t want to be misread. Norman remains the feistiest talent in the room, with too many facets to that talent to focus on a single direction, always heading toward the new. The Scott Fitzgerald cliché is that there are no second acts in American life but Norman is in his fifth act, at least, and holding his own. But the establishment is actually beginning to catch up with his bad-boy radicalism. And what will Norman’s role be when he can no longer shock anybody in the name of progress? Will he wither away? Take up pure literature? Join the establishment? Lose his soul?

Norman

No, as always, I have spent my time talking of disease. But then there is no end to metaphysics, they say.

interviewer

Wild 90 was only the beginning of Norman’s moviemaking. What about his other films?

page 17

Kennedy

I saw only that half hour of Maidstone. I met Norman in L.A. when he was publicizing Tough Guys Don’t Dance, and saw it after a cocktail party and not since; so memory isn’t trustworthy. I did review and praise Beyond the Law, his second film, which closed the New York Film Festival in 1968. Donn Pennebaker, the cameraman on Wild 90 admitted the first film had flaws but said by his fifth film Norman will be on to something. With Beyond the Law, about one night in a New York City police station, he was already on to something. This and John Cassavetes’s Faces were the two films at that festival with the truest sense of being about real life, life overheard and unrehearsed. Faces, it turned out, had been rehearsed endlessly, and yet it did seem spontaneous. Norman was the spontaneous star of his film as a cop, moving from an adenoidal Texas drawl to a shamelessly thick Irish brogue, delivering monologues I thought would make first-rate reading, but which I had trouble hearing in full because of a troublesome sound track. But I did recommend the film to anyone interested in new cinematic directions, for it fused cinema verité with the literary imagination and willful improvisation. At the press screening Norman was asked about the influence of film on his writing and he said seeing himself on film as he edited Wild 90 gave him the idea to become an object in The Armies of the Night, and to write of himself in the third person.

Norman

Since there had been way too much of me in the rushes, I had come to see myself as a piece of yard goods about which one could ask, “Where can I cut this?” The habit of looking at myself as if I were someone other than myself—a character ready to be described in the third person—had already been established. Parenthetically, I think it’s also a way of getting your psychiatry on the cheap.

Kennedy

That third person he called “Norman Mailer” in The Armies of the Night turned out to be the protagonist of one of his greatest books. But the old Norman as first-person was already a wizard, as I discovered in Advertisements for Myself.

Norman

When I wrote [Advertisements] I realized that one could literally forge one’s career by the idea you instilled of yourself in others. That is, impersonate the

page 18

person you might have some reasonable chance of arriving at in a couple of years and soon enough you are lifting yourself by your bootstraps. It is an unbelievably demanding task…

Kennedy

Norman’s impersonation in Advertisements, with his ego as the turbine for the prose, was revelatory. I’d never before encountered an ego that large, and it was bracing. I said earlier he had no style, just a big brain, but in this book his style flowed like Niagara. A Mailer sentence was so sharp it zinged you, so fluent it rushed you along to the next zinger; and it was instantly recognizable. Give us a couple of sentences, Norman.

Norman

There was a time when Pirandello could tease a comedy of pain out of six characters in search of an author, but that is only a whiff of purgatory next to the yaws of conscience a writer learns to feel when he sets his mirrors face to face and begins to jiggle his Self for a style which will have some relation to him…. To write about myself is to send my style through a circus of variations and postures, a fireworks of virtuosity designed to achieve … I do not even know what. Leave it that I become an actor, a quick-change artist, as if I believe I can trap the Prince of Truth in the act of switching a style.

Kennedy

One of Norman’s quick changes was to become a reporter, a man who covered the most cosmic stories of the day, and he dazzled the world. I used to teach his reporting on the 1968 political conventions in Miami and the Siege of Chicago and also the Patterson-Liston fight, where he brought a new definition to the life of newspapermen, those ink-stained wretches of that wonderful bygone age in which I learned the news business, but which in Norman’s eye was more squalid than wonderful. With bruising insight he redefined the reporter, or the journalist, if you will. The great sports columnist Red Smith once said that you could always tell the difference between a reporter and a journalist because the journalist needed a haircut. This spoke not only to the journalist’s longhaired writing style but also to his financial status, so marginal he couldn’t afford the barbershop. This distinction is moot in our present hirsute age, especially so as it relates to Norman, who hasn’t had a serious haircut in forty years. But there he was, the literatus asTemplate:Pagjournalist, cavorting among the boxing writers, watching them drink, eat, freeload, and turn out copy. He called his story “10,000 Words a Minute,” and I taught it along with the reporting of Charles Dickens, James Agee, Hunter Thompson, Damon Runyon, A. J. Liebling, H. L. Mencken and other heroic figures of the word whose prose of the instant sometimes became literature. I taught these writers as an antidote to objective reporting, which bored me, as did the flatlined prose of feature writers of the 1950s and ’60s who were writing gruel and cold porridge—a neutered narrative wrapped in the homogenized ethics of the wire service culture—mainly the powerful Associated Press—which produced coverage that offended nobody who subscribed to their wire. The New Journalism, not really all that new, came to pass in part as a response to this pap, and there was Norman at ringside, wearing his journalism badge, squinting at the high-speed freeloaders.

Norman

Reporters … suffer each day from the damnable anxiety that they know all sorts of powerful information a half hour to 24 hours before anyone else in America knows it…. It makes for a livid view of existence. It is like an injunction to become hysterical once a day. They must write at lightning speed…. Writing is of use to the psyche only if the writer discovers something he did not know he knew in the act itself of writing. That is why a few men will go through hell in order to keep writing—Joyce and Proust, for example…. Think of the poor reporter, who does not have the leisure of the novelist or the poet to discover what he thinks. The unconscious gives up, buries itself, leaves the writer to his cliché, and @he# saves the truth … for his colleagues and friends. A good reporter is a man who must still tell you the truth privately; he has bright harsh eyes and can relate ten good stories in a row standing at a bar.\

interviewer

You were a newspaperman. Is Norman accurate on reporters?

Kennedy

He just encapsulated my biography. In college I was writing imitative fiction, but also seriously training to be a newspaperman. By graduation I was a pro, got a job as a sportswriter and also columnist, which was what I thought I wanted as a career. Red Smith, Runyon, Pegler, Mencken, Heywood

page 20

Broun were my collegiate models. Years later at the The Miami Herald I was covering all the revolutionary Cubans, a great beat, and writing short fiction before and after work, usually winding up asleep at the typewriter. Obviously being two kinds of writer wasn’t working. Kerouac had just published On the Road and I decided to do one of Norman’s quick changes and hit the road myself. When I told my editors I was quitting they offered me a daily column—the dream job—but it was too late. I took a very parttime job in Puerto Rico for almost no money and spent my days writing a novel, which proved to be zilch. I started another with promise, and then came an offer to be managing editor of a brand new daily newspaper. I knew what Mencken had said—that all managing editors are vermin—but I took the job anyway. I lasted two years, then quit again and haven’t had a serious job since. I had become, unequivocally, a novelist, not a journalist.

interviewer

Didn’t Norman confront that very same dualism?

Kennedy

He did indeed—as his other self. It came into sharp focus during an encounter with the poet Robert Lowell in 1967 when Lowell and the third-person ‘Norman Mailer’ were both marching on Washington, and went to a party hosted by Liberals where they were both going to be after-dinner speakers.

Lowell

I suppose you’re going to speak, Norman.

Norman Mailer

Well, I will.

Lowell

Yes, you’re awfully good at that.

Norman Mailer

Not really.

Lowell

I’m no good at all at public speaking.

page 21

Kennedy

They lapsed into silence, though Norman Mailer kept thinking about Lowell. Then Lowell spoke up.

Lowell

You know, Norman, Elizabeth [Hardwick] and I really think you’re the finest journalist in America.

interviewer

How did Norman Mailer react?

Kennedy

He didn’t react publicly but privately he was seething. Then Lowell said it again.

Lowell

Yes, Norman, I really think you are the best journalist in America.

Norman Mailer

Well, Cal, there are days when I think of myself as being the best writer in America.

Lowell

Oh, Norman, oh, certainly. I didn’t mean to imply, heavens no, it’s just I have such respect for good journalism.

Norman Mailer

Well, I don’t know that I do. It’s much harder to write … a good poem.

Lowell

Yes, of course.

interviewer

Mr. Kennedy, Do you think Mailer is the best writer in America?

Kennedy

Present company excluded?

page 22

interviewer

Of course. Otherwise how could I ask such a question?

Kennedy

Fine. Then how could I begin to argue with such a question? But we are getting to the end of my time and we should focus as a finale on what is truly important about writing novels. Don’t you think so, Norman?

Norman

Who can swear there has not been something catastrophic to America in the failure of her novelists?

Kennedy

Aren’t you being a little harsh?

Norman

No [American] writer succeeded in doing the single great work which would clarify a nation’s vision of itself, as Tolstoy had done perhaps with War and Peace or Anna Karenina…. Writers aren’t taken seriously anymore, and a large part of the blame must go to the writers of my generation, most certainly including myself. We haven’t written the books that should have been written. We’ve spent too much time exploring ourselves. We haven’t done the imaginative work that could have helped define America.

Kennedy

When we get to defining, or failing to define, America, I grow depressed. I knew I had failed before Norman told me. But then I cheer up, because I never really wanted to define America. I thought I wanted that forty years ago when I tried to shape a large novel that would track American history from the Dutch explorers up through Jack Kennedy, as it all played out in Albany, America’s oldest chartered city. It’s a rich history—the immigrant hordes coalescing on a landscape of frontiers, American capitalism inventing itself through railroad consolidation, Presidents spawned, great writers nurtured, majestic sinners flourishing and political wizards monopolizing everybody’s life forever. I soon realized I wasn’t up to the task and throttled down to the individual, for instance a novel about a pool hustler very like my favorite uncle. I called him Billy Phelan and he comes to crisis during a political

page 23

kidnapping when he refuses to be an informer. If I may, I’d like to invite Billy into this conversation, buy him a drink. Will you have a drink, Billy?

Billy Phelan

The last time I refused a drink I didn’t understand the question.

interviewer

I think we should get back to the serious novel.

Norman

The serious novel begins from a fixed philosophical point—the desire to discover reality—and it goes to search for that reality in society, or else must embark on a trip up the upper Amazon of the inner eye.

Kennedy

What I take home from that remark is that the novel’s choices are scope versus the self. Norman also says Hemingway and Faulkner both gave up on scope.

Norman

Their vision was partial, determinedly so; they saw that as the first condition for trying to be great—that one must not try to save. Not souls, and not the nation. The desire for majesty was the bitch that licked at the literary loins of Hemingway and Faulkner: The country could be damned. Let it take care of itself.

Kennedy

I remember a critic panning a self-absorbed novelist and saying rather neatly that literature wasn’t about the self, but what came home to the self through experience. Norman has written extensively about the self, about writing about the self, and against writing about the self. Norman seems to have written about every choice a human being can make; you can quote him to your own ends, whatever they are, like Satan quoting the Bible. I do remember a line I read 55 years ago and always credited to Norman—from The Naked and the Dead, I think, even though I can’t find it. One of his characters says, “I hate everything that is not myself.” I know such people, and a couple of them are writers. The writers write well but are only as worthy as the

page 24

originality they bring to bear on their solipsism, their narcissism: Hey you, listen to what the world did to me yesterday. Without me the goddamn world doesn’t exist. This point of view grows old swiftly.

Norman

The narcissist suffers from too much inner dialogue…. One part of the self is always immersed in studying the other part…. Other people … have value to the narcissist because of their particular ability to arouse one role or another in himself. And they are valued for that. May even be loved for that….

interviewer

Do you consider yourself a narcissist, Mr. Kennedy?

Kennedy

Life would be easier if I were. I’m in the position of always wanting self and scope in the same novel, but in measured doses. None of my books is long, but if you take them together—the Albany Cycle collected, from A to almost Z—I might get a B-plus for having scope. But the self is a problem. Any character who seems close to my own experience, even if it’s tragic, will bore me dreadfully.

Hemingway

Forget your personal tragedy. We are all bitched from the start and you especially have to be hurt like hell before you can write seriously. But when you get the damned hurt use it—don’t cheat with it. Be as faithful to it as a scientist—but don’t think anything is of any importance because it happens to you or anyone belonging to you.

interviewer

Why is Hemingway butting into this conversation?

Kennedy

Because I have him as a character in my new novel.

interviewer

Norman has Hitler as a character in his new novel. No narcissism there.

page 25

Kennedy

Indeed. But I hear he also has an assistant to Satan as a character. Everybody knows how devilish Norman is, so we’ll have to withhold judgment on this one. Who knows what unconscious elements are at work here?

Norman

The unconscious present within may have as many interests, aspects, principalities, chasms, terrors, underworlds, otherworlds, and ambitions as yourself. Your unconscious may even have ambitions that are not your own.

Kennedy

I think we should leave it there, with Norman having the somewhat ambiguous last word.

Hemingway

I am trying to make, before I get through, a picture of the whole world.

Kennedy

Thank you, Papa, but that’s quite enough. Norman told us all about you and scope. And thank you, Norman for stopping by. You have turned my consciousness.

Norman

I love the novel.

Kennedy

So do I. And so should all of you here today. Thank you for singing along with us novelists.