An American Dream Expanded: Difference between revisions

m →Blurbs and Snippets: Added caption. |

m Removed notice. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''An American Dream'' Expanded}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''An American Dream'' Expanded}} | ||

{{Aad-tabs}} | {{Aad-tabs}} | ||

Revision as of 11:58, 29 May 2019

| An American Dream | Expanded | Bibliography | Letters | Timeline | Word Count Comparison | Credits |

| “ | An American Dream is Norman Mailer’s first novel in nine years. He wrote it at a high pitch, each chapter appearing in Esquire while he was still at work on the next: a method now unusual but common enough among the great novelists of the nineteenth century, which contributed much to the quivering tension of the story.

The theme of challenge suggested by Mailer’s choice of this method is very much a part of the book. His hero challenges the Devil himself. Stephen Rojack kills his wife, lies to the police, is interrogated by them, discovers a woman, his wife’s opposite, in whom he senses the truth and strength he longs for. The ingredients of his story are deliberately those familiar from many a thriller or movie-murder—suspense, sex—but Rojack lives these experiences with a fierce intensity which shatters their popular image and reveals extraordinary meanings behind them. He is a man who believes in God and the Devil, and to whom God is courage, not love. His actions become explosively significant because he feels that any one of them might open the crack through which the Devil’s power, or that of God, could flood in. Simply on the level of ‘what will happen next?’ An American Dream grips relentlessly: will the suspicious police pounce on Rojack? Will he and Cherry, his new girl, be able to establish the love which has begun to grow between them? But beyond this there is the immense exhilaration springing from the boldness and passion with which Norman Mailer tackles his central theme of man as the battleground for God and the Devil. This is his most exciting book since The Naked and the Dead, which became a modern classic and has sold, over two and a half million copies in the English language. |

” |

| — Dust jacket text, British edition, Andre Deutsch, April 1965. | ||

Gallery

-

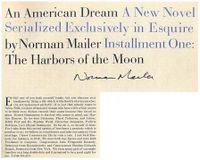

Title and opening paragraph of the first installment of An American Dream in Esquire, January 1964.

-

Cover of uncorrected page proof of the Dial Press edition.

-

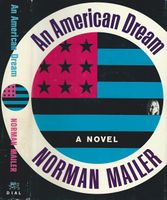

Front and spine of dust wrapper of the Dial Press edition.

-

Back panel of dust wrapper of the Dial press edition: photograph of Mailer by Anne Barry.

-

Advertisement in the New York Times for the Esquire serial version, 22 April 1964.

-

An early AAD cover mockup.

-

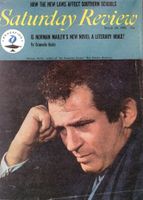

Cover of 20 March 1965 Saturday Review depicting Mailer.

-

Best seller list in Book Week, 30 May 1965, showing the novel in No. 10 position.

-

Best Seller list in New York Times, April 15, 1965, showing the novel in No. 3 position and in No. 5 position in the London edition.

-

Invitation to the reception for the novel at the Village Vanguard in New York on publication day, 15 March 1965.

-

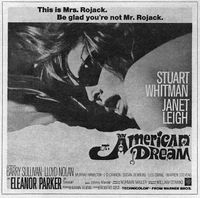

An invitation to the screening of the film An American Dream.

-

Advertisement for the film version of the novel from Warner Brothers Pressbook.

-

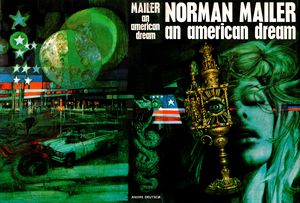

Cover of the British trade journal, The Bookseller, 26 December 1964, featuring the forthcoming British edition of An American Dream, published by Andre Deutsch.

-

Cover of Publishers’ Weekly featuring the forthcoming Dial Press version of An American Dream, 12 October 1964.

-

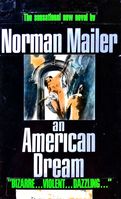

Cover of the third Dell paperback edition, published February 1970.

-

Paperback.

-

Paperback.

-

Chinese hardcover.

-

Vintage cover.

-

Harper cover.

-

“Major Reviews for a Major Novel” in the NYT.

-

Best seller list of the week in Publishers Weekly, May 1965, showing An American Dream in No. 6 position.

-

Announcement of Warner Brothers studios purchasing the movie rights to An American Dream, March 2, 1964

-

Advertising Copy for the New York Times, March 15, 1965

-

The New Republic April 3, 1965

Blurbs and Snippets

-

“I’ll finish my book in another year of bleeding at the typewriter,” Norman Mailer sighed at the Spindletop the other night. (1963)

-

Norman Mailer has just come into a large chunk of money. Dial, the book publishers, have given him a reported $125,000 for the rights to his as yet untitled and unwritten novel. . . . (1963)

-

Harper’s plan an anthology of Norman Mailer criticism.

-

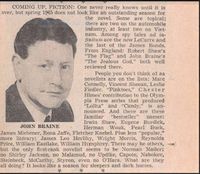

John Braine states that “the only first-rate novelist is Norman Mailer” publishing in 1965.

-

Norman Mailer’s An American Dream (Dial Press) is reviewed on the cover of the March 14th issue of Book Week by Tom Wolfe. . . . He is unique—there is no other word for Wolfe. . . . His essay on Mailer’s first novel in nine years is no exception. I think you will find it the most extraordinary review you’ve read in recent memory.

Letters

-

A 1965 letter from William Trotter in support of Mailer.

-

Mary Bancroft offers her strong support for Mailer in this 1965 letter.

-

Granville Hicks, in his review of Norman Mailer’s An American Dream [SR, March 20], tells us that Mailer’s main character has no reality, the other characters are “dummies,” the writing is sloppy, and the plot is absurd. One might say the same about Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground. Perhaps An American Dream is not a great book, but it is most certainly not a “bad joke.” It contains scenes of great power and pages of brilliant imagery. It holds one’s interest. It is an entertaining book to read. ~W. K. Mason, Madison, Wis.

-

In his letter to the Saturday Review (June 5, 1965), Bill Powers responds to criticism that An American Dream is a “literary hoax” and argues that through murder Rojack places himself “in the position to rebegin his life.”

Articles

-

William F. Buckley, Jr. states: “it was Mailer who developed the cult of the Hipster—the truly modern American who lets the bleary world go by doing whatever it bloody well likes, because nothing it does can upset the Hipsters’ inexhaustible Cool.” (The Miami Herald, September 26, 1965)

-

Lewis Nichols “In and Out of Books”

![Granville Hicks, in his review of Norman Mailer’s An American Dream [SR, March 20], tells us that Mailer’s main character has no reality, the other characters are “dummies,” the writing is sloppy, and the plot is absurd. One might say the same about Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground. Perhaps An American Dream is not a great book, but it is most certainly not a “bad joke.” It contains scenes of great power and pages of brilliant imagery. It holds one’s interest. It is an entertaining book to read. ~W. K. Mason, Madison, Wis.](/images/thumb/a/a1/19650417_Letter.jpg/157px-19650417_Letter.jpg)