The Mailer Review/Volume 3, 2009/Woman Redux: de Kooning, Mailer, and American Abstract Expression: Difference between revisions

(Fixes to apostrophes and quotation marks. Added references and additional text.) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

When I first read ''An American Dream'', the murder of Deborah, which opens the novel, mesmerized me with its bold and compelling intricacy, and I was starkly reminded of “Woman I,” a painting I first encountered as a college student. I wondered then, and still do, why people found the painting so troubling, for I found it strangely exhilarating. I felt the power of its counter-movements and the sense that this woman was alive and had broken her chains, bursting forth with her aliveness from all perspectives simultaneously, defying expectations and triumphing in the essence of her ugly beauty. So when I read ''An American Dream'' and encountered the opening murder sections and immediately thought of de Kooning’s “Woman I,” the association seemed valid given that Mailer’s descriptions of Deborah’s dead body mimic de Kooning’s iconoclastic work. | When I first read ''An American Dream'', the murder of Deborah, which opens the novel, mesmerized me with its bold and compelling intricacy, and I was starkly reminded of “Woman I,” a painting I first encountered as a college student. I wondered then, and still do, why people found the painting so troubling, for I found it strangely exhilarating. I felt the power of its counter-movements and the sense that this woman was alive and had broken her chains, bursting forth with her aliveness from all perspectives simultaneously, defying expectations and triumphing in the essence of her ugly beauty. So when I read ''An American Dream'' and encountered the opening murder sections and immediately thought of de Kooning’s “Woman I,” the association seemed valid given that Mailer’s descriptions of Deborah’s dead body mimic de Kooning’s iconoclastic work. | ||

"Look first at Deborah's face," Rojack's voice in his brain tells him as he then kneels "to turn her over." As she faces him now head on, he sees staring back at him "a beast." "Her teeth showed, the point of light in her eye was violent, and her mouth was open. It looked like a cave. I could hear some wind which reached down to the cellars of a sunless earth. A little line of spit came from the corner of her mouth, and an angle from her nose one green seed had floated its small distance on an abortive rill of blood" (39-40). | |||

Earlier, prior to his killing her, he had noticed the "mottling" of her skin that "spread in ugly smears and patches upon her neck, her shoulders, and what I could see of her breast. They radiated a detestation so palpable that my body began to race as if a foreign element, a poison altogether suffocating, were beginning to sweep through me." He begins to question: "Did you ever feel the malignity which rises from a swamp? It is real, I could swear it, and some whisper of ominous calm, that heavy air one breathes in the hours before a hurricane, now came to rest between us. I was afraid of her. She was not incapable of murdering me...She did not wish to tear the body, she was out to spoil the light, and in an epidemic of fear, as if her face--that wide mouth, full-fleshed nose, and pointed green eyes, pointed as arrows--would be my first view of eternity, as if she were ministering angel (ministering devil) I knelt beside her and tried to take her hand. It was soft now as a jellyfish, and almost as repugnant"(25-26). | |||

When Rojack later goes to view Deborah's body at the morgue, he admits: "I did not want to look at Deborah this time. I took no more than a glimpse when the sheet was laid back, and caught for that act a clear view of one green eye staring open, hard as marble, dead as the dead eye of a fish, and her poor face swollen, her beauty gone obese" (76). | |||

Mailer was clearly aware of painterly writing in the new expressionist manner as he references the "ultra-violet" lighting and green the color of guacamole, as in a painting by Vincent Van Gogh or Henri Rousseau. Indeed, Deborah's hallway wallpaper seems like a jungle background "conceived by Rousseau" with its "hot-house of flat velvet flowers, royal, sinister, cultivated in their twinings." They breathe at Rojack "from all four walls, upstairs and down" (13-14,21). The world looms large, all distorted, angular, pulpy and surreal. Rojack thinks: "There was something so sly at the center of her, some snake...guarding the cave which opened to the treasure" (34). He thinks about her own duality, good, evil, and then realizes: "But what I did not know was which of us imprisoned the other, and how? I might be the one who was...evil," he concludes, "and Deborah was trapped with me" (37). | |||

As Mailer questioned the idea of being imprisoned for both men and women, he faced down the feminists during the inflammatory 1960s and 1970s. I applaud his bravado when he recognized in The Prison of Sex that he is the fall guy in a world of one-liners that resists complex arguments. Although Hemingway faced down his fair share of criticism in his day, no one equals Mailer's fearlessness in speaking out for the primal purity of our sexual identities in love that cant, hypocrisy, and pretension smothers. He argues that "love is more stern than war" and that "people can win at love only when they are ready to lose everything they bring to it of ego, position, or identity." "Men and women can survive," Mailer states, "only if they reach the depths of their own sex down within themselves" (147). Part of that might well involve them slashing away at the phony, sniffling exteriors. Part of that might involve the hatchet approach that both de Kooning and Mailer implemented in their art to show how his delivery "over to the unknown" cannot happen when people assume stances rather than take risks. He concludes adamantly that the "physical love of men and women, insofar as it [is] untainted by civilization, [is] the salvation of us all" (140-41). But herein lies the rub and the essence of Mailer's beautiful artistic violence. Civilization taints love to the degree that pretence and dishonesty rule and to the degree that civilization fails to see the larger harmonious picture. | |||

"When you make love," Mailer said, "whatever is good in you or bad in you, goes out into someone else. I mean this literally. I'm not interested in the biochemistry of it, the electromagnetism of it, nor in how the psychic waves are passed back and forth, and what psychic waves are. All I know is that when one makes love, one changes a woman slightly and a woman changes you slightly...If one has the courage to think about every aspect of the act--I don't mean think mechanically about it, but if one is able to brood over the act, to dwell on it--then one is changed by the act. Even if one has been jangled by the act. Because in the act of restoring one's harmony, one has to encounter all the reasons one was jangled." In essence, he concludes, one needs to test oneself (Prisoner 189). | |||

Hemingway railed against the pretense and cant of his day, and he had what he called his "inborn shit detector." Mailer too could not shut up when things did not ring true, particularly as related to woman, and he found it ironic that people failed to recognize that his true thematic concern always was women--not all those heroes he seemed to write about. "Every theme he had ever considered," he said in Prisoner, "was ready to pass with profit through the question of women, their character, their destiny, their life as a class, their tyranny, their slavery, their liberation, their subjection to the wheel of nature, their root in eternity--no German metaphysician, no Doctor of Dialectics could have been happier at the thought of traveling far on the Woman Question." Furthermore, "He was forever pleased with himself at how cleverly he had buried this as yet undisclosed vision of women in his books" (20). He believed that, like D.H. Lawrence, he wrote with "the soul of a beautiful woman." "Whoever believes that such a leap is not possible across the gap, "that a man cannot write of a woman's soul, or a white man of a black man, does not believe in literature itself" (152). | |||

Or of the transformative power of art when it pushes beyond the boundaries. Art during the 1920S in Paris became, as Archibald MacLeish described it, a "conflagration," primarily because of the interdisciplinary convergence and explosion of all the arts. a similar phenomenon occurred in 1950s American in and around New York City and Provincetown, Massachusetts. Here the abstract expressionist painters such as de Kooning and the post -WWII writers such as Mailer mingled on the beach and in the bars as they redefined Modernism for a new era. They were aware of each other's work and influenced by a radicalism that dared, yet again, to upend realism and prosaic truths. Like all great art that might seek to discover an inner truth, they created works that would shock rather than soothe. De Kooning's "Woman I" rattled the art world with its violent distortions and ugly beauty. When I met Norman Mailer at his home in Provincetown in November, 2005, he readily acknowledged his awareness of de Kooning's "Woman I" painting. He went on to add, however, with a look of bemusement, "I never did like that painting. Do you?" As he looked me in the eyes, "Woman I" seemed to hang in the air between us as its own complicated and unspoken explanation. (1) | |||

. . . | . . . | ||

Revision as of 09:15, 22 June 2021

This page, “Woman Redux: de Kooning, Mailer, and American Abstract Expression,” is currently Under Construction. It was last revised by the editor KWilcox on 2021-06-22. We apologize for any inconvenience and hope to have the page completed soon. If you have a question or comment, please post a discussion thread. (Find out how to remove this banner.) |

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 9 Number 1 • 2015 • Maestro | » |

Linda Patterson Miller

Abstract: An examination of Norman Mailer’s appropriation of the painterly distortions of Willem de Kooning, a leading figure among the American Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s and 1960s in New York. Mailer’s portrait of Deborah Rojack’s murder in An American Dream bears uncanny parallels to de Kooning’s “Woman I,” a painting that Norman Mailer knew well by the time he was working on his novel. An examination of the two works in tandem illuminates how Mailer’s attempt, at least in this novel, was not to destroy women but to liberate them from within and to restore harmony for both men and women.

Note: I gave an earlier version of this essay at the Norman Mailer Conference in Provincetown, Massachusetts, November 3–5, 2005, at which time I was able to meet Mailer and ask him about his relationship to de Kooning’s work. I thank Phillip Sipiora for inviting me to speak at this conference and to become a part of the vibrant community of Norman Mailer Society members.

URL: https://prmlr.us/mr03mil

I am not a seasoned Norman Mailer scholar, even though his writing has captivated me since I first read him in college. Any more knowledgeable Mailer scholar who thinks I get him wrong might chalk it up to the distorting influence of Ernest Hemingway, that other white male who has commandeered a bid chunk of my scholarship. Actually, I recognize that both authors provoke passionate and intemperate reactions, sometimes from women, perhaps due to the public personas of these writers as hard-hitting, women-be-damned kinds of guys. Nonetheless, both these writers are quite similar in speaking directly to their times with art that shocks convention and galvanizes emotional truth. No person, male or female, who reads well either of these authors remains unaffected.

In order to arrive at artistic truth, Mailer tried to write “with the soul of a beautiful woman” as he, not unlike Hemingway, worked from the inside out.[1] This required radical action and innovative artistic techniques representative of the best and most transformative expressionist art. For Hemingway, that meant scrutinizing and then modeling his writing after the skewed perspectives and disjointed landscapes of Paul Cezanne, and for Mailer that meant appropriating for his art the erratic swirls and painterly distortions of Willem de Kooning, a leading figure among the American Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s and 1960s in New York. Following the publication of The Naked and the Dead, Mailer’s traditional war novel that brought him early fame in 1948, Mailer dared to experiment with unconventional literary forms and techniques so as to penetrate the post-WWII veneer of respectability and social and historical posturing. Mailer’s slash attack on American complacency and his use of distortion verged toward the irreverent and outlandish in his most shockingly powerful 1965 novel An American Dream. This work, sandwiched between Mailer’s war novel and his later autobiographical narratives forged in the school of new journalism, redefined expressionism for a post-WWII America. The novel unsettles and disorients as it defies conventional notions of gender, love, and artistic innovation. The writer of such a daredevil work should not be held at arms’ length, even by women.

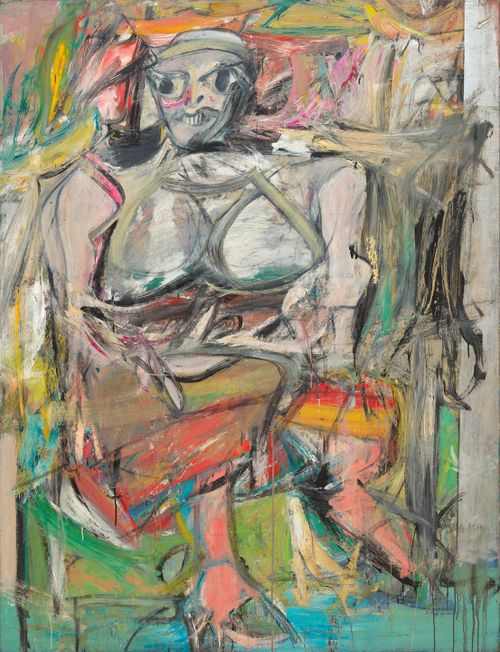

In order to discuss Mailer as a new expressionist who straddled realism and the surreal in creating a provocative and profound portrait of women, he is best aligned with another twentieth-century artist of Mailer’s time, Willem de Kooning, a painter who loved women even as he seemed to mutilate them on the canvas. De Kooning’s biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan regard de Kooning’s painting “Woman I,” which he worked on over the course of three difficult years, 1950–52, as “one of the most disturbing and storied” images of a woman in the history of art.[2] This painting marked a turning point for de Kooning, who clung to realism even as he yanked it free from formula, similar to Mailer.

Mailer’s portrait of Deborah Rojack’s murder in An American Dream bears uncanny parallels to de Kooning’s “Woman I,” a painting that Norman Mailer knew well by the time he was working on his novel. An examination of the two works in tandem illuminates how Mailer’s attempt, at least in this novel, was not to destroy women but to liberate them from within and to restore harmony for both men and women. I realize that my ideas here risk comparison to all those sick doctor jokes wherein the patient is told the good news that the doctors will be able to save her. The bad news is that to save her they must first kill her. Mailer recognized that Kate Millet, along with other feminists, believe that male writers love to kill off their heroines as aggressive acts of male superiority. Judith Fetterly never forgave Hemingway for killing Catherine Barkley in A Farewell to Arms, and Millet lashes out at D. H. Lawrence for his slaughter of a white woman at the hands of natives in “The Woman Who Rode Away.” As Mailer quotes her in The Prisoner of Sex, Millet says that “it is the perversion of sexuality into slaughter, indeed, the story’s very travesty and denial of sexuality, which accounts for its monstrous, even demented air.”[3]

Certainly Mailer’s no-holds-barred portrait of Deborah’s murder followed by Rojack’s “bitch of a brawl” with Ruta seems monstrous and even demented, as does the first “Woman” painting that de Kooning labored over for almost three years. He became increasingly slovenly with his personal hygiene and his studio space, and he often painted in the nude, obsessively creating and recreating his woman, slashing at the canvas, slathering on swabs of paint only to scrape it all off in order to start again. He had particular difficulty with her mouth and her hands, which seemed to him “clawlike.” Stevens and Swan describe de Kooning’s struggle to find “intimacy with an image; the broken, convulsive, and awkward must be conveyed, if the truth was to be served,” and the meanings were necessarily “contradictory.” “A mouth meant far more than a realistic depiction of two lips and a hole could reveal. A mouth was nourishment, smiles, frowns, sex, teeth, whispers, and shouts. It told lies and truths. It was inside and outside, a lipstick pose and a revelation. Viewed this way, a mouth was an almost impossible thing to get right.”[4]

When de Kooning began work on “Woman I,” and then his succeeding women paintings (almost all of them seated and facing full-frontal forward), he would face down the canvases without forethought. “Almost everyday he would use a sharpened spatula to scrape away most of the figure, flinging the dead paint onto newspapers strewn over the floor. (He would attack the picture in this way whenever the worked-over paint lost its freshness and became what he called ‘rotten’).”[5] He claimed at one point that he “always started out with the idea of a young person, a beautiful woman,” until he “noticed them change. Somebody would step out—a middle-aged woman. I didn’t mean to make them such monsters,” he said.[6]

“Woman I,” when exhibited in the early 1950s, unsettled its viewers, haunting them with its violent distortions, its palpable interior and exterior struggles. This woman, at odds with herself and her surroundings, grimaces grotesquely, her teeth sharply etched and protruding, her eyes dark blotches in white angular sockets. She seems trapped in a body that works against itself, arms and legs disproportionately skewed against a pea-green background that seems to have leeched through the canvas. Is she grinning or grimacing? Is she alive or dead or held captive behind invisible chains from which she struggles to break free?

When I first read An American Dream, the murder of Deborah, which opens the novel, mesmerized me with its bold and compelling intricacy, and I was starkly reminded of “Woman I,” a painting I first encountered as a college student. I wondered then, and still do, why people found the painting so troubling, for I found it strangely exhilarating. I felt the power of its counter-movements and the sense that this woman was alive and had broken her chains, bursting forth with her aliveness from all perspectives simultaneously, defying expectations and triumphing in the essence of her ugly beauty. So when I read An American Dream and encountered the opening murder sections and immediately thought of de Kooning’s “Woman I,” the association seemed valid given that Mailer’s descriptions of Deborah’s dead body mimic de Kooning’s iconoclastic work.

"Look first at Deborah's face," Rojack's voice in his brain tells him as he then kneels "to turn her over." As she faces him now head on, he sees staring back at him "a beast." "Her teeth showed, the point of light in her eye was violent, and her mouth was open. It looked like a cave. I could hear some wind which reached down to the cellars of a sunless earth. A little line of spit came from the corner of her mouth, and an angle from her nose one green seed had floated its small distance on an abortive rill of blood" (39-40).

Earlier, prior to his killing her, he had noticed the "mottling" of her skin that "spread in ugly smears and patches upon her neck, her shoulders, and what I could see of her breast. They radiated a detestation so palpable that my body began to race as if a foreign element, a poison altogether suffocating, were beginning to sweep through me." He begins to question: "Did you ever feel the malignity which rises from a swamp? It is real, I could swear it, and some whisper of ominous calm, that heavy air one breathes in the hours before a hurricane, now came to rest between us. I was afraid of her. She was not incapable of murdering me...She did not wish to tear the body, she was out to spoil the light, and in an epidemic of fear, as if her face--that wide mouth, full-fleshed nose, and pointed green eyes, pointed as arrows--would be my first view of eternity, as if she were ministering angel (ministering devil) I knelt beside her and tried to take her hand. It was soft now as a jellyfish, and almost as repugnant"(25-26).

When Rojack later goes to view Deborah's body at the morgue, he admits: "I did not want to look at Deborah this time. I took no more than a glimpse when the sheet was laid back, and caught for that act a clear view of one green eye staring open, hard as marble, dead as the dead eye of a fish, and her poor face swollen, her beauty gone obese" (76).

Mailer was clearly aware of painterly writing in the new expressionist manner as he references the "ultra-violet" lighting and green the color of guacamole, as in a painting by Vincent Van Gogh or Henri Rousseau. Indeed, Deborah's hallway wallpaper seems like a jungle background "conceived by Rousseau" with its "hot-house of flat velvet flowers, royal, sinister, cultivated in their twinings." They breathe at Rojack "from all four walls, upstairs and down" (13-14,21). The world looms large, all distorted, angular, pulpy and surreal. Rojack thinks: "There was something so sly at the center of her, some snake...guarding the cave which opened to the treasure" (34). He thinks about her own duality, good, evil, and then realizes: "But what I did not know was which of us imprisoned the other, and how? I might be the one who was...evil," he concludes, "and Deborah was trapped with me" (37).

As Mailer questioned the idea of being imprisoned for both men and women, he faced down the feminists during the inflammatory 1960s and 1970s. I applaud his bravado when he recognized in The Prison of Sex that he is the fall guy in a world of one-liners that resists complex arguments. Although Hemingway faced down his fair share of criticism in his day, no one equals Mailer's fearlessness in speaking out for the primal purity of our sexual identities in love that cant, hypocrisy, and pretension smothers. He argues that "love is more stern than war" and that "people can win at love only when they are ready to lose everything they bring to it of ego, position, or identity." "Men and women can survive," Mailer states, "only if they reach the depths of their own sex down within themselves" (147). Part of that might well involve them slashing away at the phony, sniffling exteriors. Part of that might involve the hatchet approach that both de Kooning and Mailer implemented in their art to show how his delivery "over to the unknown" cannot happen when people assume stances rather than take risks. He concludes adamantly that the "physical love of men and women, insofar as it [is] untainted by civilization, [is] the salvation of us all" (140-41). But herein lies the rub and the essence of Mailer's beautiful artistic violence. Civilization taints love to the degree that pretence and dishonesty rule and to the degree that civilization fails to see the larger harmonious picture.

"When you make love," Mailer said, "whatever is good in you or bad in you, goes out into someone else. I mean this literally. I'm not interested in the biochemistry of it, the electromagnetism of it, nor in how the psychic waves are passed back and forth, and what psychic waves are. All I know is that when one makes love, one changes a woman slightly and a woman changes you slightly...If one has the courage to think about every aspect of the act--I don't mean think mechanically about it, but if one is able to brood over the act, to dwell on it--then one is changed by the act. Even if one has been jangled by the act. Because in the act of restoring one's harmony, one has to encounter all the reasons one was jangled." In essence, he concludes, one needs to test oneself (Prisoner 189).

Hemingway railed against the pretense and cant of his day, and he had what he called his "inborn shit detector." Mailer too could not shut up when things did not ring true, particularly as related to woman, and he found it ironic that people failed to recognize that his true thematic concern always was women--not all those heroes he seemed to write about. "Every theme he had ever considered," he said in Prisoner, "was ready to pass with profit through the question of women, their character, their destiny, their life as a class, their tyranny, their slavery, their liberation, their subjection to the wheel of nature, their root in eternity--no German metaphysician, no Doctor of Dialectics could have been happier at the thought of traveling far on the Woman Question." Furthermore, "He was forever pleased with himself at how cleverly he had buried this as yet undisclosed vision of women in his books" (20). He believed that, like D.H. Lawrence, he wrote with "the soul of a beautiful woman." "Whoever believes that such a leap is not possible across the gap, "that a man cannot write of a woman's soul, or a white man of a black man, does not believe in literature itself" (152).

Or of the transformative power of art when it pushes beyond the boundaries. Art during the 1920S in Paris became, as Archibald MacLeish described it, a "conflagration," primarily because of the interdisciplinary convergence and explosion of all the arts. a similar phenomenon occurred in 1950s American in and around New York City and Provincetown, Massachusetts. Here the abstract expressionist painters such as de Kooning and the post -WWII writers such as Mailer mingled on the beach and in the bars as they redefined Modernism for a new era. They were aware of each other's work and influenced by a radicalism that dared, yet again, to upend realism and prosaic truths. Like all great art that might seek to discover an inner truth, they created works that would shock rather than soothe. De Kooning's "Woman I" rattled the art world with its violent distortions and ugly beauty. When I met Norman Mailer at his home in Provincetown in November, 2005, he readily acknowledged his awareness of de Kooning's "Woman I" painting. He went on to add, however, with a look of bemusement, "I never did like that painting. Do you?" As he looked me in the eyes, "Woman I" seemed to hang in the air between us as its own complicated and unspoken explanation. (1)

. . .

Citations

- ↑ Mailer 1971, p. 152.

- ↑ Stevens & Swann 2004, p. 309.

- ↑ Mailer 1971, p. 141.

- ↑ Stevens & Swann 2004, p. 323.

- ↑ Stevens & Swann 2004, p. 313.

- ↑ Stevens & Swann 2004, p. 311.

Works Cited

- Mailer, Norman (1965). An American Dream. New York: Dial.

- — (1971). The Prisoner of Sex. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Stevens, Mark; Swann, Annalyn (2004). De Kooning: An American Master. New York: Knopf.