The Mailer Review/Volume 7, 2013/An Executioner for a New Age

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 7 Number 1 • 2013 • A Double Life • Mind of an Outlaw | » |

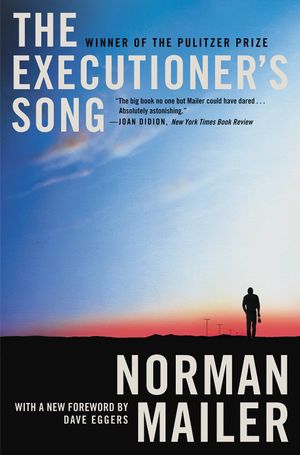

In these heady days of the ever-more-powerful Google search, it might seem odd that anyone would re-release an oversized 1100-page behemoth of a novel like The Executioner’s Song. Granted, this 2012 edition includes Mailer’s complete novel and afterword, a new foreword by Dave Eggers, several black-and-white photographs of Gilmore and some of the other important figures, and an appendix with snippets of Gilmore’s final letters, but for being such a weighty volume, it actually seems kind of light when compared to what Google can amass.

So why, I must ask, do we get another paper version of Norman Mailer’s 1979 Pulitzer-Prize winner on dead trees? Perhaps it’s due to the fact that ES might be Mailer’s magnum opus, Dostoyevskian in its scope, so the merits and importance of Mailer’s novel still resonate today. ES deserves our attention — particularly the “Americans” among us — so that we might gain some insight into the peaks and valleys of our humanity. In the wake of September 11, 2001, the interminable wars on drugs, poverty, and immigration, growing income inequality, the partisan and hyperbolic media landscape, gun violence at home, in movie theaters, and in schools, irrational clinging to 2nd Amendment rights, global climate change, and the subsequent atrocities committed in Iraq and Afghanistan by the US in the name of “freedom,” it seems America has embraced the song of the executioner, if not the tenor of Mailer’s novel. Eggers reminds us that with Gilmore’s execution, the US reinstated capital punishment and since 1977 executed over 1,000 more people in the name of justice (VIII). Echoing Eggers: we still seem to need Norman Mailer.

The Executioner’s Song speaks loudly with Mailer’s voice — not like his other Pulitzer-Prize novel The Armies of the Night published over a decade before in which “Norman Mailer” plays a central role — but the voice of the American man of letters whose interests and ambitions could not be demarcated by anything as simple as genre or medium. ES tells the story of Americans in what might be their own language, especially the women in “Western Voices”: language that seems as simple as a landscape, but that on closer scrutiny contains contrasts, subtleties, and shadows.

Mailer’s new language, one that Eggers discusses in his foreword, sublimates the “Norman Mailer” that had come before. The prose seems to reflect the story and its participants, not the author’s personality, as the reading public had come to expect from Mailer’s writing. He’s more Raymond Carver than the “Norman Mailer” of the sixties. It’s as if, Mike Lennon writes in a letter to The New York Times, Mailer tries to reinvent himself for a new generation — or at least a new America, post-Gilmore.

These are among the reasons that The Executioner’s Song continues to be relevant. A new edition of a classic is always welcome, and Eggers’ foreword emphasizes the importance of ES even to a generation who have likely never heard of Gary Mark Gilmore. He encourages a first reading with no foreknowledge of the events to get the most tension out of the narrative, suggesting that the foreword be returned to only after the novel has been read, if at all. New readers could get a pure experience, one that the original audience for ES could not have had, for even without a 24-hour news cycle, Gary Gilmore’s name was headline news for several months at the end of 1976 and the beginning of 1977. New readers would have no such context, isolated for the immediacy of the events, so they can experience them through the filter of Mailer’s narrative.

However, planted after page 320 are eight pages of photos that immediately remove the reader from the narrative and into history. While the photos are well chosen, anyone interested in the history would have resorted to Google long before page 320 for photos and videos of Gary, Nicole, Vern, Brenda; Gary’s drawings; and information about Utah, Mormonism, and even Mailer himself. Even with just a cursory search on Google Images, most of the included photos and drawings are easily found on the web, some in color which would have added an additional expense to a paper volume.

Perhaps my biggest issue with this new edition of The Executioner’s Song is more a criticism of the medium than it is of the content. Since the introduction of the Amazon Kindle in 2007, ebooks sales have grown while the sale of print books have declined. In 2011, Amazon announced that the sales of ebooks have overtaken print books, and the trend seems likely to continue. While this statistic might seem to be the print market’s swan song, according to The Guardian, the ebook market has actually produced a “renaissance of reading” that also increases the sale of print books. However, since these 2011 figures, sales of ebooks have fallen, attesting that the print book might have a longer life.

Regardless of how we view ebooks and the technology that supports them — we all know how Mailer himself felt about digital technology — the digital is here to stay. So far in their short life, most ebooks only mimic the print book, like the Kindle version of The Executioner’s Song, and they have little appeal for Mailer enthusiasts, including yours truly. However, with tablet computers like the iPad and the various flavors of Android getting cheaper and more capable, the ebook will begin to evolve into something only remotely related to the print book. For now, even our realization of the ebook is directed by our conception of the book in its printed form: i.e., on atoms. When we truly begin to think digitally, we will realize the power of the bit. It’s likely that The Executioner’s Song will remain in print for years to come and become an even more valuable but nostalgic artifact. A truly new edition would be digital, maybe The Executioner’s Song (v. 2.0).

As the 2012 edition of The Executioner’s Song makes clear, Mailer’s novel is suffused with history. However, since Mailer’s novel is so large in print, it leaves little room for much history. An ebook has no such limitation. It could include photographs, video, newspaper articles, interviews, sound clips, letters, eyewitness accounts, scenes from Schiller’s film, and anything else that could be digitized, all linked to the sections of the novel to which they pertain, like digital annotations. Additionally, articles and discussion related to Mailer and his novel could also be included. Currently, companies like Apple and Inkling are beginning to think digitally and push toward this true ebook, one that’s not limited by a nostalgic medium on dead trees, but that has no physical boundaries to restrict its content.

Of course, as Eggers so wisely reminds us, Mailer’s novel should take the forefront: there should be a convenient way to switch off the digital annotations so readers could still experience The Executioner’s Song as Mailer wrote it. If they so desire. We could still have the pure experience of Mailer’s novel without the distractions of history or fact.

Since their invention, books have been convenient containers for ideas and stories. They hold human understanding between two covers, allowing us to order our experience through the filters of another’s perspective. The author (or editor) serves as the curator of ideas and awareness. What he or she chooses to include (and exclude) in a book shapes our estimation of the subject, thus shaping our reality — our truth. If a novel is to stand the test of time, its story must continue to remain relevant to the experiences of subsequent generations.

In the digital world, the job of the curator becomes paramount.

In a way, Norman Mailer’s voice is clearest when he is acting in this role. While his voice might change, his serious work decides what gets displayed and what gets discarded. Between tweets, blog posts, Facebook updates, Pinterest pins, YouTube video snippets, and Podcasts adding to the official streams of news and entertainment, the role of the artist (and educator) in the digital age is one of curator: the trusted personality that helps us select the best materials through which to order our lives.

We live in a time, despite all of its drawbacks and weaknesses, still influenced by the artist’s authority. While this paradigm may be shifting, new versions of important novels seem to bring us some stability, especially as large, weighty paper volumes. This newest edition of The Executioner’s Song is no exception, even if it presages an imminent (inevitable?) digital volume in the foreseeable future.