The White Negro/1

| 57.1 | 59.8a | The White Negro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Bibliography |

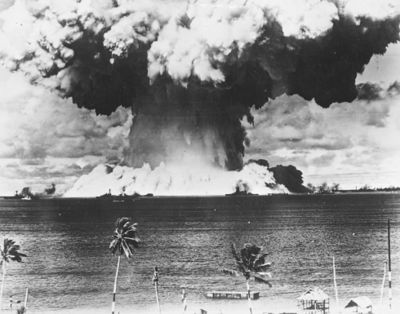

Probably, we will never be able to determine the psychic havoc[1] of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years. For the first time in civilized history, perhaps for the first time in all of history, we have been forced to live with the suppressed knowledge that the smallest facets of our personality or the most minor projection of our ideas, or indeed the absence of ideas and the absence of personality could mean equally well that we might still be doomed to die as a cipher in some vast statistical operation in which our teeth would he counted, and our hair would be saved, but our death itself would be unknown, unhonored, and unremarked, a death which could not follow with dignity as a possible consequence to serious actions we had chosen, but rather a death by deus ex machina in a gas chamber or a radioactive city;[2] and so if in the midst of civilization — that civilization founded upon the Faustian[3] urge to dominate nature[4] by mastering time, mastering the links of social cause and effect — in the middle of an economic civilization founded upon the confidence that time could indeed he subjected to our will, our psyche was subjected itself to the intolerable anxiety that death being causeless, life was causeless as well, and time deprived of cause and effect had come to a stop.[5]

The Second World War presented a mirror to the human condition which blinded anyone who looked into it. For if tens of millions were killed in concentration camps out of the inexorable agonies and contractions of super-states founded upon the always insoluble contradictions of injustice, one was then obliged also to see that no matter how crippled and perverted an image of man was the society he had created,[6] it wits nonetheless his creation, his collective creation (at least his collective creation from the past) and if society was so murderous, then who could ignore the most hideous of questions about his own nature?[7]

Worse. One could hardly maintain the courage to be individual, to speak with one’s own voice, for the years in which one could complacently accept oneself as part of an elite by being a radical were forever gone. A man knew that when he dissented, he gave a note upon his life which could be called in any year of overt crisis. No wonder then that these have been the years of conformity and depression. A stench of fear has come out of every pore of American life, and we suffer from a collective failure of nerve. The only courage, with rare exceptions, that we have been witness to, has been the isolated courage of isolated people.[8]

Notes

- ↑ The psychological, specifically the unconscious. Mailer was writing at a time when artists and intellectuals were immersed by Sigmund Freud’s theories the unconscious, repression, and neuroses.

- ↑ Mailer here is referring to the millions of deaths due to concentration camps and atomic weapons during WWII, deaths which in many cases were anonymous, but more importantly, deaths which occurred not as a result of the actions individuals had committed to cause their own deaths, but death by deus ex machina (God from the machine), mass, mechanized, and impersonal death.

- ↑ “Faustian” alludes to the legendary character Dr. Faust or Faustus who made a deal with the devil to trade his soul in exchange for knowledge.

- ↑ This is the drive in Western civilization to master time through science and technology, an impulse that resulted in the creation of nuclear weapons.

- ↑ Mailer also makes the existential argument here that “death being causeless,” again, not resulting from our own actions, “life was causeless as well,” or to put it another way, if death had lost meaning, perhaps life had lost meaning too. What was one’s life if it could be so suddenly and causelessly extinguished? Mailer speaks to a prevalent anxiety here that life had become absurd, and those with a heightened awareness of this state of affairs found themselves confronting an existential void.

- ↑ Mailer’s point is actually pretty simple. Societies are the products of the individuals who created them, but individuals are in turn the products of the societies in which they live. This observation is the basic premise of sociology, that we are the products of the combined forces of institutions like family, school, church, mass media and culture, not to mention economic forces like capitalism.

- ↑ Mailer’s logic leads then to this inescapable conclusion, phrased here as a rhetorical question. A fundamental part of Mailer’s argument is that the Hipster is an individual who has recognized the darker forces within his own unconsciousness, what Carl Jung called the shadow self, the self that many choose to repress because facing their darker selves can be uncomfortable, even frightening. Jung believed, however, that a person needs to integrate the darker self with the ego in order to achieve a sense of wholeness.

- ↑ Mailer addresses here the drive toward conformity and adjustment to the status quo which characterized the Cold War era and which he and other members of the Beat Generation found intolerable.