Preface to Discriminations

Dwight Macdonald was not like other literary men, and yet it is the perfect contradiction to all the paradoxes of his personality that no one ever was more. Other literary critics may have been as learned (although but a few) and one or two like Lionel Trilling may have written in as impressive a style as Dwight, and certainly any number gave fine literary parties although I cannot think of one of us over the years who gave as many where writers and intellectuals could meet and — would wonders never cease — something would actually happen. As a host, Dwight and both his wives, Nancy, and most certainly Gloria helped him to give parties as full of quirks as his own charm. When you went to his house, you never knew if the evening would end in an acrimonious debate between two intellectual figures who might on the occasion not speak well of one another again for years, or whether you would hear or learn something you never knew before, or whether you would just get drunk, meet a good woman, and have a good time. His were the only literary parties I know where you could count on something flirtatious — a rose hue, so to speak — stealing into the salon.

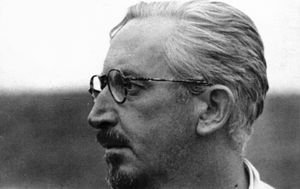

So much of that was due to Dwight. His contradictions were not only his person, but his ongoing energy and delight. I think he took considerable secret pride in the variety of his facets. I always suspected at Dwight knew as well as any of us how saintly he could be, how clown-like, how human, how damnably prejudiced. He was a radical, he was a conservative, he was compassionate, he was scathing; he was fierce, he was a pacifist; he was a very handsome man, he also had a huge gawking ungainly body and a potbelly; he had exquisite taste in many a literary matter, and yet could be wholly insensitive to all kinds of strange new merits — which is why I think his fling as a film critic leaves few memories — but his transcendental virtue, that unique quality which sets him far apart from all other literary figures for whom one can feel respect, was that he had the rare gift of always speaking out of his own voice.

Since he was also a prodigious reader who rarely forgot a word, time in his company offered a monumental paradox: you encountered a man who lived with something like the formidable culture of an Edmund Wilson yet could think and speak aloud with all the candor, unselfconsciousness and pleasure in the moment that we associate with writers so ineluctably spontaneous as Jack Kerouac. The greatest thing about Dwight was that you could win an argument with him — indeed, I think he hardly cared who had the last word. It was more important that the line of the discussion be lively. It would delight him, I believe, to lose a discussion on a topic he had won many times before. There was something in his quintessentially dialectical spirit that distrusted sure things. So if the inexorable logic of his verbal polemic was broken by an unexpected point made by his opponent, he had the rare generosity to seize on the new point with as much pleasure as if he had come up with it himself. It is for that reason, I believe, that he was so very good as a writer. I have gone on at length about his social and personal gifts because when all is said, how many of us could ever equal his charm, but I would not wish to suggest that the man was worth more than his work. Dwight gave us no great body of books,[2] and spent his talents in writing some of the better political and literary criticism of our time, but more important than his oeuvre was his influence. He was one of the best teachers of writing in the world. He gave no classes, but if one had learned a little about writing already, well, then there was all the world of self-expression to pick up in the felicities of his style. Dwight had something fabulous to teach. It was to look to the feel of the phenomenon. Describe what you see as it impinges on the sum of your passions and your intellectual attainments. Bring to the act of writing all of your craft, care, devotion, lack of humbug and honesty of sentiment. And then write without looking over your shoulder for the literary police. Write as if your life depended on saying what you felt as clearly as you could while never losing sight of the phenomenon to be described. If something feels bad to you, it is bad: Others had received the same message from Hemingway, but it took Dwight Macdonald to give the hint to many a young writer and intellectual that the clue to new discovery rests not so much on the idea with which you begin as in the style of your attack upon the problem. Dwight attacked every subject upon which he wrote with all the angelic candor of his strengths and weaknesses and so introduced a new note into our intellectual letters, for he never let us forget that when an idea attacks another idea we are near to the totalitarian, but when a man explores a subject with all his wit and all his flaws, then indeed we know more, yes, so much more. Three cheers for Dwight Macdonald then, I say, but softly, for I would not wish to embarrass him. He loved books too much for any of us to make a loud sound in the library.

— NORMAN MAILER

New York, November 1983

Citation

- ↑ From Macdonald, Dwight (1983). Discriminations: Essays and Afterthoughts. Da Capo Press. Reprinted by Project Mailer with permission of the estate of Norman Mailer. (83.57)

- ↑ His best known work may have been contained in his essays for Politics, and his book Memoirs of a Revolutionist. [Mailer's note.]