The Mailer Review/Volume 1, 2007/Mailer Takes on America: Images from the Ransom Center Archive

| « | The Mailer Review • Volume 1 Number 1 • 2007 • Inaugural Issue | » |

Cathy Henderson

Richard W. Oram

Molly Schwartzburg

Molly Hardy

URL: https://prmlr.us/mr01hen

In May 2005, the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, announced the acquisition of the entire Norman Mailer archive. In response to the question “Why Texas?” Mailer commented,

| “ | the major part of my decision (and pleasure) to have this archive go to the Ransom Center is that you have one of the best, if not, indeed, the greatest collection of literary archives to be found in America. What the hell. Since it’s going to Texas, let’s say one of the best in the world. | ” |

Since then, a team of four archivists has been hard at work organizing and cataloging the 900 (give or take a few) document boxes worth of material chronicling every phase of Mailer’s life and career from the 1930s on. The archive will open for use at the beginning of 2008.

Because of widespread public interest in the acquisition, Thomas F. Staley, the Center’s Director, asked that the authors of this article mount an exhibition based on the archive in the fall of 2006. We therefore had the challenge of encountering the Mailer papers in their “raw” unprocessed state, in the original folders and cartons. For those of us who savor the experience of handling original documents largely untouched since their creation, it was also a privilege. The exhibition could not have come together without the considerable assistance of J. Michael Lennon, Mailer’s unofficial archivist, who knows these papers better than anyone.

“Norman Mailer Takes on America” placed Mailer and his works in a political and cultural context and traced the central role he has played in our awareness and understanding of what critic Morris Dickstein has called the “shocks of history, politics and contemporary life” that shaped the latter half of the twentieth century and continue to unsettle the twenty-first. The exhibition was the public’s first opportunity to sample the Mailer archive and more than 200 items spanning the full range of Mailer’s career, examined in the context of the cultural and historical events that sparked his imagination. With this pictorial essay excerpted from the full exhibition, the curators hope to convey a small sense of its scope for those who were unable to view it in Austin.[a]

-

A 1939 form letter from the Dean of Freshman at Harvard College asks Mailer’s father to comment on his son’s preparedness for higher education.

-

Isaac Mailer lists loyalty, fairness, and sincerity among his son’s qualities and sees early signs of his adult son’s love of the limelight.

-

“The Greatest Thing in the World” was Mailer’s first story published in the Harvard Advocate. It won the prestigious College Short Story Contest in 1941 and helped convince Mailer’s family that he might indeed be able to pursue a successful career as a writer.

-

A snapshot of Norman Mailer, ca. 1944–1945, taken while stationed in Japan. This photograph was probably sent to him by another soldier, Ralph A. DiLella (“Me”).

-

A letter from John Dos Passos to Mailer, 8 September 1948, in which Dos Passos compliments the young novelist for The Naked and the Dead and singles out the core element of Mailer’s first novel: “every time has its theme and in attacking the problem of power you aimed at the central theme of our time.”[b]

-

The journal that Mailer kept briefly in the early 1950s reveals much about his early days in Greenwich Village. As this entry (14 January 1952) shows, Mailer was formulating a vocabulary of violent rebellion years before he fully articulated the concept of the underground in “The White Negro.” The text also gives a glimpse into Mailer’s early relationship with his second wife, Adele.

-

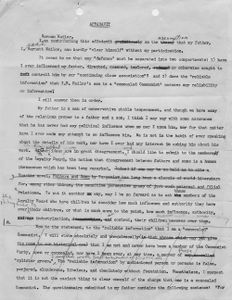

In 1952, Isaac Mailer was called to appear before the U.S. Civil Service Commission’s loyalty board because of his association with his son, “who is reported to be a concealed Communist.” This draft of the letter Mailer and his lawyer prepared and submitted to the commission has Mailer’s corrections in pencil. Mailer’s father was ultimately cleared without a hearing.

-

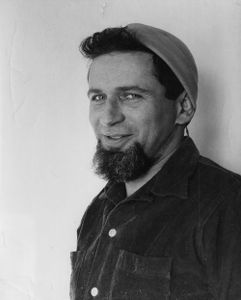

This photograph (ca. 1957) offers a rare glimpse of the hipster goatee Mailer sported for just a few months in the late 1950s.

-

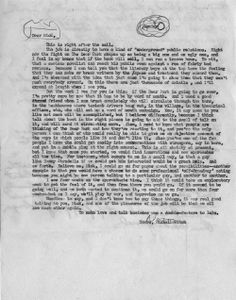

Mailer asks his close friend Mickey Knox to help him create “buzz” for The Deer Park. His view was “that a serious novelist can reach his public even against a run of fairly bad reviews” by having friends “circulate through the bars, in the hashhouses where the taxicab drivers hang out, in the village, in the theatrical offices, etc. who will set up a word of mouth campaign.”

-

In October 1960, Allen Ginsberg wrote to Mailer asking him to defend the literary value of William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch. The first two sentences of Mailer’s response appear as part of a blurb on the back jacket cover of the Grove Press edition of the novel. A month later, Mailer gave a statement in court defending the novel’s honest portrait of America’s “own potential Hell” of “monsters, half-mad geniuses, cripples, mountebanks, criminals, perverts, and putrefying beasts.”

-

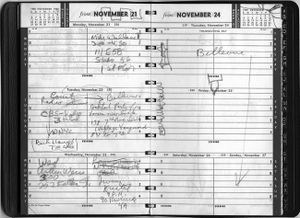

Several days after he stabbed his wife, Adele, in the early morning hours of 20 November 1960, Mailer was committed to Bellevue Hospital for observation. The entries in his appointment book for the week of November 21–27 include an interview with Mike Wallace a few days before Mailer entered Bellevue.

-

In “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” Mailer perceptively analyzed Kennedy’s cult of personality, his function as an “existential hero” who could satisfy a bored country’s need for a mythic figure. Esquire editor Arnold Gingrich had changed the last words of the title from “Supermarket” to “Supermart,” a revision to which Mailer vehemently objected. The breach healed, and Mailer went on to become one of the magazine’s big draws.

-

In September 1962, Mailer and William F. Buckley Jr. met in Chicago in an evening billed as a debate between a hipster and a conservative. When Buckley asked, “Are you prepared to say that it is distinctly the right that wants to win the cold war?” Mailer shouted back, “No it is the right wing that wishes to blow up the earth.” His notes, taken after the Buckley-Gore Vidal debate on the David Susskind show in the same month, continue in the same vein: “[Buckley] has had the advantage of preaching conservatism in a country which has fed on nothing for its mind but the intellectual concentration camps of anti-Communism, anti-Communism, and more anti-Communism for so long that it is impossible to address an American audience on politics without proving to one’s [illegible] that a half of one’s audience is made up of apes. Look around you, my friends.”

-

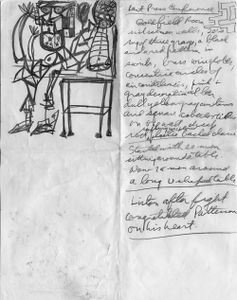

Mailer’s notes for the Sonny Liston-Floyd Patterson rematch in Las Vegas on 22 July 1963. Mailer had covered the earlier Liston-Patterson fight and wrote about it in the seminal essay “Ten Thousand Words a Minute.”

-

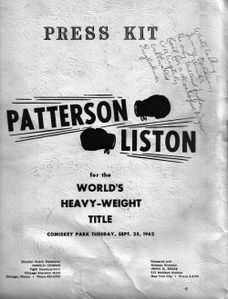

Mailer covered the first (1962) Patterson-Liston fight in Chicago for Esquire. James Baldwin also reported on the match, and in “Ten Thousand Words a Minute,” Mailer describes a “bad feeling” between them at Comiskey Park. After one of their meetings, he scribbled a note to himself on his press packet: “While talking to Jimmy Baldwin, I think: the only true and proper foil for a developed Negro is a highly cultivated Englishman.” In a notebook from the same period, Mailer changed “cultivated Englishman” to “Limey.”

-

A Mailer notebook from the early 1960s describes an early (and amicable) meeting between the two pioneers of “the New Journalism,” who were far too different in personality and outlook to become close friends.

-

Packed with information about Mailer’s relationship with Robert Lowell, this November 1963 postcard alludes both to their first meeting in the late 1940s and to Lowell’s admiration for Mailer’s journalism and (somewhat surprisingly) his poetry. The poet’s qualified endorsement of Mailer as “often the first journalist in America (U.S. America)” looks forward to their exchange in The Armies of the Night. The Ransom Center also owns a substantial Lowell archive.[c]

-

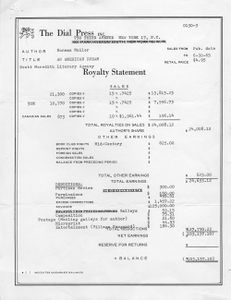

Mailer received an unusually large advance of $125,000 for An American Dream, originally serialized in Esquire and published as a book in March 1965. His aggressive new agent Scott Meredith was largely responsible for this, and the deal ushered in an era of big-money sales for major American novelists.

-

The antiwar activist Jerry Rubin invited Mailer, as a “spokesman for our generation,” to speak at the Vietnam Day rally at Berkeley on 21 May 1965, attended by over 30,000 people. Rubin and Abbie Hoffman regarded Mailer as a mentor who had given them “permission to insult a father figure [i.e., Lyndon Johnson].”

-

Eldridge Cleaver wrote this letter of thanks in 1966, toward the end of his second incarceration at Soledad Prison. Cleaver later attacked James Baldwin for his condemnation of Mailer’s “The White Negro.” For his part, Mailer concluded that he would not vote in the 1968 election — unless it was for Cleaver.

-

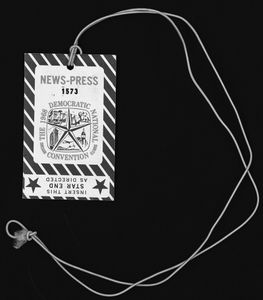

Mailer’s press pass from the 1968 Democratic National Convention at Chicago, which he covered for Harper’s Magazine. Mailer was sympathetic to the Yippies and other radicals, the descendants of the fifties hipsters, who gathered in the streets to resist the police. Yet Mailer had a surprisingly low opinion of the violent tactics and the political naïveté of the antiwar movement.

-

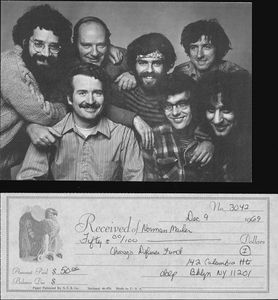

A greeting card from the Committee to Defend the Conspiracy, ca. 1969, and Mailer’s contribution receipt. Mailer disagreed with the Yippie movement’s tactics in Chicago but protested the Chicago Seven’s indictment and trial on federal charges of conspiracy and inciting to riot. In 1969, he famously testified, “left-wingers are incapable of conspiracy because they’re all egomaniacs.” The trial, widely regarded as an historic clash between the forces of convention and radicalism, ended in five convictions, all of which were reversed.

-

Willie Morris, the energetic young editor of Harper’s, devoted the entire March 1968 issue of the magazine to Mailer’s “The Steps of the Pentagon,” which later became The Armies of the Night. Morris’s gamble in publishing what was then the longest essay ever to appear in a periodical paid off handsomely, as he acknowledged in this September 1968 letter.[d]

-

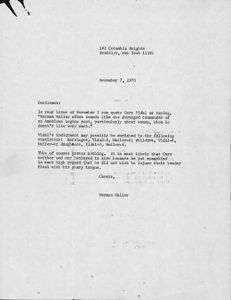

This 1970 letter to Women’s Wear Daily responds to an article by Gore Vidal concerning Mailer’s views on women. The simmering disagreement between the two writers continued for the next decade in print, in person, and on television. Later, they would appear together at the 1985 PEN Symposium and in Shaw’s Don Juan in Hell, with Vidal as the Devil and Mailer as Don Juan.

-

Jack Henry Abbott’s letter to Mailer, 8 December 1978. Abbott was a career criminal with a literary bent who first contacted Mailer while Mailer was working on The Executioner's Song. Mailer began a long-running correspondence with him about In the Belly of the Beast, Abbott’s collection of essays, as well as prison life and penal reform. The voluminous Mailer-Abbott correspondence is supplemented by an intriguing letter from Abbott to Mailer biographer Hilary Mills Loomis concerning Abbott’s ambivalent feelings toward his mentor.

-

[Page 1] A letter from Don DeLillo to Norman Mailer, 20 September 1991, about Harlot's Ghost.

-

[Page 2] DeLillo considers it Mailer’s most “adroit” book and praises, among other qualities, Mailer’s skill in making “a welcoming object of a book out of all the rotten karma and bad medicine of the decades” it chronicles.[e]

-

[Page 1] This sympathetic exchange reveals Norman Mailer and Don DeLillo’s shared fascination with Lee Harvey Oswald. As DeLillo writes, “We’re all stuck with this guy, you and I more than most.”

-

[Page 2] The two writers approach the Kennedy assassination from very different angles in their books — Mailer’s Oswald’s Tale and DeLillo’s Libra.

-

[Page 1] DeLillo puts particular emphasis on issues of privacy, surveillance, and paranoia, while Mailer focuses upon his own continually developing understanding of the facts of the case.

-

[Page 2]

Notes

- ↑ Images of Norman Mailer’s unpublished works and letters are published with Mr. Mailer’s permission. Copyright © 2007 by Norman Mailer. Images of materials from the Mailer Archive are published with the permission of the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- ↑ Published with the permission of Lucy Dos Passos Coggin.

- ↑ Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC on behalf of the Robert Lowell Estate. Copyright © 2005 by Harriet Lowell and Sheridan Lowell.

- ↑ Published with the permission of David Rae Morris and JoAnne Prichard Morris.

- ↑ Don DeLillo’s letters published with the permission of Mr. DeLillo.

![A letter from John Dos Passos to Mailer, 8 September 1948, in which Dos Passos compliments the young novelist for The Naked and the Dead and singles out the core element of Mailer’s first novel: “every time has its theme and in attacking the problem of power you aimed at the central theme of our time.”[b]](/images/thumb/a/a1/HRC-Archive-03.jpg/233px-HRC-Archive-03.jpg)

![In September 1962, Mailer and William F. Buckley Jr. met in Chicago in an evening billed as a debate between a hipster and a conservative. When Buckley asked, “Are you prepared to say that it is distinctly the right that wants to win the cold war?” Mailer shouted back, “No it is the right wing that wishes to blow up the earth.” His notes, taken after the Buckley-Gore Vidal debate on the David Susskind show in the same month, continue in the same vein: “[Buckley] has had the advantage of preaching conservatism in a country which has fed on nothing for its mind but the intellectual concentration camps of anti-Communism, anti-Communism, and more anti-Communism for so long that it is impossible to address an American audience on politics without proving to one’s [illegible] that a half of one’s audience is made up of apes. Look around you, my friends.”](/images/thumb/1/18/HRC-Archive-24.jpg/246px-HRC-Archive-24.jpg)

![Packed with information about Mailer’s relationship with Robert Lowell, this November 1963 postcard alludes both to their first meeting in the late 1940s and to Lowell’s admiration for Mailer’s journalism and (somewhat surprisingly) his poetry. The poet’s qualified endorsement of Mailer as “often the first journalist in America (U.S. America)” looks forward to their exchange in The Armies of the Night. The Ransom Center also owns a substantial Lowell archive.[c]](/images/thumb/6/6a/HRC-Archive-21.jpg/300px-HRC-Archive-21.jpg)

![The antiwar activist Jerry Rubin invited Mailer, as a “spokesman for our generation,” to speak at the Vietnam Day rally at Berkeley on 21 May 1965, attended by over 30,000 people. Rubin and Abbie Hoffman regarded Mailer as a mentor who had given them “permission to insult a father figure [i.e., Lyndon Johnson].”](/images/thumb/b/b9/HRC-Archive-28.jpg/300px-HRC-Archive-28.jpg)

![Willie Morris, the energetic young editor of Harper’s, devoted the entire March 1968 issue of the magazine to Mailer’s “The Steps of the Pentagon,” which later became The Armies of the Night. Morris’s gamble in publishing what was then the longest essay ever to appear in a periodical paid off handsomely, as he acknowledged in this September 1968 letter.[d]](/images/thumb/4/4e/HRC-Archive-11.jpg/205px-HRC-Archive-11.jpg)

![[Page 1] A letter from Don DeLillo to Norman Mailer, 20 September 1991, about Harlot's Ghost.](/images/thumb/8/8d/HRC-Archive-12.jpg/229px-HRC-Archive-12.jpg)

![[Page 2] DeLillo considers it Mailer’s most “adroit” book and praises, among other qualities, Mailer’s skill in making “a welcoming object of a book out of all the rotten karma and bad medicine of the decades” it chronicles.[e]](/images/thumb/5/53/HRC-Archive-13.jpg/229px-HRC-Archive-13.jpg)

![[Page 1] This sympathetic exchange reveals Norman Mailer and Don DeLillo’s shared fascination with Lee Harvey Oswald. As DeLillo writes, “We’re all stuck with this guy, you and I more than most.”](/images/thumb/c/c2/HRC-Archive-23.jpg/217px-HRC-Archive-23.jpg)

![[Page 2] The two writers approach the Kennedy assassination from very different angles in their books — Mailer’s Oswald’s Tale and DeLillo’s Libra.](/images/thumb/3/3b/HRC-Archive-22.jpg/215px-HRC-Archive-22.jpg)

![[Page 1] DeLillo puts particular emphasis on issues of privacy, surveillance, and paranoia, while Mailer focuses upon his own continually developing understanding of the facts of the case.](/images/thumb/5/55/HRC-Archive-18.jpg/231px-HRC-Archive-18.jpg)

![[Page 2]](/images/thumb/e/e6/HRC-Archive-27.jpg/232px-HRC-Archive-27.jpg)