Foreword to St. Patrick’s Day with Mayor Daley: Difference between revisions

(Created page.) |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 14:05, 21 December 2018

If one of the cruelest remarks in the language is: Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach, its parallel must be: Those who encounter experience, learn to live; those who don’t, write.

The second remark has as much truth as the first — which is to say, some truth. Of course, many a young man has gotten himself into danger out of the desire to pick up material for his writing, but as a practical matter (a matter to make one wistful) no major or minor American athlete, politician, engineer, trade union official, surgeon, airline pilot, bullfighter, chess master, call girl, sea captain, teacher, bureaucrat, mafioso, pimp, recidivist, lawyer, physicist, rabbi, clergyman or priest seems to have also emerged as a good writer.

The remark is too comprehensive; a few have. Gene McCarthy is a decent poet, Charles Rembar writes very well for a lawyer, Malcolm Braley and Eldridge Cleaver are talented writers, Major Collins is excellent for an astronaut, and so is Jim Bouton for a ball player. What with ghost-writers, collaborators, and editors hand-cranking the tongues of less-illuminated famous men long enough to get their memoirs into tape recorders, it could be said that some dim reflection can be found in literature of the long aisles and huge machines of that social mill which is the world of endeavor, yes, just about as much as comes back to us from a very old piece of film insufficiently exposed in the picture-taking. A ghost image with the faintest coating of silver crystals has been substituted for the original lights and deep shadows of the object. So, for every good novel about a trade union that has been written from the inside, we have ten thousand better novels to read about authors and the damnable social activities of their friends. Writers tend to live with writers just as automotive engineers congregate in the same country clubs of the same suburbs around Detroit.

But even as we pay for the social insularity of Detroit engineers by having to look at the repetitive hump of their design until finally what is most amazing about the automobile is how little it has been improved, so literature suffers from its own endemic hollow: we are over-familiar with the sensitivity of the sensitive and relatively ignorant of the cunning of the strong and the stupid, one — it may be fatal — step removed from good and intimate perception of the inside procedures of the corporate, financial, governmental, Mafia and working-class establishment. Investigative journalism has taken us into the guts of the machine, only not really, not enough — we still do not have much idea of the soul of any inside operator — we do not, for instance, yet have a clue to what makes a quarterback ready for a good day or a bad one. In addition, the best investigative reporting of new journalism tends to rest on too narrow an ideological base — the rational, ironic, fact-oriented world of the media liberal, so we have a situation, call it a cultural malady, of the most basic sort — a failure of sufficient real literary information (that is, good literary information) to put into those centers of our mind we use for assessment. No matter how much we read, we tend to know too little of how the world works. The men who do the work offer us no real writing, and the writers who explore the minds of such men approach from an intellectual stance which distorts their vision. You would not necessarily want a saint to try to write about a computer engineer, but you certainly would not search for the reverse. All too many saints, monsters, maniacs, mystics and rock performers are being written about these days, however, by practitioners of journalism whose inner vision could be laid out by rational maxims (like: what’s his angle?) sufficiently constant to be fed into a computer. Our continuing inability to comprehend the world makes certain to continue.

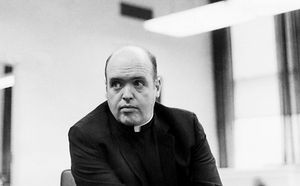

Now we have here a book which offers its modest antidote. It is a set of pieces about various personalities, saintly and profane, and its point of view is Catholic, subtly devout. Yet it is incontestably a collection of pieces written in the spirit of new journalism. The personality of the author is avowedly the instrument by which these personages are viewed, and he is a Maryknoll priest, a man of 47 whose working life has been spent in the priesthood. He has nonetheless managed to become a good writer.

There is for a priest nothing automatic about that. Intelligence is not enough to make a good writer. Indeed, most of the intelligent men and of the world have an instinctive aversion to displaying too much of themselves on a page — writing is, after all, an act to freeze and fix every part of our psyche which rests on caution: we are exposing ourselves, willy-nilly in a void. We are writing into a sea of invisible faces — we will not know their expressions as they read our words. So there is something irresponsible, even wild, in showing oneself on the page — who knows what can come back? That is one well-grounded inhibition against becoming a writer. For a priest, there are others. Priests are brought by training, at least if they are Father Kennedy’s age, to believe more in the responsibilities, even the duty, of their language than in its originality. A priest is not supposed to be innovative so much as obedient to principles instructed to him from without, from above.

Such a remark ignores, of course, the changes taking place in the Catholic Church, the seismographic shifts of its modem standing on such matters as celibacy and Communism, but then we are not speaking of young priests entering today’s seminaries now filled with every intellectual ferment of the modem world, we are speaking of the early Fifties when Eisenhower was in flower and J. Edgar Hoover was the nearest manifest to a papal authority America would ever possess. A case can be made that most bright young men with talent learn to write in college, not earlier, and a Catholic seminary in the early Fifties could not have been the most stimulating, or encouraging place for a writer to find his métier. In conservative times, the private radicalism of the act of writing is more noticeable to a young writer, the sense that he can get in trouble by following his thoughts is quicker to him. A priest, no matter how cultivated his literary education, had to face in a period like the early Fifties the unspoken possibility that his most interesting impulses toward writing could bring him into those no man’s lands of perception which lie near heresy. Nonetheless, and I would be curious to know how he did it, Father Kennedy has become a good writer, a fine and distinguished reporter in the best vein of new journalism — the canon for such quality is a taste for metaphor to flavor one’s facts, and the ability to characterize paradoxes of character in a turn of dialogue — novelistic abilities, in short.

Here is a description, for example, of “the famed sex-researcher, the bow-tied Dr. William Masters who, when he finally broke through the knot of people at the entrance, looked like a prohibition agent about to lead a raid.” A little later, “he sat poker-faced and quiet, lights glinting off his balding head . . . his mouth was a thin line drawn down at the corners, the kind of mouth scrawled on stick figures to depict unhappiness.”

It is a style agreeably achieved, flexible for subject, as poetic as its need. Here for contrast are a few sentences toward the end of his fine piece on Cesar Chavez: “The late midwinter afternoon has drawn on as Chavez speaks of his feeling for the dignity of farm work. Out of one side of the car the golden sun, with the special fire it has in the bitter cold weather, hangs for a last few moments just above the black farmlands to the west. On the other side of the car a full moon is just rising in the deeper blue of the evening sky. ‘My father used to say,’ Chavez notes, ‘that you had to catch the moon right before you planted the fields.’ ”

Yes, there is variety in this collection, and telling portraits which give a clue to the inner life of Catholics so different as Mayor Daley of Chicago, Jimmy Breslin, Father Philip Berrigan, and Pope Paul. There is a psychologists’ convention with some unforgettable moments of humor — one does not know whether it rests in the attenuated use of psychojargon or in the wry misery of the practitioners who seem to give off a distant sense of knowing that, like other totalitarians before them, they murder the English language. The one-liners fly by. A young psychologist reporting on a pornographic study says, “Although this is the last of the hard data, this is not intended to the climax of the program.’’ A study of the Watergate penetrates through the stumbling of the language and the lugubrious pauses to come back with a reasonable scenario of what the motive of such men as Nixon, Haldeman and Ehrlichman might have been before each faltering, or ambiguous or garbled speech. It is, yes, a book of tidbits and fascinating portraits, a photographic view of ecclesiastic trials and right-wing Catholic forums, of Playboy panels on sex and convocations of bishops that give us insight into hierarchical maneuver; it is in short a book which many liberals would do well to read, for the stance may prove fascinating to them, that is, familiar and strange at the same time. Father Kennedy is a liberal, and also most obviously a Catholic — it is a point of view which can seem almost identical to modem liberalism at one point and a space apart the next, for the center of his preoccupation rests, one comes to recognize, in that place where existentialism and Catholicism come near, that sense of how at each moment of existence, in the moral rise and fall of every clean and dirty breath we take, we are growing into more or deteriorating into less. It is the quality which sets these portraits of people and trials, these studies of partisans in committees and councils apart from other works of new journalism where the stance is more savage. New journalism came into existence because of an insight in many young writers (who had found nothing better to believe in than good literary style) that the mysterious and hidden centers of power in the United States were corrupt, and all major figures of left and right were bound to be surrealistic or bizarre. It produced a body of literature cold, brilliant, penetrating, and somewhat empty. A void of philosophical content chills the brilliance and leaches out the ending of most such writing.

It is the virtue of this book that we have a writer who has learned his craft against the grain of his profession, learned to write out of what must have been a continuing inner debate with his discipline and his orthodoxy. The result is a happy freedom, even lightness of style which came perhaps from having shifted heavy objects of dogma in his soul. The quiet prize for us is that we can look again at men and ideas already familiar to us, precisely like Mayor Daley, Pope Paul, my friend Breslin, Cesar Chavez and the Berrigans and see them with the new eyes of a man who is quietly trying to comprehend the ways in which their souls are growing into more, or as in the sad case of some Watergate gents, paltering into less.