Introduction to Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture

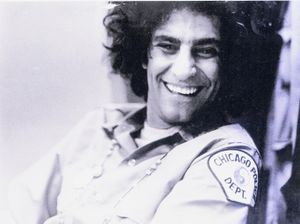

Abbie is one of the smartest — let us say, one of the quickest — people I’ve ever met, and he’s probably one of the bravest. In the land from which he originates, Worcester, Mass., they call it moxie. He has tons of moxie. He is also one of the funniest people I ever met. He is also one of the most appealing if you ask for little order in personality. Abbie has a charisma that must have come out of an immaculate conception between Fidel Castro and Groucho Marx. They went into his soul and he came out looking (or at least he used to look) like an ethnic milkshake — Jewish revolutionary, Puerto Rican lord, Italian street kid, Black Panther with the old Afro haircut, even a glint of Irish gunman in the mad, green eyes. I remember yellow-green, like Joe Namath’s gypsy green eyes. Abbie was one of the most incredible-looking people I ever met. In fact, he wasn’t Twentieth century, but Nineteenth. Might just as well have emerged out of Oliver Twist. You could say he used to look like a chimney sweep. In fact, I don’t know what chimney sweeps looked like, but I always imagined them as having a manic integrity that glared out of their eyes through all the soot and darked-up skin. It was the knowledge that they were doing an essential job that no one else would do. Without them, everybody in the house would slowly, over the years, suffocate from the smoke.

If Abbie is a reincarnation — and after you read this book you will ask: how could he not be? — then chimney sweep is one of his past lives. It stands out in his karma. It helps to account for why he is a crazy maniac of a revolutionary, and why, therefore, we can say that this book is a document, is, indeed, the autobiography of a bona fide American revolutionary. In fact, as I went through it, large parts of the sixties lit up like areas of a stage grand enough to hold an opera company. Of course, we all think we know the sixties. To people of my generation, and the generation after us, the sixties is a private decade, a good relative of a decade, the one we believe we know the way we believe we know Humphrey Bogart. I always feel as if I can speak with authority on the sixties, and I never knew anybody my age who didn’t feel the same way (whereas try to find someone who gets a light in their eye when they speak of the seventies). Yet reading this work, I came to decide that my piece of the sixties wasn’t as large as I thought. If we were going to get into comparisons, Abbie lived it, I observed it; Abbie committed his life, I merely loved the sixties because they gave life to my work.

So I enjoyed reading these pages. I learned from them, as a great many readers will. It filled empty spaces in what I thought was solid knowledge. And it left me with more respect for Abbie than I began with. I had tended to think of him as a clown. A tragic clown after the cocaine bust, and something like a ballsy wonder of a clown in the days when he was making raids on the media, but I never gave him whole credit for being serious. Reading this book lets you in on it. I began to think of Dustin Hoffman’s brilliant portrait of Lenny Bruce where, at the end, broken by the courts, we realize that Lenny is enough of a closet believer in the system to throw himself on the fundamental charity of the court — he will try to make the judge believe that under it all, Lenny, too, is a good American, he, too, is doing it for patriotic reasons. So, too, goes the tone of this unique autobiography. Comrades, Abbie is saying, “under my hustle beats a hot Socialist heart. I am really not a nihilist. I am one of you — a believer in progress.”

He is serious. Abbie is serious. His thousand jokes are to conceal how serious he is. It makes us uneasy. The literary merits of his book are circumscribed by a lack of ultimate irony. Under his satire beats a somewhat hysterical heart. It could not be otherwise. Given his life, given his immersion in a profound lack of security, in a set of identity crises that would splat most of us like cantaloupes thrown off a truck, it is prodigious that he is now neither dead or demented. He has to have a monumental will. Yet it is part of the civilized trap of literature that an incredible life is not enough. The survivor must rise to heights of irony as well. This is not Abbie’s forte. His heart beats too fiercely. He cares too much. He still loves himself too much. All the same, we need not quibble. We have here a document of a remarkable man. In an age of contracting horizons, we do well to count our blessings. How odd that by now, Abbie is one of them. Our own holy ghost of the Left. Salud!