Interview with Norman Mailer

This interview was originally published in Provincetown Arts, Volume 14, 1999: 24–32. Re-printed with the permission of Provincetown Arts magazine and Christopher Busa. |

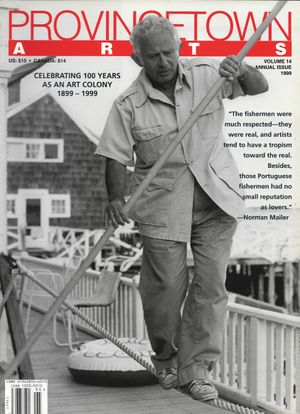

Fourteen years ago, Norman Mailer appeared on the cover of Provincetown Arts. If most cells in the human body change completely every seven years, then Mailer has changed twice since we last looked deeply into his face. Mailer appears now as the author of books unwritten in 1987 — Harlot’s Ghost, Oswald’s Tale, Portrait of Picasso as a Young Man, The Gospel According to the Son, and The Time of Our Time, an anthology of the author’s writings that proves he is his own best editor. Awesome in their range, depth, and ambition, these books may be the finest of an extraordinary career. The author of The Naked and the Dead — Mailer’s first novel, begun in North Truro in 1946 — became a major writer at the age of 26. Now, on the high seas of his 70s, he looks back and calls the widely acclaimed book “the work of an amateur.”

Mailer and his wife, Norris, a painter and novelist whose first book will soon be published, have lived year round in Provincetown in recent years. Mailer writes at a desk under the apex of his brick house on the waterfront in the East End. A picture window looks west along the shoreline to the wharf and Monument, and when the late afternoon sun is bright, he is obliged to cover the view with a curtain. On one side of his desk, a ping-pong table supports stacks of research materials. On the other is a simple mattress on the floor, where the author rests his eyes while working. One senses from the arrangement that the author is the ego who manages the sleep/work cycle between the researcher and the dreamer.

Six of Mailer’s 30 books have been written entirely in Provincetown and 18 others in part. During a bullfight, the bull finds a spot on the edge of the arena where he goes to restore his energy before charging again at the matador. Provincetown offers this sanctuary to Mailer has he does battle with the world. At a cocktail party years ago, Mailer’s good friend, the writer Eddie Bonetti, said, “You know, Norman, I like you in spite of your celebrity.” And Mailer responded, “Eddie, how would you like it if I said I liked you in spite of your obscurity?”

NORMAN MAILER: Anytime I say something that’s not clear, please interrupt. If you think you have a better idea than I have, interrupt — although, caution there! And if you have something that’s not necessarily going to be agreeable for me to hear, that’s fine. I react better to criticism than to compliments.

CHRISTOPHER BUSA: You prefer tension, I know, so I’ve learned never to say anything nice to you.

NM: If you keep telling me how good I am, frankly, I get bored. It doesn’t do anything for me now. When I was young, it did a lot!

CB: So, let’s get a picture of you of your origins in P’town. What possessed you to come here in the first place?

NM: The first visit was in 1942. I had just finished my junior year at Harvard. It’d been a crazy summer. I’d worked in a mental hospital. Then I worked in a small theater group. I think I was here in July. I came here with the young lady who later became my first wife, Beatrice Silverman. We were contemporaries. She was going to Boston University. I was going to Harvard. We decided to go away for a weekend. She picked this place. It had no meaning for me.

CB: What was her attraction to it?

NM: She’d heard it was interesting and fun. Of course, in those days, we were always looking for something that was agreeable to the eye. You know the way kids are. We wanted to see a place that had charm, and was, ideally, perhaps European, because the war was on and there was no question of going to Europe unless you were in the Army. If I recall properly, we took a train from Boston, all the way to P’town, a four-hour trip. It used to end up parallel to Harry Kemp Way, and then came in behind the gas station on Standish Street. At one time, it ran all the way out to the pier, to pick up the fish, but by this time it stopped on Standish. The last part was very slow indeed, from Hyannis on. But then we saw the town — incredible. I’d never seen a town like that.

CB: How long did you stay?

NM: About three days.

CB: Do you remember where?

NM: Yeah, we stayed in one of the rooming houses on Standish Street. We found a room not even one block from the railroad station. There was something easy about it. Naturally, as kids, we were worried whether we would be taken for husband and wife, but it was obvious the landlady couldn’t have cared less. That was the first time I’d ever run into that, because things were pretty starchy in those days. They didn’t look lightly on young men and young women who weren’t married who passed themselves off as married.

CB: Even in Provincetown in that period?

NM: Provincetown has always been ahead of the rest of the nation. One of the things I love about this town and which I always tell people who haven’t been here, is that this is the freest town in America. People can argue. But it’s free now, with the gay population, and it was free long ago when the artists came here. One of the reasons they came was they loved the freedom of the life here. You could live with whomever you wanted and in any combination you wanted. To have sexual freedom has always been terribly important to artists.

CB: What I noticed, growing up here, is the way families and their kids are integrated into that freedom. You went to these wonderful parties and there would be young children there!

NM: I think there just wasn’t money for a babysitter. Or, the best friend, the babysitter, was going to the party also.

CB: You’re cynical, Norman.

NM: No, it’s just that I was at a lot of parties where there were no kids. Particularly, in a period we’ll get to, you wouldn’t have wanted kids there. Some of those parties got pretty wild. Not wild by draconian standards, but a lot of people were getting drunk, people were barfing, occasionally there’d be a fight. You didn’t want a kid running around scared stiff by a fight. Usually a girl with long hair and a certain kind of look in her eyes, slightly spacey, holding a kid on each hand, would come wandering into the party. She wouldn’t necessarily get a great welcome. People wouldn’t be rude to her, but she wasn’t what we were looking for. So, to return to the beginning, we had three days here. The town was incredible. Of course, there were no lights allowed at night.

CB: Because of the war.

NM: There was a blackout, and the streets had a mystery, an 18th-century quality. Occasionally you might see a candle behind a window shade. It gave you a feeling you were back a hundred years or more. Certainly the architecture didn’t destroy that impression. The town looked, surprisingly, a good deal of the way it does now — because of the sand, and because nobody in this town could ever allow any major corporation to come in and sink their roots, thank God!

CB: And that’s what you love about our local democracy — its grass roots, which grow in sand, give an organic texture to the community?

NM: Well, it keeps the community from getting too big. I don’t know that the reason we don’t have high-rises is because the sand won’t take it or because nobody here could agree long enough to allow a corporation to get together enough land to build a high-rise. Thank God we don’t have corporate shithouses that are five, six, seven stories tall, the sort of things that are beginning to deface Hyannis. We don’t have dead-ass, mall architecture all over the place. In that sense, the town is still very much the way it was then.

CB: The eaves of one roof are tucked under the wings of a neighbor’s house. There is a busy urban proximity we share because of the closeness of the houses, yet you get this freaky isolation you mentioned, walking down the street on those foggy evenings where a candle in a window is the only light. It’s like a movie set, but without the overlit intensity of Hollywood.

NM: I wouldn’t disagree — it has that. A friend of mine came up recently. What he was taken with — he’d never been here before — was the enormous sound of the wind down Commercial Street, which I had never noticed. He said, “You never noticed it! It’s as if a jet plane is going by.”

CB: It’s not true you never noticed. You talk a lot about the winter wind in Tough Guys.

NM: Yes, but not that sound, the example he gave. Since then I’ve heard it. An extraordinary sound. Like a propeller whose blades are 60 feet long is sucking the air down a huge tunnel. Anyway, to go back to my first impressions we were only here about three days. Then we left. The following winter we got married, in ’44, a year and a half later. All through the war, once I went overseas (Bea served in the Waves so she never went overseas but she was in uniform), we kept writing, back and forth, about what we would do when this war was over. We would go to Provincetown and spend the summer there.

CB: Does it say that in your letters?

NM: Yes. In June of ’46, we took the boat from Boston to here. We rented bikes. I forget what we did with our luggage. I do remember getting on bikes and looking for a place. For some odd, stupid reason (looking back on it maybe it was a lucky reason), we bicycled clear out of town to the East End and went down 6A — I don’t think Route 6 was even in existence then. We ended up at a place called the Crow’s Nest, which is still there. It’s over on the North Truro line. I always thought I was in Provincetown that summer, but in fact I was in North Truro, maybe a half mile from the line. Now the Crow’s Nest is altogether different — it’s one long building with rooms for rent, housekeeping apartments. In those days, it was separate little bungalows.

CB: Right on the beach?

NM: Right on the beach, in two rows. Some bungalows were right on the water; some were one step back. We were one step back. We spent the summer there and would bicycle to Provincetown just about every day for food, bring it back in our bike baskets, and we’d write. We’d write. Sometimes we’d write in the morning, sometimes in the afternoon. I forget how long we’d write. But in the course of a couple of months there I must have written the first 200 pages of The Naked and the Dead. It was either good luck or bad luck. For one thing, we didn’t get much of a feeling for Provincetown that summer. We were out of the town. We didn’t make friends with people in town. The people we saw that summer were people we’d known already who came up to visit. Family would come — it was hard to get food that summer. When Bea’s folks would come they’d bring certain goodies, like rye bread.

CB: Or bagels?

NM: Yes. It was the first summer after the war, and it was very good for work. If we’d lived in town I might have had a totally different existence. I might have lived here and had a great time, cheated on my first wife, fucked up all over the place, never wrote a word.

CB: You were protected from failure by your will to become a writer.

NM: I’ve thought about it often. It was a summer of great fun, with absolute devotion to work.

CB: Well, you were wired because you came back from the war with the notes that would become the novel.

NM: I wanted to write, I really did. It might have worked in town — maybe we wouldn’t have met that many people. Who knows? In any event, that writing got The Naked and the Dead started. A few months later, back in New York, I got a contract based on those first 200 pages. I worked all year. I’m not even sure we came back the following summer for more than a visit or two. My cousin, Charles Rembar, a fine lawyer who has argued literary cases, such as the obscenity trial concerning the U.S. publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, had a house up here. Kurt Vonnegut was definitely living up here, but whether it was that year, 1947, or whether it was later, because I was back here in ’51. I can’t say. But after the summer of ’46, I worked on the book all year and finished it in the fall of ’47. Spent the winter and spring in Paris, came back to New York in the summer of ’48 — I don’t know if we were in Provincetown that summer. Then went to Hollywood for a lot of ’49. I think by ’50 we were back here. Bea and I broke up in ’51. I started living with Adele Morales and we came here and rented a place. One summer we rented the Hawthorne house that’s up on Miller Hill Road. At one time it was the only house on the hill. Now there are about 15 houses or so it seems. That was a wonderful house. It had a little studio as well and that was where I worked on Barbary Shore quite a bit. That book was started in Paris, continued in Vermont, where I spent a winter before I went out to Hollywood. The first draft was finished in Hollywood. Then I worked on it up in P’town in that house, then bought a house in Vermont, then finished it in late ’50. The book came out in May of ‘51.

CB: If we were to jump from the past to the very present — you’ve seen Provincetown change over 50 years. In one sense you’ve said it hasn’t changed that much. Its attitude remains open and tolerant.

NM: Architecturally it hasn’t changed that much. In terms of what the town is like, it’s changed immensely. The people here now are altogether different from the people then.

CB: The town is certainly less bohemian. Now, it is possible to say with plausible irony, most of the gays are straighter than the straights.

NM: In the early days, and this carries through to the ’60s, the town had, essentially, one ongoing tension. That was between the Portuguese and the artists. Some of the Portuguese fishermen were wilder and stronger than any artist you’d ever find. We’d get drunk together and have arm-wrestling contests, often. I remember Bottles was the one guy nobody could ever beat.

CB: Bottles?

NM: Bottles Souza. He was really good at arm-wrestling. He had a reputation for being the strongest man in town, which was saying a lot in Provincetown in those days when you’ve got all those fishermen. I remember asking him once, “Bottles, did you ever know Rocky Marciano?” They were contemporaries. He said, “Yeah, I knew Rocky. I knew Rocky when.” I was fascinated. It came over me, sure, he’s the strongest guy in Provincetown, he’s heard about this strong man in Brockton. They were both about 17 or 18. So maybe one day when they are all drunk they get in a car and drive down to Brockton to look up Rocky Marciano and arm-wrestle. So I said, “You knew him?” “Yeah,” he repeated, “I knew him when.” I said, “Bottles, what was he like?” Bottles looked at me and said, “Rocky? Rocky was crazy!” That’s all he ever said about Marciano.

CB: I never met Bottles. My local hero, a half generation after your time, was someone perhaps less strong but equally charismatic — Victor Alexander, the goated bartender at Rosy’s, who wore a gold stud in one ear before it was fashionable.

NM: The tension in the town then was between the Portuguese, who were Catholic and observant and very family-oriented, prodigiously family-oriented, and the artists, who came every summer with a different mate, sometimes a different kid. Of course, we were smoking pot. It was all right to get drunk in town — but not pot. That was the tension then. Now the artists have virtually disappeared. You’ve still got a good many over at the Fine Arts Work Center, but you don’t have that feeling that this is a painter’s town the way you used to, when you had Motherwell, Hofmann, Kline, Baziotes, Helen Frankenthaler when she was married to Motherwell, and you had a number of younger artists who were building their reputation, damn good people like Jan Müller, Wolf Kahn, and your father Peter Busa. For people who knew the art world, there must have been 20 artists here of note any given summer. Now it’s no longer a vanguard, let’s put it that way.

CB: I’m very conscious of what you say. I couldn’t live in Provincetown, especially in the winter, without a Work Center.

NM: Get it straight, I’m not objecting to the Work Center. I wish there was more of that. In those days there wasn’t a Work Center, which would have been a very good time to have one. But there were all these well-known painters, and that gave a certain tone to the town, plus an interesting tension. The Portuguese looked askance at the artists. They looked at these great painters and didn’t know what they were doing.

CB: There was a cross-cultural communication. For example, my father traded plumbing services for painting lessons. The plumber’s idea of paradise was to paint a nude figure.

NM: Also, there were women who came up here to study art and ended up marrying or living with a good many Portuguese fishermen. There was a lot of that. Those Portuguese fishermen had no small reputation as lovers. There was one grand lady I knew, who shall remain nameless. She was big, she was blonde, and she had been married to a distinguished literary intellectual in Western Massachusetts. He was a renowned critic and she was a fabulously beautiful woman, and big as a frigate. She left him that summer, came here to live, and ended up living with a young fisherman for an entire year. And if you were a young painter or a writer and you were invited out on a fishing boat, that was a big deal. The fishermen were much respected in those days, and properly so — they were real, and artists tend to have a tropism toward the real. Provincetown was not only most agreeable to the eye, but it was real, with real people. It had been a whaling town. It was real enough that when the Pilgrims came here, they decided to move on because it was a little bit too real. It wasn’t nurturing.

CB: It was harsh. Even the Indians only came to Provincetown during the warmer months, like the present-day New Yorkers. They would come down from the mainland, out to the edge, to get shellfish and have a good time. They didn’t live here in the winter. The clay base of glacial Cape Cod ends at High Head in North Truro. The sea spit up all the sand that is Provincetown. So our turf is insubstantial and the foundations of houses are fragile. We are protected by the difficulty of surviving here. It’s very hard to live here, and in fact, in the days you remember in the ’50s and ’60s, hardly anybody lived here in the winter.

NM: A friend of mine, John Elbert, spent a winter here, and I came up to visit him in ’57 or ’58. I’d known him in the Village. He was looking to save money and write. It was a grim winter, nothing was open.

CB: You are obliged to face isolation — that’s the test, a marvelous test. Can you go in a room, face a blank sheet of paper, and come up with something that’s worth the sacrifice?

NM: When one’s a young writer there’s that awful feeling that life is going by and you’re not getting enough experience for your future writing. It’s hard to be a young writer and a monk. It’s why so many young writers will let a couple of years go by before they start another book. It’s only when you get older that you go from one book to another, where you finish a book and two months later you’re on your new book. In the beginning, it’s two or three years between books because you want to fill up; you want to have new experience. The irony, of course, is that the immediate experience you get is not stuff you can write about; in fact you probably shouldn’t touch it yet.

People have always said to me, “Why don’t you do an autobiography?” The main reason is I don’t want to use up my crystals. What I mean is that certain experiences have an inner purity to them. They remind me of a crystal. I use the word advisedly. Your imagination can project through this experience in one direction, and you can have one piece of fiction. What I call a crystal experience is not a simple one, rather a most complex one, but it has this other quality that it can be studied from many angles to produce many results. So, whenever you write about something that’s a crystal experience, you are dynamiting one of your richest narrative sources. I don’t want to write an autobiography because that’ll mean I’m done as a writer.

CB: The autobiography would reveal your crystals — to yourself?

NM: No, it would use them up. The crystals are right in the middle of my life. I’d have to use them if I were to tell a reasonable narrative of my life. I’ve never written directly about any of my life. I’ve never written directly about any of my wives, for example, for just that reason. The experiences were too rich, too complex, and too enigmatic to use directly. As long as I don’t use them directly, I can write about 20, 30, 40, 50 women on the basis of the six women I’ve been married to, plus a few other women, of course.

CB: Thank God for breaks between marriages, because you get some fresh experience. I’ve only been married twice, yet I define myself as a serial monogamist. I go from one woman to the next woman, and I try not to be two-timing the woman I’m with. When you start doing that, the relationship is over. I got trained as a husband and enjoyed the idea of being married to one person, and I also felt that, sexually, we could get better rather than worse, just like Olympic skaters improve their act together. But the thing you said about protecting the crystal is vivid. I can see how you could go through the same form and come out a different side. For example, in your last novel, The Gospel According to the Son, you deal with Christ’s chasity. Your very knowledge of women now provides you with another prismatic direction.

NM: I wouldn’t say that. I had trouble with Christ’s chastity. When you write, there are certain things that you work to get, and there are other elements that come to you as gifts, almost out of the very mood of the writing or the momentum of the work. You have to count on things coming to you or your work is no good. And then there are parts that don’t come to you, and you’re not as good as you thought you’d be, so you work and sweat it out. Christ’s chastity was not a simple matter for me. A lot of people complained about the book. They will point to one novel where He had homosexual affairs, another where He had an affair with Mary Magdalene. What they don’t understand is that I never allowed it to become a temptation. I wanted to do the Christ that presented to us in the Gospels. I was trying to understand that story. I wanted to write that story in a way that I could understand it.

CB: You wanted to write the available story in a comprehensible way?

NM: Yes, I wanted to treat the Gospels as if they were absolute gospel, in other words, received information that could not be departed from. That’s difficulty was interesting. To take Christ in one or another imaginative direction would have been very easy and would have been my natural inclination.

CB: The restraint of staying faithful to the Gospels is the key to its success, I think. There’s tremendous compression. You refer to Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the authors of the synoptic Gospels, as scribes who didn’t get it exactly right, perhaps because they wrote about Christ a half century after His death.

NM: Well, they’re not scribes. Let’s call them Gospel writers, because the scribes to me had a particular meaning — the people, who were in a sense the court reporters, the professional intellectuals in the temple.

CB: One of the things that interested me in your novel was how the authority of the writer was linked to the authority of Jesus. Jesus got His authority by knowing the Scriptures, by knowing the lessons of the Old Testament. He can quote what Moses said. He can quote the prophets and His authority derives from His knowledge of tradition. It is so simple that it is audacious. The opening sentence of the book — “I was the one who came down from Nazareth to be baptized by John in the River Jordan” — is direct and stirring, the voice of a human being. We’re not talking about God, we’re talking about the Son of God as a human being.

NM: That was my intent. What I wanted to do was treat the man in Jesus Christ, not the superman. I found the Gospels almost irritating. Obviously, if you read the Gospels, as in reading Shakespeare, you’re going to get certain sentences that are part of our literary culture. But generally speaking, reading the Gospels is not an altogether agreeable experience. For one thing, they are not that fabulously well written.

CB: I knew you might say something like that.

NM: For another, Jesus is not a man in the Gospels. He’s being told that God sent His Son as a human being among us, but the fact of the matter is that Jesus is a superman. He’s never challenged in a way where you can feel any fear in His heart. I thought, no, no, no. Any man, even if also a god, who goes through those extreme experiences is going to feel a great deal of fear. And that was the way I wanted to treat it.

CB: In your book one thing I find incredible is that Christ Himself never says He is the Son of God. Other people say it about Him. He questions whether He is really the Son of God, so the final authority is always beyond Him.

NM: At least in my book, there is some doubt in His mind, not whether He is the Son of God, but He doesn’t know how close God is to Him. People tend to think, well, you’re the Son of God, so it’s automatic.

The key thing, which is true for all profound religious experiences — not that I’ve necessarily had that — is that even if you’re endowed with or are the representative of what everybody in places like AA calls a “higher power,” this power is not always with you. It’s often, signally, not there. When people have faith, they often go through excruciating experiences when they feel the absence of faith.

CB: Christ’s mood comes out when His faith wavers. The variety of religious experience corresponds to the variety of human moods that are mixed in any single character. A character is not just, say, a sourpuss, but may inspire a thousand different adjectives, equally accurate. It’s like the ups and downs of being in love.

NM: Very good, it’s very much like being in love. There are times when there is no doubt in your mind that you are in love, and there are times when you assume the love has been withdrawn. Where is it, what happened to it? In that sense, I wanted to treat Christ the way I would treat, if you will, a saint. The first thing about saints is that they don’t know all the time that they are saints.

CB: Your description of Capernaum, a town in ancient Palestine on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee, reminds me of Provincetown, where the mouths of men are also painted red. Simon Peter tells Jesus how Capernaum, “though only a small city, was favored by men who did not know women but other men. So I learned that such men would cover their lips with the juice of red berries, and in the taverns they would speak of how the bravest of the Greeks were Spartans, who were great warriors but lived only to sleep in each other’s arms.” Jesus’ disciples dispute this, and Peter says: “Spartans also live with the sword. Whereas these men of Capernaum live with the coloring that women chose for their lips.” I can’t help but feel there is a little bit of Provincetown in Capernaum.

NM: How can I pretend I didn’t think of Provincetown once while writing that passage? But Capernaum was known for that.

CB: I love the vivid lipstick made from “juice of red berries.” You said once that talking about religion, for you, was more embarrassing than talking about sex. Another episode I love is when the disciples come to Christ, depressed about their failures to cast out demons. They lack His skill. It is a skill that exhausts Jesus. He can’t cast out too many demons. There is a limit to His power. His disciples are sometimes effective, but more often they are not as good as He is in casting out demons, predicting the future, or curing lepers.

NM: That goes directly to my notion of a divine economy.

CB: Economy?

NM: Economy. In other words, in Tough Guys one of the happiest moments I had — I didn’t write the book here but I edited it here — was when the father, Dougy Madden, was talking to the son about pro football and handicappers. The father says, “Listen, if God handicapped the football spread, He’d be right 80 percent of the time.” The son asks how he arrived at that. The father says, “Well, the best handicappers, for a little while, can be up to 75 percent for a few weeks, not more. So I figure if they do 75 percent, God can be 80 percent, no trouble at all.” Madden’s son asks why God can’t do 99 percent or 100 percent. He just passes over the teams at night and He sees what their energy is and He says the Giants are up and the Steelers are down. I’m going to pick the Giants. And He’s right 80 percent of the time.” So Madden’s son says, “Yeah, but why can’t He do it 100 percent of the time?” And the father looks at him sternly and says, “Because footballs take funny bounces.”

CB: Oh, God that is funny!

NM: The the father says to the son, “If God had to work it out, it would take 50 times more effort on His part, and it isn’t worth it.” So, you see, my feeling has always been that the divine economy is very much with us all the time, but not totally, not totally, because the gods must focus and do not have complete powers. They have what they have, and it can be immense, but they don’t have more than that. I employ that principle all through The Gospel According to the Son, which is that God has other things to do besides taking care of His Son down here.

CB: So the ethical is limited by a need to balance sacred energy on the fulcrum of divine purpose? My belief is that God didn’t create us, we created Him, but that may sound like blasphemy to you.

NM: Well, that is beyond my purchase, and I don’t want to get into it. What I will say is that if we take the notion that God is capable of doing everything and anything at any given moment, it takes away the last of our human dignity. I much perfer the notion that God is just doing the best that He or She can do, or that it’s a marriage that They can do. I’ve never believed, for one moment, that God intervenes at every moment and takes care of everything. So my god is an existential god, a god that does the best that can be done under the circumstances. A tired general will not always prevail. I wanted to get across the Gospel that when Jesus removed demons from people, He didn’t do it for nothing. It cost Him a great deal. He was as exhausted as a magician after a long night of performance.

CB: Speaking of performance, the 1996 cover subject of Provincetown Arts, Karen Finley, told me she decided to become a performance artist when, as a teenager, she witnessed speeches at the Democratic convention in Chicago in 1968, when people like Abbie Hoffman and Allen Ginsberg were giving these emotional rallies before larger audiences. She saw them as an art form. The whole concept of performance art started in this political realm. In other words, there was a perception about politics as theater. In your book, Of A Fire on the Moon, about the Apollo moon shot, you have a concluding section called “A Burial by the Sea” A broken-down car is buried in a P’town backyard.

NM: Half-buried.

CB: Half-buried. It’s almost like a religious cermony. Heaten Vorse quoted from the Song of Solomon. Somebody else read from Numbers.

NM: Eddie Bonetti read from a poem he’d written about this car that had been poorly conceived: “Duarte Motors giveth, and terminal craftsmanship taketh away.” You’re right, but I wouldn’t call it a religious cermony, it was a quasi-religious ceremony. It was more moving and more sacramental, in an odd way, than anyone expected. Everything about it was bizarre. My friends, the Bankos, had this hole dug by a bulldozer, and the bulldozer pushed in the car. It sank halfway, and the half that stood up looked so much like a bug coming out of the earth that Jack Kearney welded on antennae, pieces of metal that became antennae. Really it looked like the biggest beetle you’ve ever seen.

CB: A ghastly beast — I saw it at the time. I went earlier today to look at the site.

NM: They took it away.

CB: It looked like there was a mound of earth and they put some vegetation over it.

NM: May they decided it was cheaper to cover it with dirt and grow something.

CB: One of these days I’m going to go over there with a shovel and see if it’s still there, but I worry about disturbing the bones of the dead. I did think the section in your book is interesting for the ceremony and the invocation of religious language at a time when, as you say, marriages were breaking up. Five marriages that you witnessed that summer.

NM: And one of them was mine.

CB: You connected this with the moon shot, as if our lunar assault was destroying our ability to sustain love.

NM: I was married at the time to Beverly Bentley, and I’ve never known a human being who was as sensitive to the moon as Beverly. Whenever there was a full moon, I dreaded it, because about two in the morning she couldn’t sleep and she’d go out on our deck — at that time we were living at 565 Commercial Street — and she’d bellow at the moon. She’s say, “Oh, Moon! Don’t you pretend that I am not looking at you! I am looking at you. Moon, so you can speak to me!” She’d go on and on with that, not out of her mind, just very enjoyably half out of her mind, and loving it and half believing it. She always had a prodigious imagination. If a small cloud passed in front of the full moon, that to her was a sign. Our marriage broke up that summer. And I felt; let’s not say the moon had nothing to do with it.

We had landed on the moon, after all, which I felt was a great violation because it was done without ceremony, down at NASA, where they could have apologized for landing on the moon. Primitives used to do that. If they cut down a giant tree, they were all too aware that tree had a spirit, which I suspect is true. I think all great, noble trees do have spirits. I think little trees have spirits too, but it’s the old story of divine economy — their spirits can’t get too much together. But a giant tree can mean something. So when a tribe cut down a giant tree, a religious ceremony was invoked. Of course, NASA never did that. There was never one moment when the people at NASA said, “We recognize that the moon has been a source of endless stimulation to generations of poets, and is deep in the culture of the West, not to mention other cultures, and so we are very proud of landing on the moon, but we also apologize to those powers in the universe about whom we know nothing if they have been disturbed.” Can you imagine the poor bureaucrat who wrote that speech and delivered it? He wouldn’t have been long at NASA. There was something so cold, so steely, so mechanical about NASA. That is one of the reasons it never captured the public imagination. Think about what a feat that was. Yet there was no spirit, no sense of awe about invading our symbol of madness, mystery, gestation, and recurrence.

CB: The lawyers have a term, “excited utterance,” to describe statements said under the compulsion of an emotional moment. The astronauts had no quotable excited utterances — no surprise of the heart.

NM: Nothing but “a small step for man and a mighty step for mankind.” It’s not that good a quote, nothing remarkable. It doesn’t reach. But a requirement of NASA was to be deadly dull. These astronauts, however, had a double life. They all had Corvettes in those days and they would drive at 100 miles an hour down those Texas highways, one foot away from each other. When they cut up, they cut up. I’m not talking about Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins, who were on Apollo 11, because they were probably the purest of the pure, looking back on it. They took the three most dependable guys for that shot. Let’s say they took the six or nine guys out of the pool of 25, or whatever they had, and said, “Among these nine are the guys we can count on.” And when they had those three, they said, “This is a very good threee. Let’s go with them.”

CB: To be conscious of the excitement would have been a distraction from working.

NM: The work was prodigious. The amount of detailed work tended to keep them from getting excited. Also, the whole idea was not to be excited. If you get excited, the awe of the experience is going to weigh on you, and we don’t want that. In order not to feel fear, you’ve got to explore every realm of the unknown technologically, which they did. They were made completely familiar about every aspect of the job, but ultimately some essence was completely unfamiliar.

CB: I want to make a connection between the moon and the spirituality in a work of art. I grew up, with an artist for a father, valuing art as a vessel for spirituality. Of the painters you’ve known in Provincetown, can you say anything about discussions you had with them? For many years, Robert Motherwell was a close neighbor. I remember seeing you at the National Arts Club in New York when Motherwell gave a speech following the award of a medal. You were in the front row listening to every difficult syllable he uttered.

NM: Motherwell was an immensely intelligent and cultured man. But we never had a serious discussion. We weren’t that close, and there was a kind of tradition among those painters never to talk about art. If some of the artists got drunk, they occasionally may have had a private argument about art between two of them. There were forums at the Art Association but I don’t remember anything remarkable being said. What mattered was the presence of the artists.

Maybe one reason I never got into a discussion about modern art with them is that I always felt such conversations never went anywhere. How far can words carry an artist? To this day, I find most writing about art to be poetic explorations that depart very quickly from the experience of looking at a painting. The writer goes off on some inner collaboration with his or her own experience. The painting becomes like a distant object from which one is receding at a great rate in one’s vehicle of metaphor. I find that terribly tiresome. On the other hand, technical writing about art — the nature of the pigments used, and the method of their application — while useful, is not going to stop anyone’s traffic. Perhaps there are more painters worth writing about then there are writers worth writing about — that’s a large remark, but it comes out of my general impression.

Maybe there are a thousand painters in America you could take seriously, but I don’t know if there are a thousand such writers here, I don’t know. But I do think that when you write about painting without involving yourself with the life of the painter, I’m not sure the criticism has the same value as it may when you are reviewing a book or doing a piece of literary criticism. If you have 10 people reading a book, and you have 10 people looking at a given painting, an important painting, Painting does not lend itself to critical language. Rather it’s a springboard to all sorts of sensations, emotions, metaphors, indulgences, new concepts — whatever — but it’s as if each of these people is exploded out from the work. That is the excitement of painting. You go to see a painting to be shifted, startled, moved into new awareness. Whereas, very often with a work of literature what you are looking for is more resonance than one’s own thought. To a degree that we learn about the life of someone else, which you get out of a good book, we understand the life we would otherwise never have come near to. So we are larger, more resonant within.

CB: When you were doing your interpretive biography of Picasso you must have thought hard about the issue you just articulated — the limits of what you can say, verbally, about a visual experience. When did it occur to you that you had the ability to do that book, especially your ability to substantiate your assertions in actual descriptions of Picasso paintings? That, to me, was the accomplishment: locating your insights in the work itself.

NM: Thirty years before I started that book I signed a contract to do a book on Picasso. It never went anywhere. I ended up writing a 200-page philosophical dialogue that was published in Cannibals and Christians. Looking at reproductions of Picasso’s work for two months at the Museum of Modern Art stimulated that writing. But I wasn’t ready to write about Picasso. I didn’t know enough about him. I really didn’t know his life. He stimulated, sent me on a long, wonderful voyage, and I honored him for it. But I wasn’t ready to write about him. Over those 30 years many good books and bad books were written about him. By now I had developed a sense of the honor and the shoddy in another writer’s style. You get a very good sense of the part of the writing that has integrity and the part that is meretricious. This is true for all writers, even the very best.

I’ll show you in Shakespeare a hell of a lot of meretricious writing. Parenthetically, what Shakespeare loved was having wonderful lines of dialogue, back and forth, and wonderful monologues. So he’d bring people together to produce this language. It had nothing to do with reality — which may be one of the reasons Tolstoy hated Shakespeare so much. Shakespeare was not interested in reality or morality, as an intimate matter. He was only interested in morality for its relation to language.

To come back to what I was saying, you can find the meretricious in a writer no matter how great they are. You cand find it in Proust where he is needlessly long at a given moment, until finally his virtues become his vice because he’s so good at it. Certainly, when you are reading an average good writer, what’s fascinating is where they are telling the truth, as you see it, and where they are not, where they are fudging it. If you’ve been a writer all your life you do have quite an authority there. You are not unlike some high ecclesiastic who decides that the evidence here is such that we will or will not call this woman a saint. There are standards, intimations, instincts you’ve developed that give you a wonderful sense of when someone is having a sincere religious experience and when they are having a false one. With writers, if you know how to read them, and it may take being a writer for 50 years, then you see through the writing to where they know a lot of where they don’t. And that inspires your own writing, illumines it.

One reason I was able to write the biography of Picasso 30 years later is because of all the books written in between that I could read and study and get a great deal out of. Not only good books, but ones where I could say I think I understand Picasso better than they do. Of course there is a tremendous amount of bad writing about Picasso by some of the most established writers about him — they love being academics about his work, and that’s not the way to go to Picasso.

CB: You make clear that for Picasso, creation itself is a violent act. When you speak about dullness in the imagination of NASA, sometimes I think your idea of a good party is to invite the enemies of your friends.

NM: No, only certain enemies.

CB: I’m teasing.

NM: Norris, my wife, thinks my idea of a good party is when I do all the talking.

CB: You’ve found a woman equal to you in terms of her centeredness. Even though you’ve been married six times, you’ve now been married to Norris longer than most people have been married at all.

NM: We’ve been married 20 years and have been together about 25 years.

CB: And when did you learn she was born on January 31st, the same day as you?

NM: First night.

CB: That must have been a shocker.

NM: It was curious. We looked so unalike and were so different that it was interesting to have something in common. But it wouldn’t have mattered what her birthday was. Over time I’ve learned that we not only have the same virtues, but the same faults.

CB: Do you remember a woman named Cinnamon Brown? Rumors say you know of her.

NM: Yeah, sure. That look of panic you just saw in my eyes was me asking myself if there were two Cinnamon Browns.

CB: You cast Norris in this role of Cinnamon Brown, at a small party in New York, dressed in a blonde wig and brazen makeup, and introduced her as a girl from the South who’d come north to enter the skin-flick business.

NM: The real art was that we did it with two extremely sophisticated people, Harold and Mara Conrad. Mara was one of the smartest, hippest women I’ve ever known. The idea was precisely to fool her. As I remember, Harold was in on it, or I don’t think we could have pulled it off.

CB: I once pulled a fast one like that, taking a woman, Mary Boyle, to an all-men’s club in Provincetown, the Beachcombers, for a Saturday night dinner. Women are not allowed; so Mary put a theatrical corset around her chest, removed her false teeth, and put her hair under a beret. I introduced Mary at the Beachcombers as a guy I’d picked up hitchhiking in Bourne. His name, I said, was Marty Anus, a French name pronounced “a-NEW” and spelled Anous, but vulgar Americans always mispronounced it. All these guys bought it.

NM: No doubt they were drunk — the real test at the Beachcombers is the ability to hold your booze.

CB: I know you could match them.

NM: Well, I got there a little too late, too old. I realized that to enjoy this I had to be able to drink on Saturday night the way I used to in the old days. I can’t do that anymore.

CB: So much of your knowledge of the body comes from an interest in sports, especially the dynamic balance of a performing athlete. Your characters, both within themselves and with others, are moving through complicated turns, where they are at once off balance and in balance, yet the center of gravity is maintained in evolving alignments.

NM: The turn for me came in the ’60s. In the first half of the ’60s I was doing my best to give up smoking, and my style changed, starting with An American Dream. I smoked two packs a day for years and was addicted for 20 years when I started to give it up at the age of 33, in 1956. It took me the next 10 years to give it up totally. It was very hard to write when I was giving up cigarettes. Smoking enables you to cerebrate at a high, almost feverish rate. Your brain is faster when you smoke cigarettes, which is why working intellectuals, particularly, do hate giving up their addiction. I discovered, yes, I had much more trouble finding the word I wanted, but the rhythms were now better. Before I had been writing more like a computer, if you will, imparting direct information, stating things. Gradually I learned a more roundabout way of discovering the meaning of a sentence, rather than knowing it before I started. Also I began to write in longhand, rather than with a typewriter, Writing became more of a physical act, with more flow to it, but with less celebration in each sentence. I attribute the development of a second style to giving up smoking.

CB: Out of necessity. It took you a full decade to get comfortable writing without smoking?

NM: I suffered greatly for years, which gave something to the new style, because when you’re suffering, to get the writing out when your behind is not entirely clear, you truly have to work on clarity.

CB: Much of the new clarity didn’t exist before. I was just reading what James Baldwin said about “The White Negro,” which you published in Advertisements for Myself. He felt he couldn’t understand what you were talking about.

NM: He may not have agreed, but I think he understood. He was saying, “How dare you write about black experience?” That irritated the hell out of me. I said, “Jimmy, how dare you write about white experience?” In Giovanni’s Room he had written about two white boys. My whole feeling was, of course, we can cross over. Is a man never to write about a woman? Is a woman never to write about a man?

CB: The right to write about another’s consciousness is what’s at stake.

NM: If we can’t do it, we may be doomed as a species. That is a large remark. But unless we are truly able to comprehend cultures that are initially alien to us, I don’t know if we are going to make it. This applies to all sorts of things. If we can’t begin to imagine the anxiety and pain and disorder that is caused in all parts of the cosmos by birds dying in the oil of the Exxon disaster, or if only a third of us can recognize that, then worse things will happen. What terrifies me about human nature is our stupidity at the highest levels. For example, all the Y2K crap going on now — what was going on in those guys’ heads that they couldn’t look 50 years ahead? And now we are going to go into cloning, fooling with the gene stream? If we can make an error like Y2K and not be able to see in advance what the mistake will do, in the very system these guys developed and invented, then I am terrified. As an extension, the idea that you can’t write about things you haven’t immmediately experienced is odious to me. There is much too much journalism in our lives now. I remember when I did the biography of Marilyn Monroe; the first question everyone asked me was “Did you know her?” I’d say no. Immediately the shades would come down on interview shows. In effect, if you didn’t know her, what you wrote about her was not worth reading.

CB: There you said what I was trying to hear.

NM: I believe it. You need an awful amount of luck to be a novelist, and I have had a lot in my life. I didn’t have to spend half of my 50 years of writing earning a living at things I didn’t want to do, which is killing to talent. This ability to reinvent cultures, to make imaginative works of them that are more real than any pieces of journalism, is crucial to our continuation. For many years I felt we were just scribblers and it didn’t mean a damn thing. What I was recognizing was that what we write doesn’t change anything. Everything I detest has gotten stronger in the last 30 or 40 years; plastic, airplane interiors, modern architecture, and suburban sprawl. One of the things I like about Provincetown is that it hasn’t changed that much, it hasn’t been poisoned the way cities like Hyannis have been ruined. I’ve come around to feeling that what we do as writers is essential and important. Consciousness is enlarged gently and deliciately, yet powerfully, and it takes great literature, like great music, painting, and dance, to make that happen. I’ve come to believe that the function of the novelist is more important now than ever, precisely because the serious novel is in danger of becoming extinct.

CB: If we connect these remarks to your novel about Jesus we see that the source of His wisdom resides in the parabolic language that He uses even more skillfully than the Devil.

NM: One of the reasons I don’t altogether enjoy talking about that book is that it is not altogether my book. Some of the best lines in the book come from the Gospels. When you write a book, you want to be able to take credit for it. The Gospel According to the Son — only half-credit. The Exeuctioner’s Song, which a lot of people think is my best book, I also can’t take whole credit for. I didn’t write that incredible plot. God or the forces of human history put that story together.

CB: Shakespeare took almost all of his plots from secondhand sources, such as Holinshed’s Chronicles. He absorbed history and earlier versions of his plays as cultural documents, then fully re-imagined them.

NM: You either write your own story or you don’t. The story, in novel writing, is a powerful element. There are very few great stories and I would like to think that I came up with a great story once or twice. But I don’t know I have, except when I have borrowed them, such as Gospel or Gary Gilmore’s story.

CB: Borrowed stories are embedded in the culture’s legends. Newborn babies are not original, yet each generation values them nonetheless.

NM: It’s one thing to take legends and bring them to life, to the best of your ability — it’s a high activity and I’m very happy to have done a little of it. But I go back to what I’m saying: my real excitement is when I do it myself, when I’m not dealing with a legend, when I make up the story, as I did in Ancient Evenings and Harlot’s Ghost or The Deer Park and An American Dream. Those novels give me more pleasure, when I think about them, than when I think about The Gospel According to the Son, where the difficult thing was to bring a legend to life.

CB: With Ancient Evenings you’re dealing with an Egyptian culture more than a thousand years before Christ. We had lunch at Napi’s a few weeks ago and you were telling me about the research you did for that book at the annex to the New York Public Library, leafing through a huge book depicting the Battle of Kadesh, the first battle recorded in history, recorded in drawings.

NM: That book is called the Lepsius Denkenmahler. It was published in Leipzig about 1838, soon after the first major discoveries in Egypt, and the Germans were absolutely wild on the subject. Ancient roots! It gave one a great sense of how they used to print books 150 years ago, as opposed to how they do it now. Boy, they printed books in those days. The pages were approximately 30 inches long and maybe 15 inches high, and when you opened it — heavy, stiff buckram covers — and turned a page, it was like coming about in an old catboat in a light wind. The thick canvas mainsail lopes over.

CB: Here we have a picture of you doing research and enjoying the research.

NM: Not all research is that enjoyable. In the Lepsius Denkenmahler you go through maybe 100 pages of tomb drawings on all the details of the battle of Kadesh. You’ll see donkeys screwing each other, men fighting, a horse nosing out a soldier’s food he shouldn’t be eating in an encampment.

CB: To count the dead, the hands of the fallen are cut off and massed in a big pile, and a lion eats these hands, crunching the bones, and gets so sick he dies. Is that depicted in the drawings?

NM: I forget where that detail came from. I don’t think I made it up, but I might have. I don’t know. The research all goes into the book, and I don’t want to take it along with me when I’m finished. I want to empty my mind for the next piece of research.

CB: On your desk here are stacked the works of Goethe, along with a big German dictionary. You are presently learning German to read Faust in the original. You are an old dog who learns new tricks. Learning for you is connected with imaginative expansion.

NM: The mind is like a muscle. If you exercise your brain, it stays more in working order, as you get older, than if you don’t exercise it. I once wrote: “There was that law of life, so cruel and so just, that one must grow or else pay more for remaining the same.” That’s near the end of The Deer Park. Generally, when you write a good line, it is for others to lead their lives by, because you’ve already discovered the meaning. This line is something I live by. Whenever I’m getting lazy, this is the line I whip myself with. “Stay lazy, buddy.” I tell myself, “and you’ll be gone pretty quick.”