Mailer and Me

Barry H. Leeds

Originally appeared in Drunken Boat 6 (Spring 2004). Cross-posted here with permission from the editor and Barry H. Leeds. See 96.4. |

When I was a sixteen-year-old Ordinary Seaman on the S.S. John M. Bozeman, a shipmate recommended The Naked and the Dead. My father, particularly impressed by “The Time of Her Time,” gave me Advertisements for Myself. I still have that beat-up copy, a much-underlined and annotated first edition.

I was living on Charles Street off Greenwich Avenue in the Village, a year out of Columbia, when I read The Deer Park and the first version of An American Dream, serialized in Esquire’s first eight issues of 1964. During the 1963–64 academic year, I was 22 years old and holding down what amounted to four jobs: revising and wrapping up my M.A. thesis at Columbia on The Private Memoirs of Sir Kenelm Digby; teaching two evening English composition courses at CCNY; taking a 12 hour course load toward the Ph.D. at NYU; and working nights at the New York Times credit desk, making decisions on whether to let “business opportunity” ads run without prepayment and taking my break at Gough’s, the great, grubby newspaperman’s bar across the street, where a draft beer was still 15 cents and you could get a big hamburger with fried onions and french fries for 85 cents. During this time, I wrote my first letter to Mailer. Given the arrogant tone of it, coupled with my knowledge now of what his life was like at age 40, I’m not surprised he never answered. Today, I can be more understanding of his reticence. He tells us much about his perspective at the time in the introduction he wrote eight years later for the 1971 edition of Deaths for the Ladies (and other disasters):

| “ | Deaths for the Ladies was written through a period of fifteen months, a time when my life was going through many changes including a short stretch in jail, the abrupt dissolution of one marriage, and the beginning of another. It was also a period in which I wrote very little, and so these poems and short turns of prose were my lonely connection to the one act which gave a sense of self-importance. I was drinking heavily in that period, not explosively as I had at times in the past, but steadily — most nights I went to bed with all the vats loaded, and for the first time, my hangovers in the morning were steeped in dread. Before, I had never felt weak without a drink — now I did. I felt heavy, hard on the first steps of middle age, and in need of a drink. so it occurred to me it was finally not altogether impossible that I become an alcoholic. And I hated the thought of that. My pride and my idea of myself were subject to slaughter in such a vice.

. . . I used to wake up in those days. . . , and the beasts who were ready to root in my entrails were prowling outside. To a man living on his edge, New York is a jungle . . . It was not so very funny. In the absence of a greater faith, a professional keeps himself in shape by remaining true to his professionalism. Amateurs write when they are drunk. For a serious writer to do that is equivalent to a professional football player throwing imaginary passes in traffic when he is bombed, and smashing his body into parked cars on the mistaken impression that he is taking out the linebacker. Such a professional football player will feel like crying in the morning when he discovers his ribs are broken. I would feel like crying too. My pride, my substance, my capital, was to be found in my clarity of mind. . . |

” |

And yet Mailer brought himself back from these depths, and went on to accomplish more in his life and art than he had before this period of depression. That’s why he’s a model for all of us, writers or not: he has personal courage as well as talent.

I would have had a good deal easier life in academe if I’d specialized in one of the other authors in whose work I had an intense interest: Shakespeare, say, or Joan Didion, or Emily Dickinson. In 1965, when An American Dream was published, any critic could get a license for Mailer-bashing out of a vending machine on any street corner. When The Armies of the Night won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, An American Dream was suddenly declared a “contemporary classic,” not merely by its publisher, but by many literary people who had been reviling it and its author. Yet Mailer could still, as Jimmy Breslin said, “get into trouble in a phone booth.” When, in 1971, The Prisoner of Sex was published in Harpers (precipitating an editorial crisis which ultimately resulted in the resignations of the editor Willie Morris and much of his staff), Mailer again entered the realm of political incorrectness, which he’s never really left. The reason is that he’s fearless. He says and writes what he wants to, with no regard for consequences.

He was certainly growing larger in my consciousness. During the summer of 1963, I came very close to blows with an anti-semitic Mailer-reviler at a restaurant, although Mailer certainly didn’t need me to defend him. A few years later, after I had taught at the University of Texas at El Paso and become friendly with every bartender in Juarez, I found myself in Athens, Ohio writing a doctoral dissertation on Mailer. I wrote to him again. He remained silent. Prodded once more, he indicated that planned meetings never went well, and that we’d meet spontaneously one day and have a drink, after the dissertation was done.

Well, I tried. In the summer of 1967, I finished the dissertation, got into my Mustang at 3:00 AM, and drove to Provincetown to find him. Thirty-four years later, after writing The Structured Vision of Norman Mailer and innumerable articles and letters, and after many meetings with Mailer, I’m still finding him.

So in late summer 1967, I left Brooklyn at 3:00 AM to visit Mailer spontaneously. Some hours later, with the mid-morning sun beating on me and my adrenaline high wearing off, I pulled into the first gas station I saw, jumped out and started asking everybody, “Where’s Norman Mailer?” Most bystanders looked at me blankly. Finally, one of the station attendants asked, “You mean that crazy writer fellow from New York?” and told me to drive down Commercial Street until I saw a white Corvette with New York plates. I ran back to my car, only to see the car he’d described pulling into the Howard Johnson’s lot. It was jammed with kids, like a clown’s circus car, and I astutely noted that the driver wasn’t Mailer but a young woman, perhaps 18 years old. Conscious of the potential ironies of conclusion-jumping, I asked: “Do you happen to know the whereabouts of the famous writer, Norman Mailer?” Everybody laughed.

Reassured, I continued: “You’re his kids, right?”

“No, I’m his secretary. These are his kids.”

Mailer was away at a writers’ conference. So much for spontaneity. So I followed the group into the restaurant (this was before the advent of anti-stalking laws), ordered the cheapest thing on the menu (french fries) and learned that despite my perception of myself as the foremost fan and expert on Mailer, I was still a jerk to everyone else.

Well, here I was, in my self-styled role as the primary devotee of (if not authority on) Mailer’s works, and I’m told by this officious eighteen-year old woman, just out of her freshman year at Berkeley, whose job was babysitting and typing an occasional letter, that if I were to return on another occasion and approach the back door I might get a book signed. Not only that, but the advance copies of Why Are We in Vietnam? were in at the Provincetown bookstore. So I slipped away, spent my remaining gas and food money on a first edition of Vietnam (almost a decade between The Deer Park and American Dream, and now here’s another novel barely two years after Dream), drove back to Brooklyn (the last few miles on fumes) and wrote another chapter.

In early 1968, Mailer read excerpts from the forthcoming Armies of the Night at Wesleyan. By now the dissertation was finished; I was a Ph.D., living and teaching in Connecticut. I drove over to Wesleyan and as he walked down the aisle to the stage, handed him a copy of the manuscript. I could see him leafing through it as others spoke. After his reading, I stood at the periphery of a group of academic questioners, not too unobtrusive in my jeans and cowboy boots. Finally, he looked me full in the eyes and said,

“Do you have a question, or are you just gonna stand there?”

I didn’t want to give him a bag of shit; I just wanted to shake his hand. So I stepped forward and said, “I don’t want to give you a bag of shit. I just want to shake your hand.” He looked at me more penetratingly. “What’s your name?”

I told him.

“Did you write this?”

I admitted it.

“Let me borrow it for a month or so, okay? You seem to be the only guy who knows what I’m up to in An American Dream.”

Subsequently, Mailer sent the manuscript back with some gracious comments. Among other things, he wrote:

| “ | I . . . did think your stuff on The Naked and the Dead was the best and most interesting criticism that I’ve read on the book and in fact gave me the desire to go back and read it again. . . . And your stuff on An American Dream was generally very good. If the rest of the book is up to what I saw you’ve not only a good thesis, but an exciting career ahead as a critic if that should continue to interest you. (30 July 1968) | ” |

In 1970, we met briefly under similar circumstances, again at Wesleyan. By now I had expanded the dissertation and published The Structured Vision of Norman Mailer. I had married, fathered my first daughter, Brett Ashley (Buffy) Leeds, bought a house in the woods and refined my view of myself as iconoclast: the Jeremiah Johnson of academe.

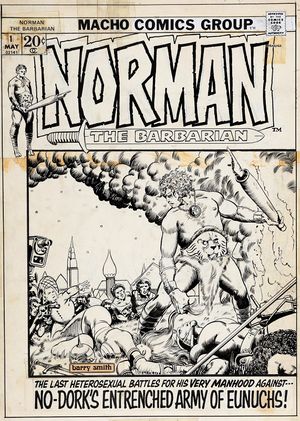

In the 1970s, satires of Mailer in the popular press had become quite broad. For example, the May 1972 issue of National Lampoon included a four-page comic book written by Sean Kelly and drawn by Barry Smith entitled Norman the Barbarian, in which a caricature of Mailer, dressed in a fur loincloth, armed with a pen and accompanied by a sidekick named Bress-Lin, fights the forces of women’s liberation amazons and conquers the Bitch-Goddess Media.

In 1972, the poet and translator Al Poulin called me from SUNY Brockport and told me that Mailer would be speaking in Rochester. He asked if I could arrange to have him drive over to Brockport where I could interview him on TV tape for the Brockport Writers Forum. I wrote Mailer a registered letter, and a few days later the phone rang. Robin, my wife, smiled and said, “Somebody named Norman wants to talk to you.”

“Hey, Barry,” he said, as though I’d seen him yesterday, “I’m in Boston. I’ll be in Rochester in two days. Here’s what we’ll do. You come to the lecture. Have a car outside. After the question period, we’ll drive over to Brockport, have a couple of drinks, and tape the interview. We should be able to do it in under two hours. Tell them to expect us about 2:00 AM.”

Was I excited? Yes. Did the SUNY guys come through? No. Too many problems with getting the studio at that hour, and other logistics. I called Mailer and told him their alternate offer: come next year, and they’d have a Mailer weekend: lecture, parties, a screening of Maidstone, and our interview. When I told Mailer, he said okay, but the spontaneous plan would’ve been better.

One last thing: “If we do it, there’s one condition.” I waited: what? Belly dancers? Irish coffee? Rocky and Bullwinkle as warmup?

“You’re the only guy I’ll do the interview with.” That was fine with me, but that gig didn’t come about. Al Poulin became seriously ill, and Mailer and I drifted out of even this tangential connection. It would be 1987 before I’d get to interview him (no TV), and in the same season I would be interviewed on TV for the Brockport Writers Forum by my friend, the poet Tony Piccione, largely about the work of Mailer and Kesey.

So we said goodbye on the phone. “Goodbye, Barry.”

I was so cool: “Goodbye, Nuh, Nuh, Nuh, NORMAN!”

More time passed. I went through my own creative crisis, wrote my own deservedly unpublished novel, and turned to the works of other novelists in my critical writings. I taught my twelve-hour load year after year, moved up to full professor, and most important, Robin and I had our second daughter, Leslie. In 1981, with my book on Ken Kesey about to be published, I was at an academic conference to speak on Kesey when Michael Lennon, a fellow Mailerian who was to become a good friend, introduced himself and asked why Norman never heard from me anymore? (You don’t write; you don’t call!) I was surprised: I’d never wanted to make my career by bothering any author, especially Mailer, who I knew guarded his time and privacy.

I wrote him again, we resumed our correspondence, and a series of gradually more personal meetings ensued. On November 8, 1982, he spoke at Yale. After his talk, I approached him. He greeted me warmly and invited me to a party at the apartment of Shelley Fisher Fishkin, then teaching and working on her dissertation at Yale. We had a fine, intense talk, then left for another party, accompanied by Robin and by Dominique Malaquais, the undergraduate daughter of Mailer’s friend, Jean Malaquais. We found ourselves wandering through the campus and streets of New Haven with glasses in our hands, talking. I remember quoting the wisdom of my maternal grandmother, and telling Norman what a great influence he’d had on my life. I still feel that way.

In September 1985, Mailer participated in a conference at Connecticut College in New London (formerly Connecticut College for Women), a potentially hostile setting. He was received well, both by his fellow panelists and the audience. Again, he was not merely articulate and forceful, but charming and amiable to me.

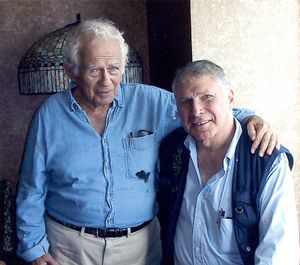

It was a tough decision for me in 1987, but I decided to undertake another book on Mailer rather than break new ground on Harry Crews or D. Keith Mano or Joseph Wambaugh. I wrote him, asking for an interview. He responded with characteristic grace and generosity, and after several postponements for more important events in his life, notably a trip to Russia, he decided that we should do it right away. I won’t be coy and pretend this wasn’t a major experience for me. There I was, in the place where he wrote the books that had so dramatically informed my life’s vision, talking intensely with Norman for a morning that went by far too fast. You can read the official transcript of it between these covers.

At the first International Hemingway Conference, held at the John F. Kennedy library in Boston in 1990, Mailer was the keynote speaker. After his talk, I approached to say hello. He was seated next to Jackie Onassis, who held out her hand as if to have her ring kissed. Norman had turned to say something to his wife Norris.

“I’m happy to meet you, Mrs. Onassis,” I said, shaking her hand briefly, “but I’m actually here to see Norman.” She seemed startled at my preference; but no Secret Service agents roughed me up, and Mailer turned and greeted me warmly.

When I wrote Norman in 1992, he gave me his Provincetown phone number. I called him from the Provincetown Inn, and he invited Robin and me to dinner at Sal’s Place with him and his daughter Maggie, who was an undergraduate at Columbia. We had a great time eating, drinking wine, and talking non-stop. Afterwards, we sat around with Jack, the massive-forearmed proprietor, and talked about the old days in Provincetown. I was being good, and resisted the impulse to ask Jack to arm-wrestle. Later, Mailer wrote me: “I still remember the look in your eye when you restrained yourself from asking Jack, the proprietor, to arm-wrestle with you. If I ever had any doubt of the ferocity you contain and have managed to domicile in yourself, it was removed at that point. What a display of character over physical greed and desire.” (28 October 1992).

Norman was in a good mood, having finished his book on Picasso that day. After dinner, he drove us all over Provincetown and its environs, pointing out places we should see in daylight, and apologizing for not arranging to go with us the next day. He had to begin editing the Picasso manuscript. At our hotel, Norman got out to say goodbye. We hugged each other, and he said, “See you soon, buddy.”

When I got back home, I had occasion to reread Tough Guys Don’t Dance and screen the movie version for an article I was writing. It was a pleasant jolt to read about and then view the places we’d just been together.

In 1995, I had the fine experience of having dinner at Norman and Norris’s house on Commercial Street, with Robin and Norris, Maggie and my artist/writer/poet daughter Leslie, who had recently graduated from Connecticut College. After dinner, while our wives and daughters chatted, Norman and I sat up late in his bar overlooking the ocean drinking single malt scotch.

When we ran out of time and energy but not talk, and had exhausted the patience of the women, he suggested we meet for breakfast at Michael Shay’s restaurant, which has since become one of my favorite Provincetown haunts. I remember that the Mark Fuhrman controversy had just reached its peak in the news that morning, and I suggested that Norman eventually write something on the O. J. Simpson case. Although he felt the subject was virtually mined out, he did finally write the screenplay for a mini-series years later.

In the years since, I have had a recurrent and gathering gratitude that we are unable to see our futures. The last five years of the decade and the century brought great tragedy and travail, as well as new achievement and triumph for me.

When my beloved daughter Leslie died suddenly in 1996, I had no reason or intention to trouble Norman with my personal life, so I didn’t write him of this. But my good friend Mike Lennon interceded: when I wrote Michael of Leslie’s death, he immediately informed Norman. A day later, an envelope covered with stamps arrived Special Delivery. In it, Norman sent a beautiful, poetic, heartfelt letter of condolence and commiseration. That letter will remain always in a secret compartment of my heart.

Where can I start to write about Leslie? How can it be other than a series of clichés, like those of any other bereaved father? All I can say is that I miss her terribly, profoundly, irrevocably.

The funeral director, a character out of Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One, didn’t believe the bereaved parents and sister could arrange and speak at the funeral, so he had a minister waiting in the wings. I had my friend Bob Miles standing by to finish my eulogy in case I became unable to continue. But we did it. We made a pact that we would not only try not to break down during our own speeches, but during one another’s, so that we wouldn’t set off a chain reaction of uncontrollable, wracking tears. Throughout the assembled, there were audible sobs, even among the tough Motor Vehicle guys Robin worked with. But we did it. Here’s what I said:

| “ | When Leslie was born, after a predawn drive to the hospital on black ice in a vicious February, she ameliorated everything by the radiance of her smile. That face, that Leslie smile, would melt this snow outside and the ice that encases my heart, our hearts, today. Her literary and artistic accomplishments merely echoed the intensity and beauty of her intuitive center, as her lovely face was but an image of her beautiful soul. I won’t see her like again. | ” |

My Leslie was a mass of engaging, often frustrating, contradictions. Painfully shy in childhood, she was also furiously independent, as when at age two she refused for hours to wear a winter coat in the coldest weather, never admitting to discomfort. She wanted approval; but when she went to receive her Winthrop fellowship (conferring early selection to Phi Beta Kappa), she wore a black leather jacket to the reception. Her response to the dirty looks she got from officials was, “Fuck them. I got the grades!”

That was Leslie. That is Leslie, because she’s here in me, and will be until I die. But the world will never be the same again. I don’t know why she had to leave us. But as Millay, one of her favorite poets, wrote, “I only know that summer sang in me/ A little while, that in me sings no more.”

At the cemetery, we lay Leslie in the frozen ground. Our friend Ross Baiera read one of her favorite Edna St. Vincent Millay poems, ending with “But you were more than young and sweet and fair/and the long year remembers you,” and then led us in the psalm of David. Everyone waited for a cue as to what they should do next.

“Goodbye, Leslie,” I said. What more was there to say? Everything. Nothing. And we left. I’m still trying to say goodbye. I know I never will.

And now? Now? I still have days when I wander through the empty house, blinded by tears, calling her name aloud. I haven’t lost my sanity, just my heart. Nonetheless, I try to remake my new life, a life without Leslie. What life is that? Well, there’s one out there, I suppose. Or in here.

I see now that I’m not just badly bruised like Rocky Balboa after his first fight with Apollo Creed. Something’s broken inside me that will never heal. Just as Crohn’s Disease is not the 24 hour flu or a mere irritable bowel, my condition is chronic, permanent. There may be remissions, but no physician exists who can cure me.

The summer of 1996 found us in no mood to return to Provincetown. Instead, Robin and Buffy and I took a trip to Newport, where we began to understand the statistical dictum that the vast majority of marriages in which a child dies end in divorce. When, in 1997, Robin showed little or no interest in accompanying me to visit the Mailers, I went alone.

By the summer of 1998, with our marriage sadly eroded after more than thirty years, Robin and I separated. On this visit, which had begun to be an annual event, I was accompanied by my long-time friend Beth, with whom friendship had ripened into something more.

During the fall semester of 1998, teaching my Course titled Norman Mailer: Fifty Years of Achievement, I was so impressed by the intense engagement of my students with Norman’s work, and the high quality of their midterm exams, that I called him to ask if we could make a group pilgrimage to visit him. Instead, he made me an even better offer: he came to my class, secretly, to avoid crowds. These students were volunteers, not draftees, and it was they and they alone who deserved to benefit from and enjoy his visit. Beth and I picked Norman up at the train station in Hartford, slipped him in and out of my office and my classroom like Zorro or the Scarlet Pimpernel, and had a fine, stimulating discussion with my students, which Norman repeatedly said he enjoyed as well. Beth and I took him to dinner, dropped him off at Wesleyan where we hooked up with much of his family, including Norris, his sister Barbara, and most of his “kids,” and declined their invitation to attend the play in which Norris and Norman’s youngest son, John Buffalo, was featured. Instead, we kept our promise to meet my students at Tony’s Central Pizza, across the street from the CCSU campus, where we found them amidst a forest of beer bottles and pizza crusts, still avidly debriefing each other.

The pilgrimage idea did not, however, die. In October 1999, I took a group of graduate students from my Mailer/Kesey seminar to Provincetown to meet Mailer and have a three hour seminar in his living room. They were so grateful, excited, dazzled to the point of awe, and so intelligent in their questions, that I realized the experience was analogous to how I would have felt if one of my professors had taken my class to Key West to visit Hemingway at his home. I was very proud of them, and very grateful to Norman. The year 2000 brought another fine visit. By now, Beth and I had decided that autumn visits were preferable to summer. That fall, despite Norris’s cancer (and the consequent surgery, chemotherapy and radiation) and Norman’s painful arthritis, they were not merely stoical and self-deprecating about their own travails, but, as always, warm hosts. Over cold vodka and sushi, followed by hearty Russian borscht, we had the pleasure of discussing Norris’s fine first novel, Windchill Summer, (of which I write in Chapter 10) and of having two Mailers sign their books for us.

That’s only one example of why it’s so exciting to work on an author who’s still alive and active. It’s a dynamic adventure of constant revelation. Most of us who choose to teach literature have embarked on a voyage of self-discovery, seeking to explain ourselves. I’ve found myself; but I’m still in the process of finding Mailer.